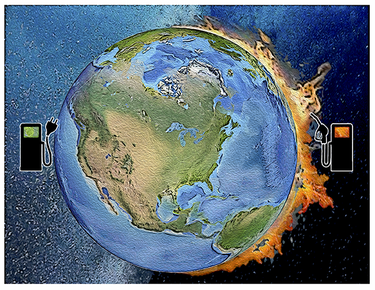

Charge your car as if the world’s future depended on it

A clear vision for a sustainable future is essential. But making any vision a reality involves charting a path, a reasonable way to get there.

We have, over years on this page, wholeheartedly endorsed New York’s landmark climate law, passed four years ago, calling for a transition to renewable, emissions-free sources of energy such as solar, wind, and hydro power.

As the ravages of climate change — from floods to fires, from droughts to storms — become more apparent, the pace faster than scientists had predicted, we see the harm to people around our globe, often to those least able to endure.

This should increase our commitment to the efforts our state has already initiated.

New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act mandates a goal of a zero-emission electricity sector by 2040, including 70 percent renewable energy generation by 2030, and to reach economy-wide carbon neutrality.

The scoping plan outlines actions needed for New York to achieve 70 percent renewable energy by 2030; 100 percent zero-emission electricity by 2040; a 40-percent reduction in statewide greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2030, an 85-percent reduction from 1990 levels by 2050; and net-zero emissions statewide by 2050.

So far, so good. But for the state to reach those goals, consumers need to buy in. Let’s look at just one sector to see where problems are arising: transportation.

Transportation in New York generates 29 percent of the state’s greenhouse-gas emissions, second only to buildings, according to a 2022 report from the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

Part of the needed change from gasoline-powered to electric-powered vehicles — hydrogen is not yet a realistic option — will fall to private companies like those in the trucking business. Other parts will fall to public entities like schools with their myriad buses or to municipalities that run public transportation.

Schools, for example, have a state requirement that new buses be electric starting in 2027, just a short four years away, and by 2035, all school buses must be zero-emissions.

A handful of districts, including Bethlehem locally, that have started the process have learned that electric buses can cost two to three times what a diesel-fueled bus costs, that high-speed vehicle chargers can cost $40,000 apiece, and that bus facilities may have to be expanded or at lease rewired to accommodate the charging stations. Also, there can be long waits to purchase electric buses.

While there is expected to be some offset in reduced fuel and maintenance costs with the new buses, school districts, and the public that must support their budgets, can expect steep cost increases in the years ahead.

Last week, Governor Kathy Hochul’s office put out an upbeat press release announcing $100 million will be made available statewide for zero-emission school buses in the first round of funding under the $4.2 billion Clean Water, Clean Air, and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act of 2022.

“Zero-emission buses will become a hallmark,” said the governor in the release, “not only transporting students through our communities, but also demonstrating the promise and possibility of a healthier, environmentally friendly, low-carbon future for our youngest citizens.”

Disadvantaged communities, as they should, are to receive 40 percent of the funds.

While we urge our local school officials to bone up at the Oct. 11 webinar and to apply when the funding period opens Nov. 29, we realize that replacing New York’s more than 50,000 school buses with electric ones — which cost in the $300,000 to $400,000 range as opposed to the $100,000 to $200,000 for diesel buses — along with the charger and facility costs will dwarf the current state funding.

The statewide total will be at least $20 billion. So, going forward, local support will certainly be needed.

But let’s look at transportation on a more granular level: the vehicle you drive.

Even before the current United Auto Workers strike, many manufacturers of EVs, including Ford, GMC, Rivian, R1T, Lucid Air, and Tesla had backlogs that could last months or even years partly caused by supply-chain issues like a shortage of semiconductor chips that started in 2021.

Only about 3 million cars in the United States are electric vehicles, which is about 1 percent of all cars, according to estimates made by the Biden administration in February when it announced its plans to create a “convenient, reliable and Made-in-America electric vehicle (EV) charging network.”

In July, Governor Hochul, in another upbeat release, had announced that the state had reached a milestone of 150,000 passenger EVs on the road, and that $29 million would be available for electric vehicle Level 2 charging stations as part of Charge Ready NY 2.0 and consumer rebates through the Drive Clean Rebate Program.

“New York’s climate and clean transportation leadership is reducing air pollution and emissions through solution-based investments in charging infrastructure and rebates,” said Hochul in the release.

We support whatever state or federal money is used to build a reliable infrastructure to allow travel in EVs. But much more needs to be done.

