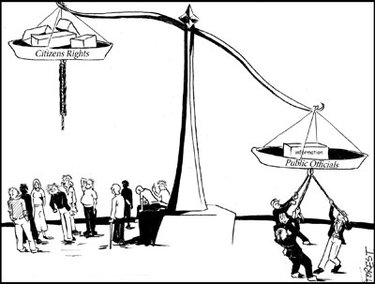

Public servants must be accountable

Illustration by Forest Byrd

Charles Reader, Ward Humphrey, James Murley: Three unrelated men.

Reader was a tenured music teacher at Voorheesville. Humphrey was the long-time superintendent of buildings and grounds for the Guilderland School District. Murley is the chief of police for Guilderland.

What they have in common is they were public servants with salaries that came from local taxpayers. And, all of them, in recent months, were placed on paid administrative leave. Reader and Humphrey have resigned; Murleys fate is still undecided.

We have received a steady stream of calls and visits and letters about these men. Many have raised questions about why they were placed on leave; quite a few have speculated on answers. Lately, some of the messages have been irate as an increasingly frustrated public wants to know why we wont tell the whole story.

Quite simply: We print as much truth as we are able to find.

We have, over the last few months, submitted dozens of requests under the states Freedom of Information Law and quite a few appeals as well. We understand that employers, whether school districts or a town, seek to protect their workers and themselves.

Our job is to find out what is rightfully a matter of public record.

From the Voorheesville School District, we obtained a copy of the superintendent’s Dec. 21 letter to Reader, placing him on leave and citing a pending investigation "into a new allegation that you have engaged in inappropriate conduct with a student of the District."

We also obtained a copy of a Jan. 19 agreement stating Reader had resigned "for various medical reasons" allowing him to be on paid sick leave until June 30. His salary this year is nearly $55,000.

So which is it is he sick or has he "engaged in inappropriate conduct"" If he’s sick, why wouldn’t he return to the district when well" If he’s not sick, and agreed to leave because of "inappropriate conduct," why should he collect sick leave"

The settlement further specified that the district will write a "neutral" letter for Reader if he seeks employment elsewhere. This makes no sense to us. If, on the one hand, Reader did nothing wrong, he should be able to teach at Voorheesville. If, on the other hand, he did something wrong, why would it be all right for him to teach at another school"

The case of Ward Humphrey is even more mysterious. While Voorheesville answered our FOIL request with the letter that gave a reason for the administrative leave, the Guilderland School District was not so forthcoming.

We were able to learn Humphrey was placed on administrative leave from his $73,000-a-year job on Dec. 4 but we don’t know why. We were able to obtain a copy of his agreement with the district which said the superintendent of schools had advised Humphrey he "is considering preferring disciplinary charges" against him.

Since Humphrey "denies any charges and any such charges could be vigorously defended," Humphrey and the school district decided to resolve the matter "without the need for a hearing or any other litigation."

Humphrey is looking for a new job, but we dont know why.

Chief Murley of the Guilderland Police Department, who earns $96,849 annually, is still on administrative leave. While Readers and Humphreys administrative leaves and later resignations were covered solely by The Enterprise, Murleys leave has attracted widespread media attention, which the towns supervisor, Kenneth Runion, attributes to the town sending out a press release.

We have noted that Murley is frequently not at his post. His absenteeism started in the fall of 2004 when he missed 40 days of work due to Lyme disease, which he got from a deer tick bite; he was hospitalized a few times.

Several of our FOIL requests to the town of Guilderland have been denied. We are currently appealing the denial of attendance records for Murley. Runion has written us that the "personal privacy protection" part of the state’s Public Officers Law means those records can’t be released.

A 2001 opinion from Robert J. Freeman, executive director of the state’s Committee on Open Government, says otherwise. Freeman refers to the part of the Freedom of Information Law to which Runion also referred that authorizes an agency to withhold records to the extent that disclosure would constitute "an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy." He goes on, "With regard to records pertaining to public employees, the courts have found that, as a general rule, records that are relevant to the performance of a public employee’s official duties are available, for disclosure in such instance would result in a permissible rather than an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy."

He cites seven cases. One of those cases resulted in the state’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, unanimously affirming a decision granting access to records indicating days and dates of sick leave claimed by a named municipal police officer. The court found that "the public has both economic and safety reasons for knowing when public employees perform their duties and whether they carry out those duties when scheduled to do so."

The Freedom of Information Law, the court said, allows the public a way to obtain information "concerning the day-to-day functioning of state and local government thus providing the electorate with sufficient information ‘to make intelligent, informed choices with respect to both the direction and scope of governmental activities’ and with an effective tool for exposing waste, negligence and abuse on the part of government officers."

"According to those decisions," writes Freeman, "it is clear that public employees enjoy a lesser degree of privacy than others, for it has been found in various contexts that public employees are required to be more accountable than others."

We intend to hold our public servants accountable and that includes those who keep the records.

Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor