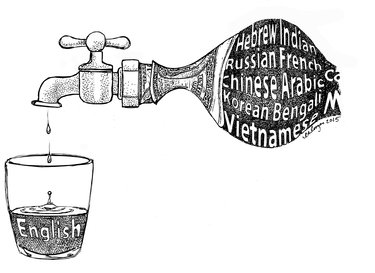

Unneeded state requirements can shut down the flow of learning

Sometimes reality and idealism clash. That is happening right now across New York State for students who have come from other countries and are now learning English in public schools.

A top-down directive from the State Education Department instructs schools on how they must staff their programs to teach what the state now terms ENL — English as a New Language — students.

Who would argue with the value of teaching newcomers to this country to speak its language? It is essential for the students to succeed in their new home and, in the long run, the success of these students enriches our society as a whole.

The ideal is costly. The new regulations adopted last summer by the Board of Regents will require students to receive both “pull-out” and “push-in” services during English instruction. That means teachers are to visit English learners in their home classrooms as well as working with them outside of the classrooms. Additionally, if there are more than 20 students across a district who speak a single foreign language, the district is to hire a bilingual teacher for them.

Looking at how this affects just one district — the Guilderland central schools — is instructive. The suburban Guilderland district is third in the region, behind the city districts in Albany and Schenectady, for its number of ENL students.

Right now, Guilderland has about 230 students who are learning to speak English, a number that has grown 200 percent in the last eight years. The district’s current program serves students who speak 33 different languages, including Chinese, Korean, many Indian dialects, Turkish, Russian, Arabic, French, Bengali, Vietnamese, and Hebrew. More than 20 Guilderland students speak Mandarin Chinese and perhaps as many as 20 speak an Indian dialect.

The superintendent, Marie Wiles, has calculated that, even if no foreign students moved to Guilderland next year, which is unlikely given the current trend, the district would have to hire 7.4 teachers at a cost of $577,200 to meet the new state requirements, which she notes is nearly 1 percent of the district’s tax levy. She has also pointed out that qualified ESL — English as a Second Language — teachers are in short supply. The same is true of Mandarin Chinese teachers.

When we asked the State Education Department if there are enough qualified teachers to meet the mandate, we got this reply: “The Department continues to be committed to the recruitment and certification of new bilingual/ENL teachers, in an effort to address the increasing shortages in several regions of the state.”

In short, the reality is there are not enough teachers to meet the mandate.

There is a financial reality, too. Guilderland, typical of many districts, is tapped out. Guilderland has stayed under the state-set tax-levy cap since it was implemented out of caution it couldn’t muster the supermajority vote needed to surpass it as well as out of consideration for taxpayers. With decreased state aid, to close multi-million-dollar budget gaps, the district has cut 227.6 posts since 2009 and the educational richness that went with them.

Meeting the new ENL requirements would mean taking away something else. After a recent forum for citizens on next year’s budget, the superintendent summed up the response this way: “The theme we heard was ‘Don’t cut anything.’ I understand that, because it’s been year after year after year.” Wiles said of the response to the 20-page list, “Not a single reduction in here is palatable.”

She also said, “We’re so far down...it is dire...We’re reaching into the metaphorical couch cushions, looking for change.”

When The Enterprise asked the State Education Department if there would be penalties for districts who didn’t meet the new requirements by Sept. 15, this was the reply we got: “All school districts are expected to follow all Commissioner’s regulations and take appropriate action.”

But what if they can’t? It seems like the answer sidesteps the question, implying there are no penalties.

So should districts ignore failing ESL students? Certainly not. That would only penalize the students.

The answer lies in looking more closely at the reality. Assessing needs on a district-by-district basis makes more sense in this case — a bottom-up rather than a top-down approach. What we’ve observed on the ground in Guilderland is a program that is working well with new staff being hired as needs arise.

We first became vividly aware of what was then called the ESL program seven years go through the words of Karem Ullah. He was 16 when we met him and one of just several dozen ESL students at Guilderland.

