A man with a mission: Tim Albright succeeds in having Thacher Park recognized as a National Natural Landmark

One man’s lifelong reverence for John Boyd Thacher State Park has resulted in a designation that will perhaps spread that reverence nationwide.

This week, the National Park Service named Thacher Park as a National Natural Landmark.

We heard the news on Wednesday — the day before the press release came out — when we got a call from Tim Albright.

Albright spent thirty years working towards this designation for the park.

Now nearly 63, he said, “I wondered if I’d live long enough to see it through.”

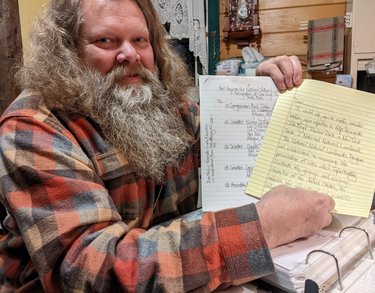

We went immediately to Albright’s New Scotland home at the base of the escarpment where we sat at his kitchen table as he leafed through a three-inch thick binder that meticulously mapped his quest for the designation.

Albright grew up at the foot of the Helderbergs. He and his brother, Chris, hiked there as boys and know the terrain intimately. Both are also deeply knowledgeable about the history of the area and have worked to preserve it.

At age 13, Tim Albright entered a contest held by the New Scotland Historical Association to design a seal for the town. His entry won and is still used by New Scotland.

As an adult, Albright worked at and came to manage Indian Ladder Farms, which runs along the base of the escarpment. He also assumed a leadership role in the historical association. He and his wife, Susan, are lifetime members.

In the 1990s, when he was in his thirties, Albright started his quest to have Thacher Park recognized.

He started out seeking an historic designation through the state.

The earliest letter in Albright’s voluminous binder is dated Nov. 24, 1992. Written to a field representative of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, the letter was pounded out on a typewriter — five full pages of single-spaced text.

Albright was writing as the head of New Scotland Historic Preservation Committee. The letter quotes from the 1869 Harper’s account written by “famed Verplanck Colvin, geologist, explorer, and topographer.”

“What is this Indian Ladder so often mentioned?” asked Colvin. “In 1710, this Helderberg region was a wilderness: nay all westward of the Hudson River Settlement was unknown. Albany was a frontier town …. Straight as the wild bee or the crow the wild Indian made his course from the white man’s settlement to his own home in the beauteous Schoharie Valley. The stern cliffs of these hills opposed his progress; his hatchet fells a tree against them, the stumps of the branches which he trimmed away formed the rounds of the Indian Ladder.”

Colvin also remarks that a large vein of iron pyrite at what is now Thacher Park may have been mined by prehistoric man.

Colvin goes on to report on the “Tory House,” a cave on the trail “reputed as being a meeting place and asylum for England’s cause. John Salisbury, a British spy, was tracked here and captured at the time of Burgoyne’s campaign, which ended in 1777.”

Albright writes that anti-renters in the Helderbergs challenging Patroon Van Rensselaer used what is now known as Hailes’ Cave as a hideout.

Albright goes on to write of the “world-class scientists” who have visited Thacher Park. “They have come from France, Switzerland, and from many states, colleges and museums in this country,” he wrote.

He writes, too, of how the land became a park when, in 1914, Emma Treadwell Thacher, the widow of John Boyd Thacher, a state senator and Albany mayor, donated 350 acres to the state for parkland.

Albright quotes from an address given at the dedication ceremony: “Keats’ memorable line — ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever’ — was never more clearly and beautifully typified than in this wonderful mountain escarpment. It has always been a thing of beauty; time will only improve but not detract from it. We may well say that the time has come and time has gone, but this park will stay here forever.”

The “forever” nature of Thacher’s beauty was threatened, as Albright reported in 1992, with two proposals — building a hydroelectric facility there or using it as a regional landfill.

The land that Emma Treadwell Thacher donated was known as Indian Ladder Park even though it had been privately owned. At the time she donated it, Albright said, the park had several colonial homes as well as a 1767 Dutch stone house and a stone watchtower, which was used during World War II to test lights across the valley.

