Guilderland EMS pitches policy to keep from being ‘held hostage’ at hospitals

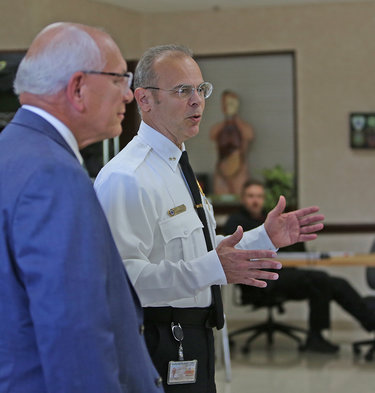

Enterprise file photo — Michael Koff

Jay Tyler, director of the Guilderland Emergency Medical Services, right, led Congressman Paul Tonko on a tour of the town facility last month. This month, Tyler proposed a new policy to manage the long waits EMS crews have endured at local hospitals as they take in patients.

GUILDERLAND — Town ambulance crews have endured long waits at local hospitals, worrying leaders that they won’t be able to respond to residents’ 911 calls.

The waits have grown longer over the last several years.

“Sometimes we’ll be delayed at the hospital an hour up to four hours,” said Jay Tyler, director of the Guilderland Emergency Medical Services, known as GEMS. “They’re really holding us hostage there. We have to treat the patient; we have to monitor the patient.”

Consequently, Tyler, who chairs the EMS Patient Offload and Delay Committee, which is looking at the problem regionally, has proposed a policy to standardize the times crews spend at hospitals based on how stretched thin they are.

Guilderland Town Board members, at their Nov. 1 meeting, were receptive to Tyler’s proposal but want to fine-tune it. They plan to work on the policy before their next meeting since Tyler’s goal is to have it in place by the start of the new year.

Tyler noted the problem is nationwide as many hospitals face staff shortages.

He presented the board with charts and graphs showing a steady increase in GEMS waiting time, from 10,561 minutes (roughly 176 hours) in the first half of 2019 to 23,925 minutes (nearly 399 hours) in the first half of this year. So the time more than doubled.

Similarly, in that same three-year period, the cost has more than doubled — going from $26,133 in unit hours to $59,244.

“So, if you can imagine two, three, four, five crews if you include Altamont Rescue Squad all at the hospital …,” Tyler told the board, “if someone’s dialing 911 — maybe there’s major trauma, or a heart attack or stroke — there may not be any crews to respond.”

Even crews from neighboring towns, which typically cover for each other when needed, he said, may be similarly tied up, waiting at hospitals.

Federal law makes the hospital responsible for a patient once an ambulance reaches hospital property, and EMS remaining with the patient is voluntary.

Tyler asserted of hospitals, “They’re relying on EMS to staff their hospitals … It’s a public-safety risk.”

Most of the time, Tyler said, patients are stable when GEMS crews deliver them to local hospitals, but sometimes they are in critical condition.

“We’ll travel with lights and sirens to the hospital only to be told to wait on the ramp and treat the patient …,” said Tyler. “Sometimes they’re treating the patient for hours and hours,” he said of his crews.

The policy Tyler is proposing, he said, “will give us a level playing field with the hospital.” He is frustrated though because, Tyler said, the calls he has made to local hospital leaders to discuss the policy have largely gone unanswered.

Three levels

The policy sets out three levels, each with a shorter waiting time based on availability of ambulance crews:

— Condition Green has a 45-minute maximum wait and applies when the majority of ambulances, two to five, and their crews and equipment are available for the next emergency call;

— Condition Yellow has a 30-minute maximum wait and applies when the number of available ambulances drops to one or two due to more calls or longer hospital delays.

“This is when the medical need begins to tax the system, yet things are not absolutely critical,” a draft of the policy says. “Response times have increased to 1 ½ to twice normal response time.”

In rural areas, the policy notes, Condition Yellow is reached “fairly rapidly because of limited resources available; and

— Condition Red says “all offloads will be immediate” and has a 10-minute maximum. Red is reached when no ambulances are available in town.

In each of the levels, the draft policy states, that, at set intervals, the EMS crew will apprise the charge nurse or triage nurse of the ticking time frame and will also let the GEMS Communication Center know of the delays. EMS crew members are advised to take their radios inside the hospital with them to stay aware of changes.

In each case, the draft policy states, “If a stretcher or location is not provided, the EMS crew will create an offload option, which may include triage chair, triage stretcher, vacant stretcher, wheel chair or foldable cot.”

When the patient is left at a hospital, the policy says, “the EMS unit may leave the patient in the department and return to service after giving either a verbal or written patient care report (can be quick form).

Board response

Councilwoman Amanda Beedle, who praised GEMS for leading with the policy, wanted to be sure that GEMS was either reimbursed for equipment — like wheelchairs, cots, or stretchers — left with a patient at a hospital or paid for the equipment by the hospital.

Supervisor Peter Barber and Councilwoman Christine Napierski, both lawyers, were concerned that there be written documentation that a hospital had taken on the care of a left patient; the legislators will meet with Tyler and others to make this part of the policy.

“I don’t think we should ever rely on a verbal notice,” said Barber, stating it is important to “get something in writing.”

The draft policy states, “The overall most important concept is that this is not a license to ‘drop off’ a patient at a hospital. With each patient, we must identify when the patient requires active monitoring by a medical professional. In that event, the EMS crew will treat and monitor the patient until they are able to turn them over to the appropriate hospital staff.”

Barber asked if backed-up hospitals were letting Guilderland dispatchers know to divert to another hospital.

“We would prefer the hospitals go through the Department of Health,” said Tyler. “That’s the way they should be going on diversion,” he said, noting that the department has a dashboard and “certain patients have to go to certain hospitals.”

The state’s health department has a survey form online for EMS agencies to report long wait times at hospitals.

Tyler said that sometimes his crews are waiting at a hospital “with seven, eight stretchers ahead of us with no triage.” Triage is used when resources are limited, rationing care to those who need it most and serving them first.

Barber asked if the EMS crews could legally leave to which Tyler responded, “If we left, we’d potentially put them in EMTALA violation. It does happen.”

He was referring to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act enacted by Congress in 1986 to ensure public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay.

As Napierski and Barber discussed potential legal ramifications, Tyler stressed to the town board, “The policy doesn’t have anything to do with leaving.”

He also said, “If I’m asked to satisfy a legal requirement or save someone’s life, I’m going to try to save someone’s life. We’ll deal with the legal stuff later.”

Napierski suggested a policy in writing so that an “EMT knows when it is safe to leave a patient.”

“It would be almost impossible to document every situation ….,” said Tyler. “We have to rely on them to use good clinical judgment,” he said of his staff.

Tyler concluded that the new policy, once reworked and adopted by the board, would give GEMS “a standard operational plan so everybody knows how to deal with it.”

Other EMS agencies may adopt it and the hospitals will know what to expect, he said.

“The policy will also give us a level playing field so the hospital knows that you can’t just hold us hostage,” Tyler said. “We’re not your staff. We have to get EMS crews back into the town and back into the cities to answer 911 calls.”

“It’s not a solution,” he said of the policy, “but it’s a way for us to keep the community safe and it’s a plan for us so that everybody knows what we’re doing.”

Barber concluded, “All eyes are on you, Jay … You’re kind of the leader of the insurrection.”

“It’s not an insurrection,” responded Tyler. “It’s not EMS against the hospitals. We understand the hospitals have the issues there … They should not become EMS issues. We have our own issues.”

Tyler said, in his opinion, hospitals “need legislative remedies” for their problems of understaffing.