Losses, lessons, and legacies

We take writing obituaries seriously. Often we write of people we know and love.

Unlike most newspapers, we don’t charge for obituaries. We consider the life of every person worth recording — to let the community know for now and to inform those who will be researching history later.

As we paged through our weekly newspaper editions for 2022, we were struck by how many obituaries appeared on our front page or were recognized in tributes on our editorial page.

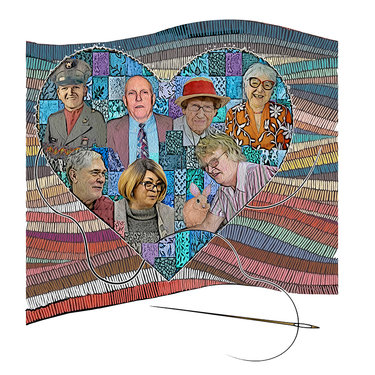

We have chosen seven of those people to write about here as we close out our year. Together, those seven people lived for 587 years — well over half a millennium. Surely, their deaths have left gaping holes in the lives of their families and those who loved them.

Their deaths were also a loss for our community at large. But, in reading about their lives for this year-end review, we felt more than loss. We felt comfort and joy.

Why?

Because each has left behind a legacy for the community. As you read their stories, maybe you will feel that comfort and joy, too.

And perhaps you will feel inspired, as we have, to learn from the way they lived their lives.

Our front page on March 17 featured the obituaries of two coaches — Jim Duncan and Arty Waugh — who had died earlier that month.

Voorheesville’s Jim Duncan was described by his longtime coaching colleague Joe Sapienza as a “community servant.” Raised on a dairy farm, Jim Duncan graduated from Voorheesville’s high school with the highlight of his 1966 senior year being part of the only undefeated football team in school history.

He coached a number of sports for Voorheesville and his daughter said he only ever missed seeing the school’s football games twice — because she and her sister had scheduled fall weddings.

Mr. Duncan got into coaching for the right reasons, said Mr. Sapienza: He wanted to have an impact on the lives of his players.

An Army veteran, he also volunteered for the Voorheesville Fire Department and loved his fellow firefighters like brothers, his daughters said, noting that community and caring for his neighbors was everything to him.

Arty Waugh, an art teacher at Guilderland, was a legendary coach who introduced lacrosse to Section 2. “He was so happy to be able to pass on that love and respect for the Native American game to a lot of young people,” said his wife.

Coach Waugh himself played as a lacrosse goalie until he was 60 and kept up with his own artwork after his retirement too.

“He always gave everything away,” said his wife. “He always thought, ‘What can I do to make a difference in somebody else’s life? What can I do to lift them up?’”

As he faced death in a hospital bed, Coach Waugh was flooded with text messages from his former students.

“You taught me probably the most important lesson about success … generally, you earn it by perseverance,” said one.

“With Coach, it was never a win-at-all-cost philosophy,” said another. “It was about making men who worked hard and did the right thing ….”

In May, Betty Spadaro died at the age of 103. She was a friendly and no-nonsense realist who never stopped caring about Altamont. “Doing things for others,” she said, was her motivation.

She started her teaching career at the one-room schoolhouse on the Bozenkill; continued it, teaching at Altamont High School; and, finally, after that school was demolished, taught in the then-new Altamont elementary School.

By her own description, she “stressed the basics along with emphasizing promptness, honesty, ambition, faithfulness, and organization.”

She was also involved in many community organizations: the Altamont Fair, the Order of the Eastern Star, the auxiliaries of the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars and the Altamont Fire Department, and she cared deeply about the village’s newspaper and library.

The library’s director, Joe Burke, said that last October Mrs. Spadaro had asked him what it would take to eliminate fines for overdue books. When he told her the amount the library had budgeted for fines in 2022, she said, “I can do that!”

And she did.

“To the end,” said Mr. Burke, “she wanted kids to have access to the library no matter their economic circumstances. I can’t think of a better legacy to have left this community that she loved so well and served so long.”

Also in May, Harold Miller, a man who had given Berne its history, died. The second eldest of nine children raised on a Berne dairy farm, he had deep roots in the Helderberg Hilltowns. He embraced his heritage and loved his hometown — yet felt he couldn’t live there.

We once asked him why he left. “Basically because I’m gay,” he answered in his usual straightforward fashion. “I didn’t feel comfortable. It wasn’t a great place to be gay.”

After graduating from Cornell and serving as a lieutenant in the Air Force, Mr. Miller worked for the National Park Service in Washington, D.C. There, he fell in love with Ed Davidson, who worked for the Smithsonian Institution.

The couple held a commitment ceremony on Dec. 31, 1967 but couldn’t marry until 40 years later when same-sex marriage became legal in Massachusetts. The Enterprise was pleased to run the couple’s wedding announcement, which caused several subscription cancellations as well as angry phone calls.

From afar, with the help of his brother, Ralph, Harold Miller pursued his boyhood love of local history. He started a website, now hosted by The Enterprise, dedicated to the genealogy of the Hilltowns and was instrumental in having Berne celebrate its history with a Heritage Day.