Doing research at the New York City Public Library, Albright found a letter of complaint written in 1916 by the park’s first superintendent, John Cook, who had lived in one of the old farmhouses. He was isolated in the winter, all by himself; even the peddlers couldn’t get in, said Albright.

Unfortunately, Albright said, the historic structures were torn down. So, on advice from New York Parks, he soon shifted his efforts toward seeking a National Natural Landmarks designation.

On July 15, 1994, he wrote to a representative of that program another long, type-written letter, describing the escarpment as “abundant in exposures and landforms that record active geologic processes or portions of earth’s history, and fossil evidence of biological evolution.”

The representative responded that she had reviewed the materials Albright sent and agreed “this is a very interesting geological feature worthy of further review.” She advised, “The evaluation must be completed by a qualified researcher.”

Albright gathered letters of support from a wide range of geology professors whose classes visited Thacher Park.

“Many generations of geologists and their students have studied the area, beginning in the early 1800s with the likes of … James Hall, State Paleontologist of New York,” wrote a Williams College professor, Markes E. Johnson, in 1995. In addition to bringing his own students to Thacher, Johnson wrote, “I have also conducted world experts on carbonate systems to this locality, including visitors from China and Russia.”

“The wonderfully fossiliferous limestones of the Helderberg Group exposed at and around Thacher Park are the place where investigations of the Devonian strata of North America were first begun,” wrote the head of the geology department at the University at Albany, W.S.F. Kidd, “in the mid-nineteenth century by geologists who were among the most distinguished of their time.”

Hydrogeologist Kevin J. Phelan agreed to take on the task of applying for the designation.

He wrote to Albright that he had grown up going to family picnics at Thacher Park and, as an undergraduate, was inspired to pursue a career in geology when he read Dr. Winifred Goldring’s guide to the geology of Thacher Park, published by New York State Museum.

Unfortunately, Albright said, the Park Service put a moratorium on its National Natural Landmark program so Phelan’s work was not completed. The application languished until 2012 when Salim Chisti with that state’s Parks office wrote that, while developing a master plan for Thacher Park, his team had come across the application.

“The file indicates that this application was approved and a memo to that effect was signed by then Commissioner Castro,” Chisti wrote to Albright of Bernadette Castro, the former Parks commissioner. “Unfortunately, the record ends there, with no indication if this was followed up on with NPS.”

By 2014, Chisti reported that the National Parks representative for the Northeast visited Thacher and was “floored by how prevalent and visible the fossils are” and was also impressed by the visible aspect of the escarpment.

Albright once again picked up his pen. On the same yellow legal pads that he uses to write, by hand, letters to the Enterprise editor, he wrote out lists of state and federal politicians that people in support of the designation could write to.

In his distinctive, artistic script, Albright wrote a four-page sample letter to inspire supporters. His sample letter, after extolling the worth of Thacher Park’s geologic history, ends with thanks “for the time you spend helping our country be great.”

We are happy to tell this story of an individual making a difference — a positive change that benefits all of us.

Because Tim Albright is a humble man, he credits the many people who helped in the quest.

But, on looking through his binder, we see how, year after year, letter after letter, he persevered and brought others along in the quest.

This story is also about the power of words — one man with a pen, and a typewriter, persistently and patiently, always with graciousness, reached out to state and federal officials, to government representatives, to scientists, and more.

The history of Indian Ladder is all around Tim Albright — in objects as well as ideas. He has a century-old Indian Ladder pennant on the wall of his home along with Helderberg paintings, and countless postcards picturing the park over decades — including one showing a waterfall that was lost when water was rerouted for a parking lot.

On our recent visit, he reached down from a shelf a pair of birch-bark napkin rings, Indian Ladder souvenirs from 1912.

Albright never gave up as he skillfully threaded his way through layers of bureaucracy to get a Natural Landmarks designation for Thacher Park.

Much as the Native Americans were not stopped in their travels by the sheer escarpment cliffs, he found a way to build a ladder to reach his goal. The rest of us should follow in his footsteps.