A recent letter to the Enterprise editor made clear the perils of travel in an EV without a reliable system of charging stations.

Tracy Mance of Guilderland was trying to get home from California. A delayed flight to Boston made her miss a connection so she rented a car to drive home to Guilderland from Boston’s Logan Airport, typically under a three-hour drive.

Mance picked up the rental at 1:30 a.m. and discovered it was three-quarters charged and would go 208 miles; home was 189 miles away. When she expressed her concern, the person at the car-rental counter told her she could make it; there was no other alternative.

“I didn’t make it,” Mance wrote. “With the steep terrain on the interstate, the battery life quickly drained to less than I needed to complete my trip.”

She got off the interstate, found a charging station, and charged for an hour before continuing, only to have to search again. With the help of a digital assistant, she located two more stations, but both were “inoperable.”

“I had to call my father to drive an hour one way to get me and bring me home,” said Mance. “What should have been an easy two-hour, 45-minute trip took over seven stressful hours.”

She also wrote, “I feel it’s important to let others know about what happened. What if it were winter and there had been no heat to stay warm? What if I were traveling with small children or an elderly parent that needed medication? There are too many ‘what-if’s’ to even list.”

The solution, of course, is a better system for charging stations.

The federal Inflation Reduction Act provides tax credits for up to 30-percent of the cost to install home EV chargers with a cap of $1,000. Businesses, too, get a 30-percent tax credit with a cap of $100,000 per installation.

Again, while state and federal incentives are essential, more needs to be done.

Chargers come in three levels. Level 1 equipment, according to Car and Driver, plugs into a typical household 120-volt outlet and is often included with the purchase of an EV, but won’t get you very far: An hour of charging will take you two to four miles.

The state’s Thruway Authority reports there are 21 Level 2 charging stations at 11 hubs along the Thruway. Level 2 stations provide 12 to 32 miles of driving for each hour charged, similar to what Mance experienced at her first stop. The gauge had told her it would take about seven hours to fully charge.

Level 3 covers a range of 100 to 250 miles after 30 to 45 minutes of charging. Unlike the first two levels, Car and Driver explains, Level 3 setups connect to the vehicle by way of a socket with additional pins for handling a higher voltage, typically 400 or 800 volts.

The Thruway has 33 Level 3 charging stations at 15 charging hubs. More are needed throughout the state.

We’ve covered the installation of chargers locally and anyone can use the state’s online Electric Vehicle Station Locator to find one. If you type in Altamont’s ZIP code, for example, you’ll see a list of stations including at the Altamont Free Library, Orchard Creek, Phillips Hardware, and Guilderland Town Hall. They are all Level 2.

If consumers are to have confidence in buying EVs, Level 3 stations need to be as ubiquitous as gas stations are now.

To demonstrate “the promise and possibility of a healthier, environmentally friendly, low-carbon future” as the governor predicts and as most citizens want, we need to take the needed steps to realize that future.

The Biden administration’s goal that half of all new vehicle sales be electric by 2030, just seven short years away, will be unreachable if more Americans don’t trust their ability to power those cars.

A Gallup poll in April recorded 4 percent of Americans saying they owned an EV while 12 percent said they were “seriously considering” purchasing one but another 41 percent said they would not buy an EV.

Part of the problem is that most Americans don’t understand the effect driving a fossil-fueled car has on climate change. Sixty-one percent think use of electric vehicles helps address climate change “only a little” (35 percent) or “not at all” (26 percent), according to the poll.

Like so much else these days, the divide falls largely along political lines. Just 4 percent of Democrats answered “not at all” while 55 percent of Republicans did.

At the same time, 68 percent of Democrats thought use of EVs would help address climate change — “a great deal” (22 percent) or “a fair amount” (46 percent). For Republicans, just 3 percent thought use of EVs would help address climate change “a great deal” while 9 percent thought it would help “a fair amount.”

The actual numbers for New York, as we noted at the start of this editorial, show that transportation is second only to buildings for pollution, producing 29 percent of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions. That is an indisputable fact.

Six years ago on this page, we wrote about a grant-funded proposal that would have placed an EV charging station at the highway garage in Knox while at the same time checking the last box for the town to get a $100,000 grant from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority.

Amid a hostile crowd in the gallery, the Knox councilwoman proposing the project couldn’t even get a second on her motion to allow for town board discussion of the project.

We know change can be hard. But time is slipping away. Yes, we need government support for a reliable infrastructure of Level 3 charging stations. But we also need citizens to buy in to making the needed changes. Everyone’s future depends on it.