He had left his war-torn native Afghanistan when he was too young to remember and moved with his family to Pakistan. “My father died in 2005,” he told us. His father had returned to Afghanistan. “A person died, so he went to the mosque to share with the relatives,” Ullah said. His father was killed there by a bomb blast.

At 15, Ullah came to America and lived with his mother and siblings in Guilderland. Inspired by his ESL teacher, Susan Lafond, Ullah wrote a prize-winning essay, which he read to a gathering of Wounded Warriors. Ullah told the soldiers about themselves: “They always live in the dark to keep others in the light.” He was given a standing ovation that gave his teacher goose bumps.

Yes, she was there. Ullah’s brothers couldn’t get time off from work to take him to the Crowne Plaza in Albany; she wouldn’t let him miss it and took him herself.

Ullah told us how he missed his friends in Pakistan and how his ESL classroom— with its students from China, Korea, Poland, and Ecuador — was like a second home to him. Lafonde had been to his real home, too. She came during Ramadan with cake to eat after sundown. She doesn’t speak Pashtu and Ullah’s mother didn’t speak English. Lafond said, “We didn’t know a word the other was saying, but we understood each other.”

Lafond visited the homes of many of her students, helping where she could. “Sometimes, they have nothing, really no furniture,” she said. “Sometimes they have not applied for free- or reduced-[price] lunches. They’re grateful and don’t want to make waves.”

Often, the students had to translate for their parents who spoke no English. She used “a lot of acting, song, and dance” in her classes, Lafond said, to reach students who spoke many different languages and had varying levels of education. Those exceptional efforts and the learning that comes with it have continued at Guilderland.

In 2013, Marcia Ranieri, who currently heads the program, surveyed the ESL students, their parents, and graduates of the program and found near universal satisfaction. The elementary students were to circle either smiling or frowning faces, which overwhelmingly showed they liked the program and their teachers helped them with reading and writing as well as listening to them and making them feel safe.

Middle and high school students were also positive, writing comments as well. “Whenever I have a problem with anything, I get the solution from [my teacher]. She is the person who can make me happy in any situation. I am in my element when I am with her.”

Fifty-six of the 58 parents who answered the survey said the ESL program helped their children; two answered that they didn’t know. All said their children’s English skills were better because of the program.

Twenty-five of the 26 surveyed graduates of the program said they liked ESL; 18 of them are currently at a four-year college with three at two-year colleges. “ESL made me feel comfortable living in America and going to an American school,” wrote one graduate. “The ESL teacher was also kind and generous so she made me happy to go to an American school.”

“My time in ESL let me touch English, feel English, and think in English,” wrote another. A third, who spent two years in the program, wrote, “It was the most important and beautiful memory I had in my life in America.”

Ranieri informed the board at that time of both the “push-in” and “pull-out” instruction that was ongoing and requested more “push-in services.” She also requested an ESL specialist in reading be hired to help first-grade students who are struggling. The district complied in drafting its next budget, despite the tough times.

In other words, on its own, the Guilderland district was working to meet the needs of its students learning English. And Guilderland’s current $93 million budget draft for next year includes three new ESL teachers, one at the elementary level, one at the middle school, and 1.2 at the high school. That will cost close to $250,000. But it is far less than the 7.4 teachers for $577,200 the state is requiring. We back the good-faith effort.

But further, we urge an approach fostered by an earlier education commissioner that saw shared decision-making teams in every school so that districts didn’t have to walk in lock step across the state.

In response to some of our questions, the State Education Department said that currently the graduation rate for English language learners is 31 percent “and all districts must pool their efforts in order to ensure a better success rate for this population.”

Certainly, a graduation rate of 31 percent is unacceptable. But the requirements should be applied to the schools that need them. The education system in New York is ostensibly one of home rule, with elected school boards governing. Forcing all schools into the same mold is not only a waste of taxpayers’ money, it is not the best way to help students.

The real ideal would be to tailor the programs of each district to its students needs.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer