Good people need to be informed to act

What is a community newspaper?

Although we’ve thought about this almost every day for the last 40 years as we work to publish The Altamont Enterprise, we have felt more urgency to address that question since the Aug. 12 death of Joan Meyer at age 98.

She had, since the 1960s, worked at The Marion County Record — first alongside her late husband, Bill Meyer, and later helping her son, Eric Meyer — as an editor, local history columnist, and co-publisher. The rural weekly had a circulation of about 4,000 before Aug. 11 when police raided the news office and the home Mrs. Meyer shared with her son, which garnered widespread support for the paper.

Eric Meyer told Clay Risen who wrote Mrs. Meyer’s obituary for The New York Times that the coroner had concluded the stress of the searches was a contributing factor in her death the day after the raids.

His mother was in shock after the raid, had trouble sleeping, and wouldn’t eat the breakfast he brought to her bed at noon on Saturday, he said.

“She said over and over again, ‘Where are all the good people to put a stop to this?’ he said. “She felt like, how can you go through your entire life and then have something that you spent 50 years of your life doing just kind of trampled on like it’s meaningless?”

Mrs. Meyer died in midsentence, her son said.

We did not know Mrs. Meyer but we wept as we read that.

Eric Meyer is a member of the same organization we are, the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors. In 2002, Bill Meyer, Eric’s father, was awarded the society’s Eugene Cervi Award for excellence in journalism, particularly for public service through community journalism.

Born in 1906, Cervi was the son of a coal miner and “had a natural feeling for the little man, for the poor families of America. His father named him after Eugene Debs, socialist, union leader, and presidential candidate, who received nearly a million votes in the 1920 campaign,” wrote Houstoun Waring in Grassroots Editor, published by the society.

Waring also noted, “Gene Cervi was at home with the editors of ISWNE, people who regarded the great issues of the day as worthy of their attention and efforts.”

Waring, a Georgia newspaperman, was editor of the Littleton Independent and known for his philosophy that weeklies “should cover the world — not just the potholes on Main Street.”

The response to the raid from society members was swift. “When they attack one of us in this way they attack all of us. I’m hopeful the editor is getting assistance from neighboring newspapers in getting out an issue,” wrote one member, Kathy Tretter, editor and publisher of the Ferdinand News Spencer County Leader in southern Indiana, on the society’s listserv just after the raid.

The police had seized the computers, cell phones, and server needed to publish a newspaper — the modern equivalent of abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy’s press being thrown in the Mississippi River.

ISWNE, in its August newsletter and email updates, kept members informed. A local businesswoman had alleged the Record had illegally gotten information on her drunk-driving license suspension. Eric Meyer said the information from an anonymous source was verified through government records but the story was never published.

The Wednesday after the raid, Aug. 16, The Marion County Record came out on schedule with the banner headline “SEIZED ... but not silenced.

That same day, the search warrant granting the Marion police permission to carry out the raid — ostensibly to enforce a computer crime law — was withdrawn by the Marion County attorney, and the seized items were returned. A forensics team was hired by the paper’s attorney to investigate whether law enforcement accessed any of the paper’s records.

Also on Aug. 16, the ISWNE board issued a statement saying the society “is gravely concerned over the apparent government overstep and disregard for First Amendment protections afforded newspapers and journalists that took place last week during a raid of the Marion County Record in Marion County, Kansas, and the home of Eric Meyer, publisher and editor …

“As an international organization of newspaper publishers, owners, editors, journalists, and academicians, we wholeheartedly condemn the actions taken to silence and intimidate our colleagues who have been targeted in this incident.”

The Marion City Council met on Aug. 22 for the first time since the raid and its agenda stated, in capital letters followed by 47 exclamation marks, that it would not comment “on the ongoing criminal investigation.”

Big media outlets continue to cover the story as they have with other recent incidents where reporters or publishers of local weekly, community newspapers have been threatened.

It’s good they do because small newspapers like ours often lack the resources and reach to successfully combat local forces. In the 14 years between 2004 and 2019, a quarter of the newspapers in our nation have shut down — most of them are small community papers like The Altamont Enterprise and the Marion County Record.

Many large regional dailies have had to cut back on reporting in the midst of the digital shift away from print advertising. Without local reporting, democracy suffers.

But much of the coverage from big media on the Marion paper or on other community weeklies that have been threatened or sued out of existence focuses on local people who feel a weekly newspaper should be a booster of the community.

Kevin Draper begins his front-page New York Times story, “Raided Paper Hailed From Afar Gets Mixed Reviews at Home,” with a list of complaints about the Marion County Record from locals, like two recent deaths being handled insensitively or an opinion column being too harsh on the poor quality of children’s letters to Santa.

Draper writes that many locals see the police search as “a natural, if unfortunate, outgrowth of rising tensions between the community and The Record’s coverage. Some described the weekly paper as too negative and polemical.”

Draper, for instance quotes a Marion grocer, saying, “The role should of course be positive about everything that is going on in Marion, and not stir things up and look at the negative side of things.”

While the paper’s recent edition published numerous messages of support, “few seemed to be from locals,” Draper wrote.

