Race for 46th State Senate District

Three party candidates and one write-in challenger are all vying for the State Senate seat left open by incumbent Republican George Amedore, a developer who declined to seek a fourth term.

Taking Amedore’s place on the GOP ticket this year will be Conservative Richard Amedure, a resident of Rensselaerville and a long-time member of the town’s planning board.

Amedure’s main challenge comes from Democrat Michelle Hinchey of Saugerties, in Ulster County, whose campaign bankrolled a successful attempt to have Greene County resident Gary Greenberg tossed off the party’s primary ballot in June. Greenberg is now mounting a write-in campaign.

The fourth person seeking the state Senate seat is Green Party candidate and Voorheesville resident Robert Alft.

The 63-member state Senate has been under Democratic control since 2018. With three Senate districts not currently represented, each seat most recently having been held and subsequently vacated by a Republican, Democrats hold a current 40-to-20 advantage over the GOP.

As of February, according to the New York State Board of Elections, there were 190,347 active enrolled voters in the 46th District: 69,054 Democrats; 52,270 Republicans; 50,581 active enrolled voters without a party affiliation; 642 Green Party enrollees; and a smattering of enrollments in one of the state’s other third parties.

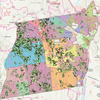

The 140-mile-long 46th District encompasses all of Greene and Montgomery counties, and parts of Albany, Schenectady, and Ulster counties. In Albany County, the district includes all or parts of Guilderland, New Scotland, Coeymans, and the Hilltowns of Berne, Knox, Rensselaerville, and Westerlo.

Hinchey has vastly out-raised her opponents this election cycle.

As of Oct. 20, her campaign, which began taking contributions as early as June 2019, had received 1,766 contributions (from 1,255 different contributors) totaling $446,000.

Approximately 93 percent, 1,651, of contributions to Hinchey, were for under $1,000, totaling $168,525; fifty-two donations were for exactly $1,000 for a total of $52,000; and 62 contributions were over $1,000 which amounted to $224,555.

Amedure had received 113 donations totaling $90,847 from 113 different contributors, as of Oct. 9, with 18 donations of $1,000 or more accounting for $70,150 of his total haul, of which about half ($34,100) came from just three contributors.

Greenberg’s $19,926 came from 52 different contributors — three contributions of $1,000 or more made up $14,500 of his total take, $12,500 of which came from just a single contributor: Greenberg himself.

Richard Amedure

Richard Amedure of Rensselaerville recently retired from the New York State Police after 31 years; the last four years, he was the head of the troopers’ union, he said.

Amedure said he thinks New York is headed down the wrong path: The bail and discovery reforms have “truly made us less safe,” there are fewer opportunities for young people, too many people are leaving, and taxes are too high. The taxes and regulations “are choking” small businesses, he said, causing them to leave the state.

On state finances amid the pandemic, Amedure does not support a millionaire’s tax.

When the state taxes people with the means to leave, Amedure said, “Guess what they do: Leave,” so it can become the law of diminishing returns, and less revenue could be raised with the millionaire’s tax.

“Taxes are too high in New York,” Amedure said, adding that the state went into the pandemic with a $6- to $7-billion budget deficit already. “We need to be fiscally responsible in good times so that, when we do have emergencies, we can weather the storm, so to speak,” he said.

The state came into the coronavirus crisis in bad shape by passing such things as $100 million for publicly-financed elections, he said, “We need to get rid of that.” The bail and discovery reforms had a fiscal note attached — $40 million for prosecutors, which was a one-shot deal thanks to an asset seizure through the Manhattan District Attorney; “next year, the money’s not there,” said Amedure.

There has been a backtracking on school financing, he said, referring to the governor reversing course on withholding 20 percent of aid to schools.

“The most onerous part of the last budget,” he said, was that the director of budget was given the discretionary power to alter the amount of money going to the local municipalities.

