Brevity, levity, and polemics

The Enterprise — Marcello Iaia

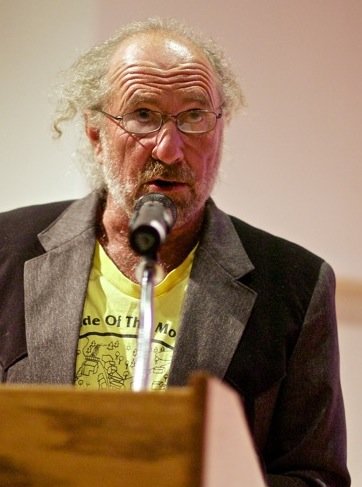

The craft: Andrew Blackwell’s palms are opened, flanking the microphone that captured and carried the stories, poems, and jokes of guests at the Carey Center for Global Good on Saturday. Blackwell told of his adolescent confusion with the words “subtle,” which he had only read, and “suttle,” which he had only heard.

RENSSELAERVILLE — The people wanted to sit inside, and, with a show of hands, so they did.

In its fourth year, the Festival of Writers in Rensselaerville had scheduled its Saturday night of storytelling to be held outside as a kind of after-hours campfire featuring writers and actors of national renown reading the work of local writers.

“It’s going to be cold,” a woman called out from the packed and dim theater. Mosquitoes were cited. A vote was called.

The four-day festival benefits the Rensselaerville Library by bringing writers from the region, many of whom work or live primarily in New York City, to the small, historic hamlet in a town of 1,843.

Readings and workshops focused on the twin crafts of writing and reading that slid naturally off the social and informal atmosphere of friends entertaining friends on Saturday night in the Carey Center for Global Good in Rensselaerville.

“Your town is magical,” said Lizz Winstead, a boisterous comedian and co-creator of The Daily Show, who introduced keynote speaker Joan Walsh, editor-at-large of Salon.com, and hosted the indoor version of “Night Owls” on Aug. 17.

Voices

“It’s smaller, but it’s more intimate,” said writer Helen Benedict, comparing this year’s festival to others she has attended. Benedict has written a total of 11 books, both fiction and non-fiction, and lives near Medusa, a hamlet in southern Rensselaerville, where she says she can write in quiet.

Originally from London, Benedict’s first home in America was in California, then she moved to New York, where she is currently a professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. She wrote her first book in the United States, Bad Angel, about Dominican immigrants.

“I didn’t know how to write about comfortable Americans, even though that was most of the people I knew,” Benedict said, standing on the bright green grass of a backyard reception for authors. The lawn was strewn with people in conversations and holding small cups of wine, circled by women carrying trays of appetizers.

In her two most recent books, Benedict has written about the Iraq war, credited with breaking the story of military sexual assault there and inspiring the film Invisible War. Her most recent novel, Sand Queen, follows two women — one Iraqi, the other American — who meet at a prison checkpoint. It’s the first in a trilogy about rural white teenagers, between Rensselaerville and Slingerlands, who Benedict says are fed into the military.

Benedict favors non-fiction for its political messages and her novels for their ability to transport people and tap into readers’ empathy. She writes in diverse voices of men and women of different races. Every moment is research, she says, with “controlled day-dreaming” or holding a visual image of a character in her imagination.

Benedict listed the limits of non-fiction: ethical concerns of privacy, a subject’s limits on articulating or sharing his or her experience, and using real people in exploitative ways.

Her parents were anthropologists. “I spent a lot of my childhood being the new arrival or, sometimes, the only white person,” Benedict said.

Earlier that day, Benedict had interviewed Brooklyn-based filmmaker Hannah Weyer, who wrote the novel On the Come Up, and Anna Simpson, who inspired the book’s protagonist.

They told Benedict the book was a tool for teaching. Weyer leads media-arts classes and mentors teenagers in after-school programs in New York where she uses movies relevant to their lives.

Weyer was filming behind-the-scenes footage of Our Song — of the cast, crew, and neighborhood — when she first met Simpson. Simpson was changing her newborn daughter’s diaper on her chest, standing up, and Weyer kept filming.

“It’s not rags to riches, it’s about a journey out of her neighborhood, trying to create a stable environment for her newborn,” Weyer said of On the Come Up. The author said she was inspired by Simpson’s optimism and honesty, and gave those qualities to her character.

Through a series of recorded interviews, Weyer learned of Simpson’s story growing up in Far Rockaway, Queens that became the basis of the novel. The neighborhood is the final stop of the A-train subway line, which had been washed out by Hurricane Sandy.

“It has its little down parts but, for the most part, it was a little suburbish,” said Simpson, 30. She said she now works in a body shop and a Chrysler dealership and is working on an album of original music.

Simpson was eight months pregnant when she saw a poster in her high school advertising auditions for Our Song. Her mother had suffered a stroke and heart attack that left her disabled, Simpson said, and she became the adult of her home in her teens.

“You go where you feel comfortable,” Simpson said of her group of friends that drank and fought a lot. She was 13 and had befriended 18-year-olds.

Simpson traveled to her audition in Manhattan alone and was eventually cast in one of the lead roles. “I felt like it was an opportunity to get myself into something,” Simpson said of her work on the movie.

Race, class, and gender at the festival

After Walsh read from her book, What’s the Matter with White People?: Finding Our Way in the Next America, she sat with Winstead.

“I knew there was no post-racial America, but the amount of hatred was staggering to me…did you think it was deeper than I thought?” asked Winstead, who was the keynote speaker at last year’s festival.

Walsh, a political analyst for MSNBC, had described the limits of the story she and her father had told themselves about race in America during the civil rights era. The working-class white passion for the civil rights movement became fractured throughout the ensuing decades as, Walsh argued, liberals had allowed Republicans to churn a polarizing narrative of society’s underachievers taking government welfare and undermining the middle class.

While the election of a black president in 2008 happened sooner than expected, Walsh said, a conservative “backlash” of racism, in scrutinizing Barack Obama’s birthplace, for example, has been “terrifying.”

While introducing Walsh, Winstead asked, when people demand equality in the country, how does the power structure react? She turned the question to gender, saying that she has been called a “whore” by conservative twitter users.

“The one thing the Right knows is that the stories matter,” said Winstead, who launched a comedy tour in 2011 to benefit Planned Parenthood.

Carol Ash, the director of the Carey Center for Global Good, asked, from within the darkness of the crowd, “What are we to do in Rensselaerville, New York?”

“You go and get your family who watch Fox news out of the house,” Walsh said. People need to be engaged locally and more frequently than every four years, she added, and younger generations need to be reminded of the importance and value of voting.