Protecting farmland benefits us all

In these fraught and divisive times, it is heartening to see grassroots democracy working well for the good of the people now and in the future.

We came across a stellar example at the most recent Knox Town Board meeting. The four council members — a farmer, a mechanic, a grandmother, and a small-business owner — were all elected with Republican backing. The supervisor, formerly the town’s assessor, is a Democrat.

Refreshingly, the topic at hand — farmland protection — had nothing to do with politics. The board members listened attentively, asked reasonable questions, and got informed answers as Gary Kleppel presented a plan to protect the one third of land in Knox that is used for agriculture.

Kleppel, a sheep farmer and professor emeritus who heads the town’s agriculture committee, said his committee has drafted an application to get a $25,000 grant from the state’s Department of Agricultural and Markets.

“We are just the instrument for preparing proposals for the town,” Kleppel told us of his committee. “The elected representatives of the people have to submit the proposal in the name of the town.”

If the application is approved and funded by the state, Kleppel said, three partners will help work on the plan: American Farmland Trust, Cornell Cooperative Extension, and the Albany County Soil and Water Conservation District.

The seed for the project was planted in 2024 by Angelica Stewart when she came to a meeting of the agriculture committee. She and her husband have a small farm on Craven Road, Kleppel said.

Although Kleppel did not want to share a draft of the plan with The Enterprise until after the town board has had a chance to review and revise it, he told us how different it is from the usual farmland protection plans that various municipalities have adopted.

Those plans lock the farmland down by removing development rights.

“The focus of our proposal,” Kleppel said, “will be to secure and improve the livelihoods of farmers, to make farm families and farm livelihoods more economically and environmentally secure.”

If a business is doing well, Kleppel stressed, the business owner doesn’t sell it.

How will the town go about improving the livelihood of farmers?

Kleppel envisions surveys and sessions where farmers can “come and talk about what keeps them up at night,” he said.

“For me, it might be that the water in my well has gone dry. Other farmers might be kept up at night because they can’t get access to certain equipment — it just isn’t around.”

He summarized, “Whatever things are on farmers’ minds, we want to know about them.”

What Kleppel said next struck us as a model anyone in government or involved in policy making should heed.

“When you know the problem, then you can solve it,” said Kleppel, adding, “Or at least you can decide whether it’s solvable.”

Kleppel thinks, for example, the karst topography in the Helderbergs affects more than just farmers. The thin layer of soil over the limestone means most Hilltown farmers don’t raise vegetables but rather focus on protein like meat or milk or eggs, he said.

The karst topography resulted from the limestone bedrock being dissolved by rain or groundwater causing caves and sinkholes and disappearing streams. It’s a fragile ecosystem.

“Our water supplies are sensitive — that is something that not only farmers but everybody in town has to be concerned about,” said Kleppel.

He believes it’s important that elected representatives at the county and state know about karst topography. “You’d be surprised how little is known about that in the government,” he said.

Another part of the proposal is to identify ways farmers deal with decisions they have to make about their property. For example, a farmer might need cash to deal with a family issue. “We’re not going to restrict the farmer from selling his or her property,” said Kleppel.

Rather, the plan is to offer a dozen different options the farmer might explore in lieu of development.

One example would be to use local farmland funds to help the farmer in need sell to a young farmer who doesn’t have much cash but who would be able to pay back once his farm was established.

Knox, as throughout the Northeast, was once dotted with dairy farms.

“Small-scale dairy has been part of agriculture in the Northeast since the first cow landed in America,”

said Kleppel.

The town’s last dairy farm, the Gade farm, closed on June 2. “From 1974 to June 2025,” said Kleppel of the last half-century, “we went from 35 dairies to zero. And I can tell you nothing gets me more pissed off.”

Why?

“That’s part of who we are,” he said. “That’s our culture.”

When he was just 6 years old, Kleppel said, “I knew the name of the farmer who delivered milk and eggs to our house … and put those bottles in the little tin box we kept on our porch and took the old bottles away.”

He went on with his reminiscence of those halcyon days, “When I was a little boy, my friends and I, if we rode down to the dairy at the bottom of the hill near our homes and stood at the loading dock, somebody would come out with cream sticks for us …

“And to see it disappear because a few mega corporations want to concentrate all the milk into a few farms is nonsense.”

But is it possible to revive a bygone way of life?

Kleppel believes it is. He has visited successful small dairies in Vermont and “up and down the Hudson Valley.”

If farmers have access to pasteurization equipment, he said, “they’re able to manage 250 and fewer cows and make not a good living but a great living.”

These small-dairy farmers succeed, Kleppel said, because they can pasteurize their own milk and because they offer a variety of products like cheese and ice cream or chocolate milk and skim milk.

Kleppel is planning a gathering of local state representatives, including Senator Patricia Fahy and Assemblyman Chris Dague, a former dairy farmer, in February — which is when farmers have the most time — to meet with experts, his committee, and local farmers to discuss options for pasteurization.

“We need a good economist to find out what the feasibility of small-scale pateurization is … even the state might want to invest,” he said.

“It would represent an investment in small-scale agriculture, which ultimately will lead, we hope, to turning the concept of the mega farm back into the family farm. What we really care about is securing the livelihoods of our farmers.”

If Knox is successful in securing the grant, rural planner Nan Stozenburg, formerly a farmer herself, “would take the lead in data collection, mapping, workshops … to develop a tractable plan, one that we can use,” said Kleppel.

Roughly 150 Knox residents, 6 percent of the town’s population, are farmers, he said.

“That doesn’t sound very high but remember that 1 percent of the people in the United States of America are farmers. So we have six times more farmers than the average."

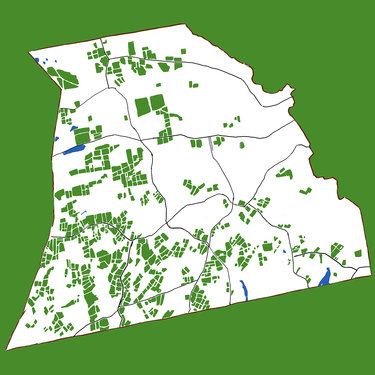

Also, while many landowners are not farmers themselves, they lease their land to farmers for, say, grazing or haying. Knox Supervisor Russell Pokorny said that there are 1,500 agricultural exemptions in town as 33 percent of the land is farmed.

“We are an agricultural community,” said Kleppel. “Agriculture is our economic engine.”

We urge the Knox Town Board to forward the proposal to the state and urge the Department of Agriculture and Markets to fund the study.

This could serve as a model for many communities as sprawl gobbles up acres of farmland.

Other than the beauty that farmland provides all of us, it uses little tax money compared to residences and businesses that need services like schools and sewer systems.

All of us need to eat. And buying from local farmers not only enhances our local economies but prevents the need for climate-changing transportation of farm produce from far-flung places.

We believe this plan shows government at its best, working not for the benefit and power of large corporations, but for the good of the people.