“He’s an unelected bureaucrat, yet he can make a decision on who — well, we don’t have enough money, we’re not giving it to you,” Amedure said, adding that the discretionary power was given to the director of budget in the last budget by the Democratic-controlled legislature. “They knew what was going to happen and they didn’t want to get the blame,” he said; the Democrats abdicated responsibility to an unelected bureaucrat in order to not have to take blame in an election year.

Asked how to close the state’s multi-billion-dollar budget gap — either raise revenue or cut costs — Amedure cited a recently released report by state Comptroller Thomas Dinapoli that said waste, fraud, and abuse were “a huge part of state government”; however, the waste, fraud, and abuse totaled only into the hundreds-of-millions of dollars.

“Bail and discovery reform laws are another example of a rush to legislation to create a political solution for a real problem,” Amedure said, adding that the interested parties, district attorneys and the police, were never brought in for their perspective. As executive director of the New York State Trooper Police Benevolent Association, Amedure said, he asked to be involved in the negotiations, and was told, “We know enough about it; we don’t need to hear from you.”

“They passed legislation that is absolutely unworkable,” he said.

Using the example of body cameras, Amedure said, the police unions were in the process of negotiating over the cameras, and there was an allotment of money that was going to be put aside for them and the cameras were going to be phased in. “And it was going to be a system that would have worked for everybody,” he said.

The body-camera legislation that was signed into law, he said, “cannot work” and creates a bigger discovery issue.

He used the example of a multiple troopers responding to a call when someone pulled over for speeding has a warrant out for their arrest for a much more severe crime, murder, for instance. At first, it’s two or three troopers with two or three body cameras, but soon there will be 10 troopers with 10 body cameras.

Footage from all 10 cameras will have to be downloaded, pieced together, and handed over to the defense, “physically unworkable,” he said, “and that’s why you see [assistant district attorneys] walking off the job left and right — because they are unworkable programs.”

It’s like the SAFE Act, Amedure said, stating that an ammunition registry was passed as part of the act some seven years ago, but the state doesn’t have the technology for such a thing. “And then the governor took away our IT department, so guess where that legislation sits?” he asked, answering himself, “It sits on a line waiting for IT spots to open up so we can create this registry, that 10 years after the SAFE Act still doesn’t exist.”

“I’m absolutely against single-payer,” Amedure said.

“I come back to the fiscal note, if they’re going to pass it, they’ve got to pay for it.” The estimated cost of single-payer health-insurance coverage for all New Yorkers is between $15o billion and $200 billion, in effect doubling the size of the state budget, currently about $180 billion.

Amedure said New York already has an effective health-care system; fewer than 5 percent of the population is not covered by some kind of health insurance.

Asked how to help the 5 percent of New Yorkers who still don’t have health insurance, he said, “They definitely need help,” and many did get the help when the federal government expanded health care under the Affordable Care Act, sometimes called Obamacare. In addition, there are New York State health-care exchanges, he said.

And, at the same time, while “we’re in the process of removing the waste, fraud, and abuse” from the system, some of that saved money can be reallocated toward helping insure the 5 percent of the state’s population who are still uninsured, with basic coverage, Amedure said.

He also said sometimes younger, healthier people choose to not have insurance, something that was not available under the Affordable Care Act — in December 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which eliminated the individual mandate, effective January 2019. If someone is under 30 and lives a relatively healthy lifestyle and chooses not to have health insurance, “that’s fine,” Amedure said, but that person should also have a low-cost option that covers critical care.

But for the 5 percent of New Yorkers who are uninsured, he said, “We would have to approach those individuals and see what the most cost-effective way to treat those folks are.”

As for a state-set single assessment standard, Amedure said that he’s “not a big fan” of the state coming in and telling its municipalities what to do, because it will invariably end up costing the city, town, or village. But if the state wants to come up with a single standard and is actually willing to absorb that cost, “then that’s fine,” he said.

Amedure points out that there is already an appeals process built into the system. “If you feel your taxes are too high, every year in the spring, there is a period, you can go down there, appeal it to the local jurisdiction,” he said. “If that person does not agree with your assessment, you can go on to the next level.”