We wholeheartedly agree with Eric Meyer’s response: The paper’s journalism makes the community stronger.

Draper breezily asserts, “News organizations, small and large, often rub residents the wrong way, particularly when they aim to hold power to account.”

We maintain it can be vastly different for a large media outlet like The New York Times to hold power to account than a small weekly, both in the resources to uncover the news and then in the ability to have reach with publication.

In 2008, we won our first Golden Quill award, which is given by the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors for courageous editorial writing.

Professor Ben Burns, the director of the journalism program at Wayne State University in Michigan, which housed the ISWNE conference that year, was the judge who selected our editorial as the best. Burns had been a juror for the Pulitzer Prizes and had over 30 years in the newspaper business.

“‘We, the people, are responsible for what our government does,’ exactly fulfills that charge,” said Burns of the Enterprise editorial by that name. “The newspaper pointed out the problems of an individual and called government officials to account for their handling of that problem. It is in the best tradition of journalistic opinion.”

Burns noted in his comments that weekly editors have a much greater risk than those at larger outlets to tell the news the way it is, because they are so much closer to their communities.

“The subjects of editorials are not held at arm’s length, but are the folks the editorialists may see every day,” said Burns. “It is considerably easier to toss thunder bolts from Mt. Olympus than it is to constructively criticize a person you might run into at the local grocery store the next day.”

Through the years we belonged to our state press association, which had been geared for weekly newspapers, we won the statewide award for community leadership more than any other paper. The awards were not for boosterism but rather for coverage that led New Scotland townspeople to reject a big-box mall, coverage that helped protect an important habitat at the foot of the Helderbergs, coverage that led to a citizens’ vote on multi-million-dollar project in Westerlo.

“They really have their fingers to the pulse of the community they serve,” said the association’s director in bestowing the award one year.

That brings us back to our opening question: What is a community newspaper — and who are we serving?

“Community” is a word that is frequently used these days to describe a body of people with similar characteristics or interests, as in “the LGBTQ+ community” or “the handicapped community.”

These labels certainly have their merit, helping to group together far-flung individuals, people who may not know each other.

But our use of the word is more inclusive. Our readers may be gay, they may have a handicap, they may be white, they may be Black, they may be atheist, they may be Jewish, they may be progressive, they may be conservative, they may be Democrats, they may be Republicans, and so on.

All we know for sure is they live in or have a connection to a particular place — Albany County, New York. In short, they form a community — they live together perhaps not in harmony but, if we can help it, at least with an understanding of one another.

We try to serve them by giving them news, as honestly and fairly as we can, that may be of use to them. Sure, we have things like calendar listings where you can find out about an upcoming class reunion or church supper; or Library Notes, where you can decide what book you’d like to discuss with others or where you can bring your child for story time; or Senior News with menus for meals and descriptions of upcoming trips.

Those are the kinds of things that the grocer in Marion, Kansas, would probably approve of. He’d probably like it, too, that we write obituaries for free because we believe every life in our community is important.

But we also write stories on topics he and others might label “negative.” If a house burns, we try to find out the cause of the fire. If students at a local high school feel there are racist or sexist or homophobic remarks being made about them, we look into it.

We write these stories because we believe the way to solve a problem is to first expose it and understand it.

We also write strong editorials and fill our opinion pages with a wide variety of fact-checked letters because we believe as Walter Lippmann said, “The theory of a free press is that the truth will emerge from free reporting and free discussion, not that it will be presented perfectly and instantly in any one account.”

While our newsroom has never been raided by police like the one in Marion County, Kansas, we have certainly been frozen out over the years by various officials who don’t like our coverage and, because we are small, feel they can ignore us.

The Albany County sheriff, for example, has rarely, if ever, returned a call from us or one our reporters since April 2016.

He called then because we ran an editorial he did not like about his circumventing the law.

We believe public officials, like sheriffs or mayors, should answer questions from the press for the good of the public rather than feeding information only to outlets they feel will benefit their cause or burnish their image.

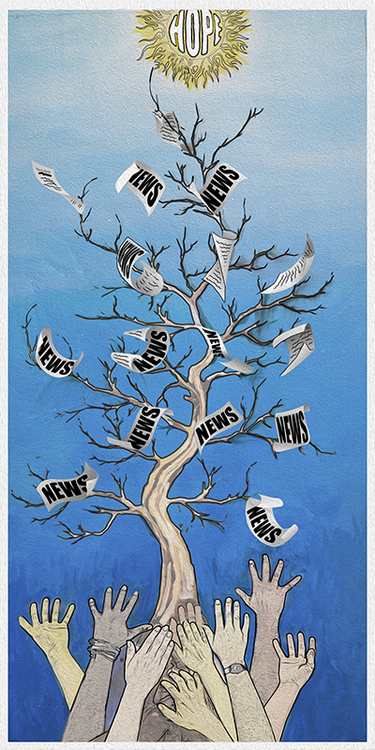

If we want the good people that Mrs. Meyer was asking about on her deathbed to be able to act, we need to keep them informed.

That is what a community newspaper does.