Mr. Miller carefully researched Helderberg Hilltown history and wrote books that corrected common misunderstandings. He also built up a network of people interested in assembling an association of Helderberg farmers and business owners that would act as a virtual chamber of commerce for the Hilltowns; the Helderberg Hilltowns Association still leads events.

In short, Mr. Miller extended our idea of community. Although he felt he couldn’t comfortably live in the Hilltowns, he was buried there.

In July, Beverly Ann Bardequez died. She was fiercely proud of the Rapp Road community where she was born and where she lived her final years — fighting to protect her community for future generations.

She loved to recall the joys of her childhood living near her grandparents in a part of Guilderland that was carved out the pine bush in the 1930s by African-American sharecroppers who came north during the Great Migration.

She remembered how her mother, her grandmother, and her aunts were “always doing projects” — one of which was making a manger scene in the front yard at Christmastime. “I can still smell the scent of pine boughs they used to make the roof of the manger,” she said.

Ms. Bardequez also said, “It didn’t matter whose child you were, from one end of the road to the other, you were treated like you belong.”

She came to appreciate the industriousness of the women she knew. “It started to occur to me, they will tackle anything, they will build anything, and they’ve passed that down.”

What Ms. Bardequez built — one lecture at a time, educating people about her community; one meeting at a time, explaining to planning boards why developers shouldn’t be allowed to obliterate her neighborhood — was pride in the Rapp Road community.

“Every house on this road was built by hand by the wonders, and each one had some strength that they could lend to help,” she said, stressing, “It was their determination to survive and work together that helped this community stay intact all these years.”

Ms. Bardequez also said, “I believe God brought me here because he knew that, in order for us to keep what was formed here, what was born here, someone had to pick up the mantle. And I’m hoping to pass it on to the next generation.”

In September, Jan Van Etten, a Knox farm wife, died. She used common sense for the common good.

She was born during the Great Depression and raised in an era when a woman’s sphere was the home — being a helpmate to her husband, raising their children, and contributing to the church and community as a volunteer.

Mrs. Van Etten fulfilled all those roles — but in her own way. She drove the tractor on the farm she and her husband owned; she raised Flemish rabbits that were ranked first in the nation; she planted Christmas trees that made her farm a mecca for visitors who relished the country experience of fetching a tree, complete with hot cocoa and wagon rides.

As president of the Kiwanis club one year, Mrs. Van Etten wrote us a letter about the Memorial Day parade with the theme “Honoring our Heroes.”

“When I thought of all the heroes we have,” she wrote, “I honor our boys who go to far-off lands to keep us safe. I think of the heroes who drove the ambulance that came when I called to take my husband to the hospital.

“I have lived in these mountains for almost 50 years and the Knox firemen have saved my home twice when the chimney caught fire. America is great because neighbors come to the aid of their neighbors.”

Her idea of helping neighbors extended far beyond the Hilltowns. For years she headed up the local Fresh Air program, settling kids from New York City for the summer in country homes, including her own.

Mrs.Van Etten took up the project after enduring perhaps the worst fate a mother can suffer — the death of her child. “Our first little boy died, and I missed having a little guy around,” she said

In short, Mrs. Van Etten turned her horrible personal loss into something good for others.

Later in September, Hedi McKinley died at the age of 102. She had endured immense hardship in her long life and yet considered herself lucky.

She was thrown out of her childhood home in Vienna by Nazis, and later buried three beloved husbands yet she still had a clear-eyed love of life — and of helping others.

A social worker, professor, and author, Ms. McKinley was well known locally for the practical and insightful advice she gave on local radio and television stations and as a columnist for The Altamont Enterprise.

“I always wanted to come to America,” she said. “It seemed to be unfettered and open to the kind of person I was.”

After graduating from Columbia University while supporting herself as a waitress, she decided on social work for a career, Ms. McKinley said, because she “wanted to make the world better. You can help a lot of people in social work. Especially in this country, I wanted to give back; I felt grateful.”

When she first came to America, Ms. McKinley refused to speak or read German. “I was too traumatized,” she said.

Although it was difficult for her, Ms. McKinley in her later years frequently talked to school groups about her Holocaust experiences.

Why? “It is so easy to slide into catastrophe. It is so easy to feel that your neighbor, who is different, is a bunch of garbage and you have a right to dump him into the garbage can,” she said.

“The way Hitler took over Austria, Austria lay down,” Ms. McKinley said, stressing that it is easy to scapegoat and she doesn’t want that to happen again.

Ms. McKinley wrote in her memoir, “Stories From My Lucky Life”: “My life philosophy is unsentimental. Live peacefully and gratefully. Teach your children to not hurt others. Be kind.”

A common thread in the lives of these seven people is that they cared about others — teaching life lessons on the playing field or in the classroom, uncovering and sharing a sometimes difficult history, keeping a worthwhile neighborhood intact, understanding the worth of looking out for one another, and telling hard truths to save others.

If we learn from these legacies, they will live on.