So there is an appeals process, which is the main step of fairness, Amedure said; if a municipality is going to set a tax rate and not allow property owners to challenge it, that’s “very unfair.”

But if someone feels his or her assessment is incorrect, they “have to put their money where their mouth is,” and put together a case, comparable assessments of neighboring properties, for example, for why the assessment is too high, he said. And if the case can’t be made, “Guess what?” Amedure said. “You’re probably paying a reasonable, fair amount of taxes.”

The most responsive form of government is town government — “It’s right there,” Amedure said. As someone who was on the Rensselaerville Planning Board, he heard about if someone had an issue — not through email or by phone — directly. “They came to the town hall and we spoke,” he said. If there is to be a change in the way properties are assessed, he said, it will change from the ground-up.

On gun safety, Amedure said that he was a firearms instructor with the State Police for over 20 years, so gun safety is one of his core values, and he also said that training is an important aspect of firearms ownership.

“I believe in the private ownership of firearms; I believe in the Second Amendment,” he said. “I believe that, when the government starts impinging what types of guns and what kind of flash-suppressor you can have, it seems a little petty.”

There is a lot of knowledge out there, Amedure said, and firearms are not a complicated technology, so every time a new ban is put in place, a new work-around is figured out.

With long guns, he said, people should be able to purchase them, with a proper background check. “Shotguns are a staple in every rural home pretty much on the Hill,” he said referring to the Hilltowns. “And pretty much everywhere else.”

Amedure said that “most people are killed with illegal firearms.”

Asked how to limit the flow of illegal firearms, Amedure said, “Securing firearms is obviously a good [start], everybody should have their firearm secured. So if your house does get broken into, things don’t get fired.”

Asked about other priority issues, Amedure said, “I have two children, [who are] 26 and 24, and we’re trying to get this so we don’t have to have a next generation of New Yorkers leave. I want to help New York State be more business conducive, more friendly, so we can have more job opportunities here.”

Amedure said that the Mohawk and Hudson valleys have helped build America. “The Empire State was created right in these valleys,” he said. “And what we’ve done in the last 40 to 50 years seems to have done everything to reverse that trend.”

New York needs to embrace “legal” businesses, Amedure said, “when [General Electric] dumped those pollutants in the river that was permitted by New York State.”

Amedure continued, “And then New York State saying, ‘You’re responsible for it.’ I get it. GE should clean up their own mess, that’s 100 percent what should happen. But, if we’re going to keep the businesses here, we have to give them reasonable regulations and reasonable taxes, and then they can stick around and give our next generation jobs and reasons to stay here.”

Gary Greenberg

Investor and businessman Gary Greenberg is running a write-in campaign for State Senate because he wants to serve the people of the 46th District, he said, with his extensive background of public service.

His petition to run in the June 23 Democratic primary was thrown out in a court challenge because of faulty signatures.

Greenberg, who currently lives in New Baltimore in Greene County, was an Albany County legislator when he lived in the county; for the last four years, he fought for and won the passage of the Child Victims Act and Erin’s Law, he said.

On state financing amid the pandemic, Greenberg, who is a minority owner of Vernon Downs, a horse-racing track and racino, located in the town of Vernon in Oneida County, is a big supporter of putting sports gaming online. He said that the move would raise hundreds-of-millions of dollars for the state.

New Jersey and Pennsylvania currently have online gaming, Greenberg said, and New Yorkers are “crossing the border with their phones,” and, because they can bet on sporting events online, New York State is missing out on hundreds-of-millions in tax revenue

Greenberg said there are also three outstanding downstate casino licenses that have yet to be awarded, each of which he believes would bring in “a billion dollars each to the state.”

He is not against a millionaire’s tax, pointing out that there had been a millionaire’s tax that lapsed. But Greenberg also said you have to be careful because 1,000 people a day are leaving New York — 700 of whom are ending up in Florida.

On criminal-justice reform, Greenberg said, “Let me say this: I’m a supporter of the police” — there are a lot of good police officers in the district, and across the state and country. But he said it’s a good idea that there is some reform, citing as an example the need for more mental-health training.

Greenberg said he’s not for “defunding the police,” a phrase that he said can be misconstrued. He thinks what people want to do is to help the police, who are overworked and overstressed, especially amid the pandemic. Greenberg said he is “open to reform,” but he’s also “open to the fact that I respect police and I honor them.”

On single-payer insurance, Greenberg said that he is a supporter of the New York Health Act, and the reason he supports it is because “no person in the state should go without health care, good health care.”

Greenberg said his sister, who got lung cancer and died at an early age, went bankrupt paying medical bills. “No one should have to go bankrupt because they are sick, and no one should be denied health care because they can’t afford it,” Greenberg said.

The New York Health Act would help state residents and would provide individuals with good health care, he said.

Greenberg said voters have to study the candidates and find out what their solutions are to the problems, citing as an example when President Donald Trump first ran in 2016 and a lot of people who supported him had their “health care cut off.”

Greenberg would support a union carve-out similar to what was done in Affordable Care Act, and to what Michelle Hinchey supports.

Greenberg said there should be a single state-wide property assessment standard. It would make it a fairer system.

On gun safety, Greenberg said the SAFE Act had bipartisan support. The act, which became law in 2013, was passed in the Senate in a 43-to-18 vote; nine Republicans voted in favor of the act.

“A lot of people don’t like it,” Greenberg said of the SAFE Act, and he would be willing to review the law, adding that he would talk to the sportsmen in the 46th District to see how changes can be made that “everybody can be happy with.”

Greenberg is a supporter of the Second Amendment, saying “People have the right to bear arms.” But there are simply too many guns in society, he said, referring to the record-high shootings in Albany this summer and the 11-year-old boy in Troy who was murdered in a drive-by shooting, and broadly speaking as to what’s happening in cities like Chicago.

There are too many illegal guns on the street, Greenberg said, and he wants to go after the people who are selling the illegal guns to “basically teenagers.”

“If you’re 15, 16, you have a gun,” he said. “A lot of kids today in the inner cities, it’s the cool thing — I think we can do a better job of preventing violence in our cities and towns, and there’s too many guns on the street and we have to get those guns off the street.”

People who want to go hunting and fishing, he said, he’s all for it. But, when there are illegal guns in the wrong hands, something has to be done about it.

Asked how to get the illegal guns off the street, Greenberg said, “We have to get on the streets, in the cities particularly [and] enforce the laws, first of all, that we have.”

Why aren’t the police cracking down and taking the guns away from “these kids,” 15- and 16-year-olds, and 17-year-olds and gangs, Greenberg asked. “It’s a tragedy every time someone is innocently killed,” he said, and there needs to be a better way “to infiltrate these gangs and not make it so cool to carry a weapon.”

Asked about other issues, Greenberg said that there are a lot of farmers in the district who are hurting, and suicides have increased — they’ve also been hit hard during the pandemic.

He also said he supports Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy’s environmental bond act, and said that the state’s infrastructure needs a lot of work.

Greenberg said he doesn’t have the backing of any political organizations, then said, “But what have political organizations done for you?” Both mainstream parties, he said, “have gotten us in a terrible mess, haven’t they?” — not only in New York State but in Washington as well, he said.

Michelle Hinchey

Michelle Hinchey said she learned how government is supposed to work from her father, Maurice, a 20-year United States Congressman.

His death, in 2017, from frontotemporal dementia, was a “crash course” in how broken the health-care system is, she said, because, one would think, as a former congressman, he’d have great health insurance, but she said that her family had to sell some of its land to pay for his home care.

Hinchey, who grew up in Saugerties in Ulster County, graduated from Cornell in 2009 and worked in communications for 10 years.

