Hochul on aid to renters: ‘I want the money out — now’

ALBANY COUNTY — New York State is doing a poor job of getting federal aid to renters who have suffered during the pandemic, according to a report issued this month by the state’s comptroller, Thomas DiNapoli.

The state’s moratorium on evictions ends on Aug. 31.

In her first press conference, on Tuesday afternoon, Governor Kathy Hochul said she is “not at all satisfied with the pace that this COVID relief is getting out the door.” She named picking up the pace as one of her top priorities.

“I want the money out — and I want it out now,” she said. “No more excuses and delays.”

Hochul, who was sworn into office at midnight on Monday, said she had met with Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins earlier on Tuesday.

“We are unified in our sense of urgency that this money get it out to people in need,” said Hochul. “We are launching a new targeted campaign to reach more New Yorkers on rent relief. We are forming a real partnership with legislators, the City of New York, other cities and counties to get the job done.”

She also said that more staff is being hired to process applications and that she is assigning a “top team to identify and remove any barriers that remain.”

Hochul concluded, “New Yorkers should know, if you apply and qualify for this money, you will be protected from eviction for a solid year. Let me repeat. If you apply and qualify, you will not be evicted for a year.”

So far, more than 46,000 tenants have had their applications provisionally approved and rent relief funding set aside for them, but in some cases, small discrepancies in information between the tenant and landlord applications or the need to reconcile landlord accounts are delaying payments from being sent out, according to a Thursday evening release from the governor’s office.

The reassigned vendor staff “will work proactively to rectify these issues so direct payments already set aside can be disbursed,” the release said.

Up to $2.7 billion in emergency rental assistance is available for low- and moderate-income New Yorkers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The program helps with up to 12 months of past-due rent, three months of prospective rental assistance, and 12 months of utility arrears payments to eligible New Yorkers, regardless of immigration status.

Since the program began accepting applications on June 1, the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance has either distributed or obligated more than $680 million in federal funding, including more than $200 million in direct payments to landlords.

Applicants to the program automatically receive protections from eviction while their application is pending.

To receive assistance, a landlord must agree to waive any late fees due on past-due rent; and not increase the tenant's monthly rent or evict them for one year, except in limited circumstances.

“There are billions in federal aid to help renters who fell behind on payments in the pandemic, but this money isn’t getting to them,” said DiNapoli in a statement, when he released his report earlier this month. “The state can and must do a better job getting this aid into the hands of New Yorkers that could face evictions.

“New York’s Congressional delegation has pushed for more efficient distribution of funds, while lawmakers have rightly proposed extending the state’s eviction moratorium. We must make sure that we don’t lose these critical funds, and that the renters most in need of help don’t get left behind.”

New York was the only state that did not distribute any Emergency Rental Assistance Program funding through June 2021, the report says.

The first round of federal funds, approved in March 2020, included strict eligibility guidelines requiring proof of a pre-pandemic rent burden. Funding approved in December 2020 and March 2021 loosened the guidelines, expanding eligibility to low-income households that could prove loss of income.

Last year, DiNapoli’s report says, New York State provided $100 million in federal aid through the Division of Housing and Community Renewal under its COVID Rent Relief Program. It awarded about half of the funding in subsidies to households that applied, largely because of strict eligibility guidelines that required renters to prove they had been low-income and rent-burdened before March 1, 2020, leaving the other half of funds untouched for aiding renters with direct relief.

Low-income households are defined as those that earn less than 80 percent of the area median income. Rent-burdened households are defined as those that spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on rent.

With low-income, rent-burdened households as a measure, more than 1 million homes across New York State are likely to be eligible for the program.

While the report focuses largely on New York City, it also includes data for some upstate countries, including Albany.

Albany County, according to the report, has 142,884 households; more than a third — 52,331 households — are low-income. About the same number — 52,702 households — are rental.

Nearly a quarter of Albany County’s households — 33,695 — are low-income rental households and nearly a seventh of the county’s households — 20,135 — are low-income, rent-burdened households.

