Suburbs attract families from abroad, students at GCSD speak 53 languages

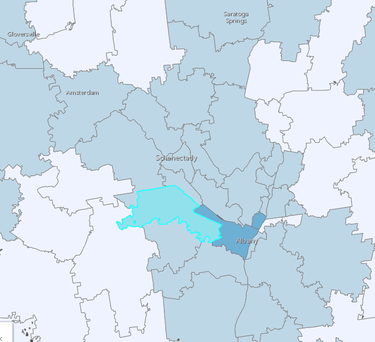

— Map from Office of the New York State Comptroller

Enrollment rates for English language learners: The Guilderland school district, with 5.3 percent ELL enrollment, highlighted in turquoise, is next to the Albany school district, in darker blue, with 13.61 percent ELL enrollment; other suburban districts, in light blue with up to 10 percent ELL enrollment; and districts colored white, indicating 0 percent ELL enrollment.

GUILDERLAND — Students who come with their families to New York state from other countries are increasingly settling in suburbs.

The number of English Language Learners, called ELLs by educators, outside of New York City has increased by 8 percent from the 2019-20 school year to 2022-23, according to an audit released last month by the state comptroller’s office.

The audit, which focused on city districts, also mapped all school districts in the state for the percentage of English language learners among enrolled students.

In Albany County, as statewide, rural districts have very few ELLs. Berne-Knox-Westerlo is listed at 0 percent. Voorheesville, serving a once rural area that is rapidly turning suburban, is listed at 1.14 percent.

City districts generally have the highest concentration, with Albany at 13.61 percent.

Suburban districts typically fall in between with Bethlehem, for example, at 1.25 percent.

Guilderland, at 5.3 percent, is among the highest for a suburban district in the area along with South Colonie at 5.1 percent and North Colonie at 5.56 percent.

In 2017, when new state regulations went into effect, the late Demian Singleton, who was Guilderland’s assistant superintendent for instruction, said that, over the past four or five years, the number of new English learners in the district had increased 400 percent.

According to Rachel Anderson, Guilderland’s current assistant superintendent for instruction, the district in 2024 has 258 students who are receiving ENL — English as a new language — services.

Together, these students speak a total of 53 different languages, according to Lauren Anderson, the administrator for World Languages and English as a New Language for the Guilderland schools who is not related to Rachel Anderson.

The comptroller’s report lists some of those languages spoken by Guilderland students as Hindi, Turkish, Urdu, Spanish, Chinese, Telugu, Maylayalum, and Chuukese.

The comptroller’s audit found that, as of August 2022, the four-year dropout rate for ELLs was 16 percent, notably higher than the average overall dropout rate statewide of 5 percent.

Last year, 95 percent of Guilderland students graduated, according to the State Education Department. In 2016, Guilderland had 75 percent of its ELLs graduate at a time when the statewide average was 31 percent.

Asked about the current graduation rate of ELL students at Guilderland, Lauren Anderson emailed The Enterprise, “Last year we only had 4 students that were ELLs in their senior year. Our multilingual learners are represented in our overall graduation rate — these are students who speak multiple languages, some of whom tested out of the ENL.”

Seema Rivera, who left her post as the president of the Guilderland School Board earlier this year when she was appointed to the Board of Regent, the body governing education in New York state, told The Enterprise that, when she graduated from Guilderland in 1997, the district was not nearly as diverse as it is today.

Rivera, who is of Indian descent, was a strong proponent for diversity, equity, and inclusion in Guilderland as the board created the post of DEI director and Rivera served on the board’s DEI Committee.

While the state has done a good job with standards that are culturally responsible, Rivera said, and while DEI has long been a focus in urban schools, “Suburban schools are becoming a lot more diverse. I don’t think a lot of people realize that,” she said.

Guilderland is “nowhere near the threshold” where the state would require bilingual education, Rachel Anderson said. That threshold is reached if there are 20 or more English language learners in a similar grade level who speak the same language.

The comptroller’s report focused on schools where that is required and concluded that the State Education Department needs to improve its oversight of the required services for students learning English.

At Guilderland, however, the ELLs are stretched across many different grades with dozens of different languages.

So, rather than having bilingual classes, the teachers either “push in” to a regular classroom where they co-teach with the content teacher or “pull out” ELL students to work in small groups, Rachel Anderson said.

She said that “inclusive teaching strategies” used throughout the district — for example, with special education students — benefit all students. With the ELLs, she said “You have this other cultural phenomenon going on right in their presence.”

There are 14 ENL teachers at the elementary level, Rachel Anderson said. “That is by far our largest teacher population,” she said, “because we’re spread across five buildings.” The five elementary schools also have more ELLs.

At the high school, there are just three ENL teachers as many students have exited the program, having gained command of the English language.

Each year, ELL students take the New York State English as a Second Language Achievement Test that determines the services they will receive.

Translanguaging

Lauren Anderson, who has chaired World Languages at Guilderland for a year, had taught French at Guilderland High School for nine years before that.

She majored in French at Le Moyne College and her study abroad in Paris set her course for life, she said.

While she always knew she was interested in teaching, Anderson said, it was the international travel and “learning about other cultures” that sealed the deal.

Guilderland, she said, uses a “translanguage” approach to teaching students from other countries. For example, if a student is a native French speaker, “let them think in French” but the end product of their thinking is to be in English.

“Our goal is to promote the English language,” she said.

The instructional strategy is considered a scaffold, she said. The sentence provides a frame for students to start.

Visual clues and gestures are used to help with communication. Cognates or words that are similar, coming from the same route, are also used to further understanding along with graphics.

While the comptroller’s report said there is a shortage of teachers and recommended increasing the pool of certified ENL teachers, Anderson acknowledged the statewide shortage but said, “All of our positions are filled with certified teachers.”

Asked how the district managed to fill all of its posts in the midst of a shortage, Anderson said, “Our model of instruction is really solid. Teachers enjoy working in Guilderland.”

The comptroller’s report also recommended that the State Education Department “enable efficient sharing of information between school districts to ensure continuity of services for ELLs who relocate.”

Both Rachel Anderson and Lauren Anderson said Guilderland frequently shares best practices with other districts and also offers professional development for its teachers.

“Lauren herself and many of our teachers participate in some professional development programs through Capital Region BOCES and … the Regional Bilingual Education Resource Network,” said Rachel Anderson.

Lauren Anderson said, though, that a better statewide system is needed for sharing student data. She said of the annual English as a Second Language Achievement Test, “We can’t give the exam again” and “we need to know how many service minutes based on the previous score.”

Too often, there is a delay in getting that information when a student transfers, Lauren Anderson said, adding, “It would be great to have a shared database.”

Guilderland’s focus, Lauren Anderson said, is to help students progress to the grade level with their peers.”

If an English language learner comes to Guilderland in elementary school, she said, it takes four years on average for that student to reach grade level. “If a student comes later, it might take longer,” she said.

She also said that the student’s first language makes a difference in the ease of transition; for example, it’s easier if that first language is an alphabetic language. Another difference is the level of education the student had in his or her native language.

The state sets out five levels for students to progress through: entering, emerging, transitioning, expanding, commanding.

“Generally, we can see them move to emerging from entering in a year,” said Lauren Anderson.

After a student has tested out at the “commanding” level, he or she is eligible to receive service for another two years.

“It’s really wonderful in August when I get the report on tests,” said Lauren Anderson, speaking of the joy of sharing those scores with the teachers.

Beyond the classroom

The district also provides translation services to help families who do not speak English. While many Guilderland students become translators for their families, “That’s a lot for a kid,” Lauren Anderson said.

“Last year,” Anderson said proudly, “we had our first ELL earn the Seal of Biliteracy.” The state program entails demonstrating English and world language proficiency through exams, coursework, and a research presentation.

“Teachers definitely try to establish relationships with families,” said Rachel Anderson of the ENL teachers. “Part of our ENL program is family outreach and making sure that we’re making those connections with families because we know that it’s important for students to feel comfortable in the classroom and in the schools.

“And it’s also important for families to feel comfortable working with us and reaching out for resources and knowing that this is a community that welcomes them.”

Rachel Anderson also said, “I think teaching in general can be kind of an isolating profession because you are in your classroom, working with students, and sometimes it’s difficult to really get that time to work with other adults to reflect on your practice and to share ideas. So we try to make space for that as much as we can.”

She explained, “Teachers are encouraged to plan and reflect together and we try to also make time in department meetings and professional development settings to have those conversations and allow teachers time to connect with each other.”

Asked why Guilderland had a higher percentage of ELLs than many comparable districts, Rachel Anderson said, “I’m really not sure I can even speculate on that … But our philosophy here is that our responsibility is to educate all the students that are in our community. We have a certain number of students in our community who are ELLs and who are learning English and we’re supporting them to the best of our ability.

“Part of what we’re trying to do is make sure that all of our families and all of our students feel that they have a place in our community and that they’re welcome here.”

She described the annual end-of-the-year celebration were the families of English language learners come together to share a meal with each family contributing food from their own culture.

“This past year, there were students who did some performances and their student work is on display,” said Rachel Anderson.

The event is hosted by Lauren Anderson and the ENL teachers.

“It is a beautiful event … it is just amazing,” said Rachel Anderson. “It’s inspiring because you see all these families come together from all different backgrounds and cultures and they’re sharing their cultures.”

She concluded about the large number of ELLs at Guilderland, “I would love to say it’s because we have an outstanding educational program. Is that the truth? I don’t know.”