She first got active in local politics, she said, with the 2018 campaign of now-Congressman Antonio Delgado. Hinchey said it’s important that the majority conference have upstate voices, citing as an example the need for an advocate of broadband in the state Senate, which is really not an issue for Democrats elected from the state’s cities and surrounding suburbs.

On finances in the time of coronavirus, Hinchey said, “This is really the most pivotal question of our time right now.”

The state can’t be run on an austerity budget, she said, adding that the federal government needs to step up with funding. But until that happens, Hinchey said, the state needs to be “more creative” with its revenue measures — she makes it clear that she doesn’t support increasing taxes on middle- and working-class families — but does support taxes on multi-millionaires.

Asked what multi- the millionaire tax should apply to, she said, people over $10 million to start.

The left-leaning Fiscal Policy Institute estimates that, if taxes were raised on a sliding scale on people earning over $1 million, a millionaire’s tax could yield the state an additional $4.5 billion of revenue — if only incomes over $10 million were taxed, New York State would take in an additional $2.27 billion in taxes.

But Hinchey also supports other revenue generators, like legalizing marijuana, which she said could yield another $300 million in tax revenue annually for the state. While she admits it’s not a lot in the grand scheme of the $13.3 billion budget gap: “It is $300 million we need,” she said, then there are the economic development impacts with legalizations, like those associated with agriculture in upstate New York.

On the criminal-justice reforms, Hinchey said that she spent a lot of time talking to community members as well as to members of law enforcement about the issue, and that everybody agreed that the system was broken and needed changing.

“I don’t think, no matter who you are, can look at those videos that we’ve seen over the last few months and not think something was wrong,” she said.

What’s “exciting” for the police departments of smaller communities of the 46th Senate District is that some of them are taking innovative steps, she said. In Lloyd, a town in Ulster County, for example, a lot of community outreach is being done, she said.

Hinchey said that more funding needs to be provided to address “root causes of many issues,” like more money for housing, mental-health services, on-call social workers, and expansion of addiction services.

At the same time, there is a need to be working with law enforcement to get back to community policing — a lot of police departments are part-time and therefore officers don’t know the people they are hired to “serve and protect,” she said.

Hinchey talked about the possibility of bringing social workers into the force, and said she has spoken with the State University of New York about a degree that emphasizes both criminal justice and social work.

On single-payer health insurance, Hinchey believes “fundamentally” that everyone deserves quality and affordable health care, and referred back to her father’s story about long-term care.

The New York Health Act is “exciting” to her, she said, but needs to better address long-term care, because, although it was finally included as part of the bill, it currently says “to be determined.”

Hinchey also made it a point to say that she would make sure union health-care plans are protected.

Asked how single-payer would compete against the other 49 states and the open market, Hinchey said, “It’s something we’re still looking into”; it’s something that would be funded by the state; and it’s an opportunity to provide people with better health care.

She also said that the plan would have to look out for people who work in the insurance industry, like the 400 who are employed in Kingston, the county seat of Ulster County.

On whether or not New York should follow the lead of most states and have a single assessment standard, Hinchey said, “Yes, I think so.”

“Right now, owning property, we’re penalized,” she said; many people who make less are paying more in property taxes than people who live in cities.

The cost of living in New York State is high, Hinchey said, and residents are being priced out of their home communities and a way needs to be found to make it more affordable to stay. For example, once a resident turns 65 years old, their property taxes no longer increase, Hinchey proposed.

“There is an inequality system here, in our property-tax structure — especially as it pertains to education,” she said. Adding that these are things that need to be looked at and overhauled “as best we can.”

On gun safety, Hinchey said that she grew up with rifles in her home and believes in responsible gun ownership and gun ownership in general, and that ownership is “part of our upstate culture.”

The only way amendments would be made to the SAFE Act would be if there were upstate voices in the majority conference, she said. “We know when it was passed, it was passed by people who didn’t really understand gun culture,” Hinchey said, citing as an example the number of bullets included in a magazine as something that should not have been included in the law.