The comptroller’s analysis shows that, before the pandemic, the effects of low incomes and rent burdens fell disproportionately on non-whites, immigrants, and those who lack a college degree, many of whom worked in lower-wage industries. The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on these same groups.

“Outreach efforts, technical assistance, and steps to streamline applications should be targeted to reach those most in need,” the report concludes.

The state has already committed to simplifying the application process and increasing the number of reviewers. The comptroller recommends other improvements as well:

— Targeting assistance and program enhancements by geography, language, industry, age, household language, and other pertinent characteristics;

— Monitoring the program in real time to improve application completion, fund disbursement and program outreach, and enhance technical assistance efforts;

— Updating educational and outreach materials to reflect the recent simplification of forms as well as translated materials in additional languages;

— Creating a feedback loop to help community-based organizations, housing nonprofits and local governments improve the application system and better assist tenants who require follow-up documentation; and

— Advertising the newly created eviction protections gained both from applying to the Emergency Rental Assistance Program and from the passage of the Tenant Safe Harbor Act, so that tenants understand their legal rights.

“If the first round of rent relief provides any cautionary tale,” the report concludes, “it is that some renters in need of help get left behind when the process is complicated and when tenants are left without proper outreach and assistance.

“These challenges may worsen, as many more could apply in the fall when the statewide moratorium on residential and commercial evictions ends August 31, 2021. Enhanced unemployment benefits will also expire the week ending September 5, 2021.”

Ongoing trend

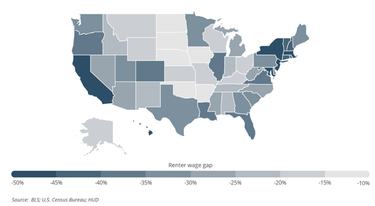

According to a recent report by the California-based Smartest Dollar, which looked at wages and rents across the nation, the renter-wage gap has been worsening in the United States in recent years, even before the pandemic.

Many of the people who have been most likely to lose jobs or wages during the pandemic are also more likely to rent than to own their homes, the study found. Meanwhile, COVID-19 has driven housing prices higher for both renters and home buyers due to high demand and low supply. As a result, the typical renter has less to spend on housing that is becoming more expensive.

Assuming full-time work and not being able to spend more than 30 percent of gross income on rent, renters cannot afford median rent for a one-bedroom rental in any large metropolitan area in the country, the study found.

The hourly wage needed to afford a one-bedroom rental in the Albany metro area is $18.92, the analysis said, but the estimated hourly wage for renters in Albany is just $13.77.

This represents a gap of -27.2 percent.

The analysis found that the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the Albany metro area is $984 per month and 35.8 percent of households are renter-occupied.

Albany renters are in a better situation, however, than many other metro areas. For the entire United States, the renter-wage gap is -37.7 percent. Across the nation, 35.9 percent of households are renter-occupied.

The pandemic has accelerated trends that have already been underway in the United States rental market for years, the study found. According to a recent report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, median gross rents increased faster than median rental household income between 2001 and 2018 in 45 states and in Washington, D.C.

Only the highest wage earners have kept ahead of the rising rent costs.

Since 1979, the wage growth of 90th percentile earners in the U.S. — the nation’s highest-paid workers — has consistently outpaced rents, while 50th percentile earnings more or less kept pace with rents before falling slightly behind after the last recession, the study found.

For 10th percentile earners, however, inflation-adjusted wage growth was not only lower than the growth rate for rents over the last 40 years, it was also negative from 1979 to 2017.

Current full-time workers would need to earn nearly $21 per hour to afford a median-priced one-bedroom apartment without spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent, the study found, based on a combination of data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Census Bureau.

Meanwhile, the estimated hourly wage for renters nationwide is just over $13 and the federal minimum wage has been locked in at $7.25 since 2009.

The rental wage gap is largest among coastal states. A map produced by Smartest Dollar shows New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland, California, and Hawaii with the largest gaps.