State botanist unravels a 200-year-old mystery

James Lendemer sought a picture of old lichen specimens for a book, and discovered a lost grail.

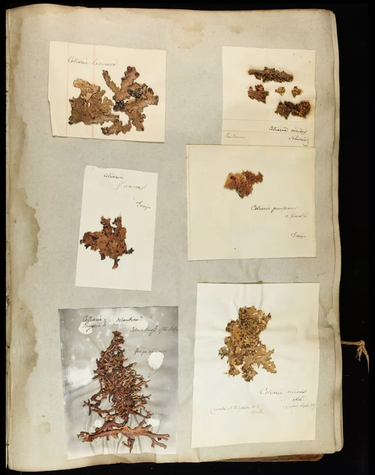

In a box in a cabinet of the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, he found a time-worn book that he identified as Abraham Halsey’s lost lichen collection.

Lendemer, the curator of botany for the New York State Museum, told his carefully researched journey of that book at a talk last November for the Torrey Botanical Society.

His paper is in the December issue of the Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society.

“It’s a truly remarkable story, two centuries in the making,” said Lendemer.

He mapped travels of the 1823 collection through New York City and through time.

Describing Halsey as a “forgotten botanical pioneer,” Lendemer said, “We don’t even know what he looked like.”

Researching old court records, Lendemer learned that Halsey was deemed an “insolvent debtor” in 1821, although he came from an established family; his father was a silversmith.

He owed the equivalent of $162,000 today. A catalogue of all of his household possessions listed every spoon and every teacup but did not include his foundational collection.

At the same time he was dealing with insolvency, Halsey was attending New York City Lyceum meetings, taking notes as its secretary.

It was thought that his 1823 collection burned in an 1866 fire.

Lendemer is restoring Halsey’s reputation from being “reduced to a footnote” to actually being a botanical pioneer with a foundational collection.

Halsey’s long-lost collection of lichen within a 50-mile radius of New York City lets scientists understand the area’s pre-industrial lichen communities.

His 1823 checklist documents 129 lichen species. By the 1960s, Lendemer said, lichens were “completely eliminated” due to pollution.

“Lichens are symbiotic fungi,” said Lendemer and are “essential to understanding how life on Ear has changed and is changing.”

In 2020, after the city’s air had been cleaned considerably, Jessica Allen documented 94 species of lichen in New York City, Lendemer said.

But just a handful of them were the same as those catalogued by Halsey, highlighting how the natural landscape has been transformed into a human landscape where biodiversity has to evolve to survive.

Lendemer wrote in his paper that his study “highlights the value of natural history collections in reconstructing historical ecosystems, contextualizing centuries of human-mediated environmental change, and informing conservation.”

He concluded his talk to the Torrey Botanical Society by stressing the importance of digitizing the various collections of lichen. “Imagine the discovery that would be possible when all of it’s done,” he said.

His paper concludes, “Importantly, archival records newly reported on here unequivocally dispute the historical narrative that the herbarium of the New York Lyceum was destroyed by fire and instead suggest it survived in the Mercantile Library Association at Astor Place in Manhattan.

“The present-day whereabouts of this invaluable herbarium are unknown, and it is likely unnoticed and unrecognized in an institutional library or archive somewhere in the New York City metropolitan region.”

The search goes on.