Inmate sues, alleging assault which sergeant denies

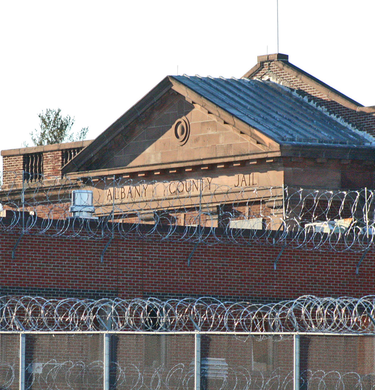

ALBANY COUNTY — An inmate at Albany County’s jail is suing a sergeant who works at the jail along with seven corrections officers, alleging his civil rights were violated and that he was “assaulted, battered, and brutally beat[en].”

While the inmate says he was beaten and his free-speech rights were denied, the responding sergeant says the assault claims aren’t true and free speech doesn’t apply in jail.

Danny Farrington was incarcerated at the jail, “based on a parole violation,” according to the complaint filed with the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York on April 15, 2022.

Farrington seeks a trial by jury and compensatory damages of $2 million as well as punitive damages and attorney’s fees, according to the court papers.

He is represented by Edward Sivin of Sivin, Miller & Roche, based in New York City.

In his response, filed on May 13, 2022, Sergeant Michael Poole, represented by Assistant Albany County Attorney Kevin M. Cannizzaro, “denies each and every allegation” contained in most paragraphs of Farrington’s suit.

The seven corrections officers — Heath Furbeck, Joseph Haley, Andrew Cohen, Padraic Lyman, Erik Gettings, Vincent Livreri, and David Dollard — filed similar responses.

Farrington’s suit claims his civil rights, including those guaranteed by the First, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, were violated.

Farrington’s suit says he “verbally complained and expressed his displeasure to Sgt. Poole about what plaintiff perceived as unjust orders and treatment by Poole,” which the suit describes as “a legitimate exercise of his First Amendment right of free speech and first Amendment right to petition the government for redress of grievances.”

In response, the suit says, “Poole forcibly brought plaintiff to the ground and then assaulted, battered, and brutally beat plaintiff without justification” and further “summoned other officers to participate in the brutal assault, battery, and beating of plaintiff.”

The assault, Farrington’s suit alleges, “included but was not limited to punching, kicking, and kneeing plaintiff, discharging chemical spray into plaintiff’s face at close range, and forcibly slamming plaintiff against the wall and ground.”

The suit describes the assault as “sadistic and malicious” and claims it “was not undertaken for any legitimate penological purpose, and further demonstrated a deliberate indifference to plaintiff’s health and safety.”

Each of the defendants “observed portions of the illegal and unconstitutional actions,” the suit claims, and “each deliberately failed to intervene.”

Because of the assault, the suit says, Farrington sustained “severe trauma to the head resulting in brain damage, endured and will continue to endure pain and suffering and loss of enjoyment of life, suffered and will continue to suffer economic loss, and has been otherwise damaged.”

Poole and Furbeck, the suit says, issued a written Inmate Disciplinary Report Form, making allegations “that Poole and Furbeck knew were false.” This included claims that Farrington had “chest bumped Sergeant Poole” and had “turned on Sergeant Poole.”

The suit claims that the report was issued “in retaliation” for Farrington exercising his First Amendment rights.

As a result of the report, the suit says, Farrington “was sentenced and confined to the Special Housing Unit” and “suffered an atypical and significant hardship in relation to the ordinary incidents of incarceration.”

In his answer, Poole responds that, whatever injuries or damages Farrington may have sustained “were caused in whole, or in part, or were contributed to by the culpable conduct and want of care on the part of the Plaintiff and without any negligence, fault, or want of care on the part of the Answering Defendant, or their agents, servants, and/or employees.”

Poole’s answer says further that his actions “did not violate the First Amendment of the Constitution in that the character of the speech used by Plaintiff was not entitled to protection under either the New York Constitution or United States Constitution.”

Poole’s answer also says, “Given that Plaintiff was located in a limited, non-public, and/or otherwise private forum his claims that his speech rights as protected by the New York Constitution or United States Constitution were violated are meritless.”

Poole’s response also says that “the force allegedly used against Plaintiff was objectively reasonable in view of the totality of the circumstances existing at the time they allegedly occurred.”

The last available court paperwork on file is a June 9, 2023 letter written by Cannizzaro, the defendants’ county attorney, to Judge Christian F. Hummel, asking for an extension of the June 26 discovery deadline.

“To complicate the scheduling, Defendants have had to balance the work/ summer vacation schedules of the eight (8) aforementioned witnesses, the staffing needs of the Albany County Correctional Facility, as well as the undersigned’ own litigation calendar,” wrote Cannizzarro.

Cannizzarro listed various scheduled deposition dates with the latest being for Poole, Livreri, and Dollard — all on July 10.

Jail policy

Four years ago, after four young men, transferred from jail on Rikers Island in New York City to Albany County’s jail while awaiting trial, sued both the city of New York as well as Albany County, alleging assault, The Enterprise filed a Freedom of Information Law request for Albany County’s policies on, among other topics, use of force in its jail.

At that time, Chief Deputy William Rice told The Enterprise that policies at the jail are ever-evolving. “Every year, we do a policy review,” he said.

Corrections officers, Rice said, get training at a corrections academy and sheriff’s deputies are trained at a law-enforcement academy.

Rice said of jail employees, “Every one goes through training. Every one is issued policies and procedures.” The documents are fully reviewed, and signed, he said. “It’s all done through the training unit.”

Albany County provided a 16-page document on physical force that says it is to be used “only to maintain the safety, security and good order of the facility.” The policy further states, “All force must be used in accordance with all laws, statues [sic], regulatory guidelines and department regulation as appropriate.”

The policy defines “hard restraints” like handcuffs, leg irons, and belly chains; “soft restraints” like leather belts, wrist and ankle restraints, and the restraint chair; and Conducted Energy Devices, known as CEDs, like tasers, electronic stun shields, and electronic restraint belts.

“Any CED may not be used to punish, discipline, or retaliate against an inmate,” the rules say, naming four “strictly prohibited acts,” such as, “Stunning an inmate after he/she has ceased to offer resistance.” Planned uses of CEDs are to be videotaped.

The policy has a table on the “Use of Force Continuum,” illustrating the “progression of force.” It notes that the goal is de-escalation and that the inmate always determines the level of resistance.

At the bottom of the continuum is an inmate’s verbal or visual resistance for which an officer can respond, for example, with verbal directions. Moving up the continuum, an inmate’s passive resistance may be met with aerosol, soft-hand techniques, escort maneuvers, or CED stun devices.

For active resistance, the response options are the same except soft-hand techniques are replaced with hard-hand techniques. For combative resistance, impact weapons, non-aerosol chemical agents, CED stun devices, and less-than-lethal munitions are to be used.

For destructive or lethal actions by inmates, deadly physical force, firearms, or CED stun devices may be used.

“Give the inmate a chance to comply and de-escalate,” says the policy. “As an officer you are not the aggressor, the inmate is. Only the inmate can escalate the situation, not the staff.”

The policy further states, “Physical force shall require authorization by a supervisor or other competent authority, prior to its being used. The exception is when there is an imminent danger of harm to staff, inmates or the public, or to prevent an escape and the staff member present believes immediate intervention is required to prevent the danger or harm.”