Hinchey said that assault rifles, perhaps, could just be kept at a shooting range, under lock and key. “I don’t know if we need them necessarily in our homes, but it’s something we can definitely look at for how do we keep it safely at a gun range,” she said.

Asked about there being just too many guns, Hinchey said, “At a state level, I don’t believe anybody is taking guns away from people,” she said; if anything, that’s something that would happen at the federal level. Many people in the 46th, she said, are hunters, it’s how they “have food through the winter.”

But she said that red-flag laws — state laws that allow police, with the consent of a court, to temporarily take away firearms from people who are deemed to be a danger to themselves or to others — are important.

Asked about other priority issues, Hinchey pointed to infrastructure and the environment — “both things that I think are critical for our communities,” she said.

Hinchey said there is a desperate need for investment in broadband infrastructure; communities rightfully feel left behind because they don’t have access to something that, in 2020, should be considered a utility.

Many people knew lack of broadband access was a major issue before the coronavirus, she said; the problem has become more pronounced in the ensuing seven months of the pandemic. Some single-car families were faced with the choice of driving their children to a library parking lot where they’d have access to the internet or going to work, Hinchey said,

And the environment “not only provides to our quality of life,” she said, it’s also critical to the economy. Hinchey said bad corporate actors, of all sizes, are constantly trying to ruin that — for instance, by dumping of toxins, which happens across the communities of the 46th District, polluting the water, the air, and woodland quality. All of this will have to be paid for with more state money because the federal government has largely abdicated its role in this realm, Hinchey said, which is why more upstate voices are needed.

Robert Alft

Green Party candidate Robert Alft was living in Texas in the 1980s and working for Miller Brewing Company as a production supervisor when he and his wife, Margaret Lafond, came to realize that they needed a better place to raise their children, he said.

The family moved to Voorheesville in 1993, when his wife was able to get a job with the New York State Police, at which point Alft became a stay-at-home dad. As the couple’s children got older, Alft got a job driving a bus for the Voorheesville Central School District, where he worked from 2000 to 2017.

Alft said he decided to run on the Green Party line for a number of reasons, the first of which was the party had to defend its ballot line. In the past, both Democratic and Republican party candidates had “stolen” the 46th District’s Green Party ballot line, he said. And as the pandemic wore on, he said, it became clear that the typical two-party race would be devoid of important issues that he felt needed to be addressed.

Alft said that the people leaving the state are elderly residents, and that’s because property taxes are too high.

As far as taxing the wealthy, Alft referred to the quote attributed to the bank robber Willie Sutton, although Sutton denies ever having said it, who supposedly replied to a reporter’s question as to why he robbed banks by saying, “Because that’s where the money is.”

Alft said the money is on Wall Street and every year the state, through its taxpayers, hands back $16 billion collected on the stock-transfer tax, and what the governor doesn’t want to talk about is that this has been happening every year for 39 years.

“That puts a pretty big hole in our budget,” he said. “When I buy a car, I’m paying 8.5 percent on that transaction,” while stock traders, who pay the stock-transfer tax based on a sliding scale value of the stock itself and can pay as little as one-quarter of 1 percent on stocks that sell for over $20 per share, are getting a bargain that they already don’t want to pay.

Alft doesn’t think a higher tax on the wealthy will scare those residents from the state, an observation that is backed by a fair amount of evidence.

On the bail and discovery reforms passed by the state, Alft said, “This whole situation is very complicated.”

He said the key word in the bail-and-discovery question was “rushed”; however, the reforms were necessary because they addressed a long-ignored problem: The disparity between what happens to a poor person and what happens to a rich person when they are arrested. There are some people who “languish behind bars,” sometimes for as long as a year because that is when their next hearing is scheduled for, because they can’t meet the bail payments even on simple charges, Alft said.

In terms of the burden placed on district attorneys and the material those offices have to come up with, Alft said that may have not been well-thought-out, but, again, the new law was addressing a long-term problem where defense attorneys were not being given all the material they needed to mount a proper defense.

Now that bail and discovery reforms are law, and there has been time to see the issues associated with them, he said, they can be addressed. But, again, Alft said, it’s important not to lose sight of the issue: The intent of the law in the first place was to extend justice to all New Yorkers, not just the privileged few.

On health care, Alft said that the New York Health Act has been in committee since 2015.

Single-payer health would be “a great thing for New York,” he said, especially since it doesn’t look like the option will ever be offered at the federal level, regardless of who wins the presidential election.

The New York Health Act would give a lot of relief to county governments, Alft said, citing Medicaid as an example.

Medicaid is the federal program, administered differently by states, that pays for health care for people with limited incomes or with disabilities.

And county governments have no cost-control power over Medicaid.

Half of Medicaid funding comes from the federal government, while the states — rather, non-federal sources — are responsible for picking up the tab on the other 50 percent. The Medicaid law allows states to choose how they will pay for their half of residents’ medical expenses — the state can take on that entire cost or it can pass some of that cost along to its municipalities.

Eighteen states, including New York, have laws that mandate counties pick up a portion of non-federal Medicaid costs. No other state in the country has higher mandated county contributions than New York, which the Empire Center in 2018 put at $8 billion per year.

The current health-care system is also a burden for employers, Alft said, which have to pay high premiums for their workers if they, employers, want to give their employees good health insurance.

Alft said that a single-payer health-care system would ultimately end up being less expensive than the current for-profit system.

On the fair-tax question, Alft said, “I don’t know why we haven’t had that all along.”

If you look at what’s happening now, he said, “we’re trying to paper over” the disparities between affluent and poorer school districts by using state funds, an issue that has been exposed recently with the governor’s request to withhold 20 percent of state funding to school districts — some of which has since been restored.

School districts like Voorheeesville “didn’t feel the pinch,” he said, while city school districts, like in Albany and Schenectady, saw layoffs. “Anything the state can do to minimize that sort of discrepancy, from the rich and the poor areas of the state, I think is a good thing,” Alft said.

On the issue of gun safety, Alft, who is not a gun owner himself, said, “I don’t have any problems with the current gun laws myself, but I’m willing to listen.”

He said that he knows many people who own guns for hunting and sport, like target shooting, and people who own guns for self-defense, all of whom have a “legitimate right” to have those weapons. But, he said, it’s like anything else: A person has to have a license to drive a car and it has to be registered. “And I don’t think a weapon should be any different from that,” Alft said.

Speaking to the hysteria that “Democrats are going to take everyone’s guns,” Alft said that he’s never seen anyone who’s “legitimately” had a gun who had that problem. But, if that really is the case, he’s going to “sit up and listen real close.”

Alft also said the language of the Second Amendment, “a well regulated militia,” does leave open the door to some kind of regulation or licensing.

Asked about other issues he felt were important, Alft said, there were a number of issues that aren’t currently being discussed, and “the most important thing that seems to be left out of the political conversation lately is the climate crisis.”

California is on fire, the third hurricane this year is set to batter New Orleans, and the Midwest was “totally swamped” this year as well, he said.

Although New York State has yet to be impacted by the climate crisis, Alft said, there are places in the world that are experiencing climate change-related mass starvation, citing as an example the millions of children in Yemen on the verge of starvation. “We’re not doing anything in New York to stop the climate crisis — of any great impact,” Alft said.

New York State also needs to seriously consider ranked-choice voting, Alft said, which allows voters to cast their ballot for a preferred candidate and then, when that candidate is not one of the top two vote-getters, the voters’ ballot goes to their second-most favored candidate.

Maine has ranked-choice voting; in Massachusetts, it’s on the ballot.

Ranked-choice voting would allow for “an open discussion” and “open debate” of all parties involved in a race, Alft said; all too often, third-party candidates are often left out of the democratic process.

He said that he was recently left out of a candidates forum in Ulster County. “I was shut out entirely,” Alft said; it was just the two major-party candidates who were invited, although he added that he was included in the Oct. 13 League of Women Voters forum.