In the fight against climate change, time is not on our side. Trees are.

In my youth, I strapped on my backpack and took a literary journey. I traveled to the western islands of Scotland, to retrace the 18th-Century footsteps of Samuel Johnson and his biographer, and friend, James Boswell. I felt prepared with my pen and blank book, my sleeping bag and tube tent, to lay my perceptions as a 20th-Century American woman against those of an Englishman and Scotsman, the great literary men of their era.

I was, of course, naive and foolhardy. One of my first nights in the stunningly stark landscape of the rain-soaked Hebrides, I discovered the practical value of trees. The tent I carried had no poles (no need for extra weight on a long trek) but was instead to be strung with light rope between two trees. There were none.

As I shivered in my now-wet sleeping bag, and read by flashlight the words of Johnson’s book, “A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland,” the passage about Auchinleck, Boswell’s ancestral home, took on new meaning. Johnson wrote of Boswell’s father, Lord Auchinleck, “It was, with the rest of the country, generally naked, till the present possessor finding, by the growth of some stately trees near his old castle, that the ground was favourable enough to timber, adorned it very diligently with annual plantations.”

Johnson saw Lord Auchinleck as a civilized man because he planted trees that would not benefit him in his own lifetime, but would be an asset to future generations.

I had, until that journey, taken the existence of trees for granted. With my mother, I raked the pine needles from the yard of my Pine Ridge Drive home every fall, piling them in sweet mounds at the corner of our yard. When I tented out on the hill behind our house, I was comforted by the whispering branches of trees. I liked watching the birds that nested there and the squirrels that raced straight up their trunks.

I had a favorite tree, a white pine, that stood majestically on a hill behind Guilderland Elementary School. I liked to climb the tree during recess and read there, undisturbed, with a bird’s-eye view of my classmates playing below.

Over the past three-and-a-half decades, I’ve used this page several times to extol the virtue of trees. Just three years ago, I urged our towns and villages to start tree-planting programs, listing the many advantages: cooling streets, conserving energy, saving water since shade trees slow evaporation from thirsty lawns, stopping water pollution as trees reduce runoff, preventing erosion, shielding us from cancer-causing rays, providing food — and healing us.

But now I write with new urgency.

Part of the Biden administration’s climate-change agenda is protecting 30 percent of our nation’s lands and ocean territories by 2030, known as “30 by 30.” Currently, about 26 percent of the United States’ ocean territories are protected but only about 12 percent of our nation’s land area is protected.

The protection is imperative because natural landscapes pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store carbon in trees, shrubs, grass, and soil.

On Saturday, the United States was among the nearly 200 nations at the Glasgow summit to agree at the close of the 26th Conference of the Parties — the first COP was in 1992 — to come back next year with stronger plans to curb carbon-dioxide emissions.

We’re running out of time; we can’t inch along as we have for 29 years in trying to solve this problem. Carbon emissions in this decade, the COP 26 agreement says, must be cut in half to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

We’ve all seen the havoc wreaked by climate change, from floods to fires. An entire nation, the Republic of Maldives, may disappear as sea levels rise because there is no higher ground for them to move to.

It will only get worse unless the world works together to curb emissions and, simultaneously, to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

We can act on this initiative close to home. The Enterprise whole-heartedly supports a bill proposed last week by county legislator Jeff Perlee, who represents Altamont, Guilderland Center, and part of the Hilltowns.

Perlee told our Hilltown reporter, Noah Zweifel, that the county owns about 750 acres of forests that would be protected by the law if it passes.

The law would create a preserve and prohibit the disturbance of county-owned forests that span more than a half-acre unless twice the value of the removed trees is put into a fund to be used to plant more trees or buy similarly forested lands.

Right now, the county is evaluating a development proposal for a solar farm on 11 acres of county land between the airport and Ann Lee Pond, which would require cutting several acres of black locust trees.

The legislative intent of the bill says that white pine and black locust trees, once abundant in Albany county, are “particularly effective at carbon sequestration.”

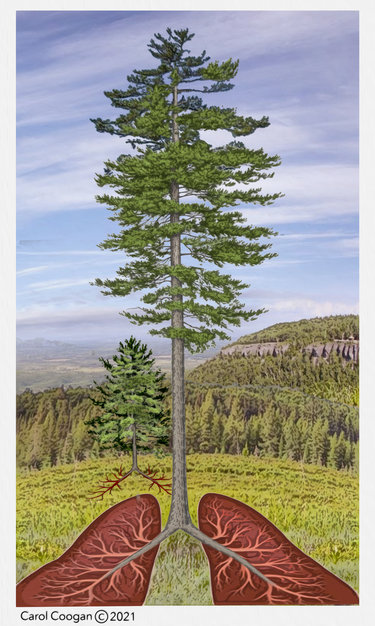

The section outlining the law’s intent is compelling in its straightforward simplicity: “Trees play an essential role in the survival of our planet,” it says. “Trees mitigate temperature fluctuation and lower air temperatures. Trees prevent soil erosion, regulate the hydrology of soil and groundwater levels and absorb surface water, preventing it from flowing into built-up and paved areas that contain pollutants that contaminate our waterways.

“Trees provide aesthetic comfort to urban landscapes and help delineate and buffer areas of current and future development. Through photosynthesis, trees sequester harmful carbon dioxide and release life-giving oxygen …. By regulating the exchange of energy and water between Earth’s surface and atmosphere, trees are our planet’s primary defense in the battle against global warming.”

Perlee says he supports the solar project proposed near Ann Lee Pond and wants to make sure it is not compromised at the outset by an environmental misstep.

And so he has proposed a law that would not nix the solar facility but, rather, would require a survey of the trees to be cut and provide a metric for determining their worth. The law would require that two times the value be placed in an account reserved specifically for purchasing replacement forest property.

The county executive would have no more than a year to identify and cause to be purchased a replacement forest or land suitable for planting a replacement forest.

While some towns have developed plans that preserve certain land uses — New Scotland comes to mind with its conservation of agricultural lands — we like this proposal because it allows for some flexibility.

If the county wants to develop a parcel for something deemed worthwhile — a solar facility in this example — it must recreate or purchase the forest that was lost.

While this law does not affect private lands, we would remind owners of forested lands, particularly in beautiful areas like the Helderberg Hilltowns, that such lands can serve as a means of spurring the economy since tourists are drawn to forested areas for their beauty.

We realize now that Johnson’s thought, which I read by flashlight in a soggy tent so long ago, was not a new one. Marcus Tullius Cicero, the Roman statesman and philosopher, wrote that the diligent farmer plants trees for which he himself will never see fruit.

Such tree-planting is an apt metaphor for modern life. In our post-industrialized society, we, as members of the human race, must sow seeds now if our civilization is to continue for future generations.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor