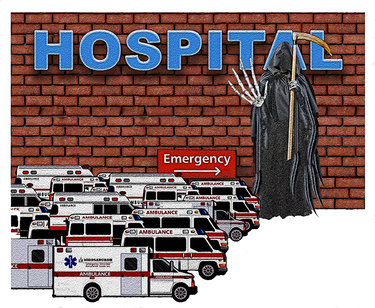

Life and death in the parking lot: Hospitals must respond

Hospitals are often understaffed. This is a nationwide problem as well as a local problem. It’s not a new problem but it was heightened by the pandemic.

Readers of The Enterprise called us after we ran a letter in October 2021 from Mark W. O’Brien of Clarksville, “The Twilight zone plays out in a hospital emergency room,” to see if it was a parody or real.

“Your wife might call 911 and you then take a ride in an ambulance to the hospital …,” O’Brien wrote. “Your ambulance may be told to hold in the parking lot, effectively turning your gurney into an emergency-room bed …. You might be so dehydrated they stick you repeatedly and still not create a good intravenous connection.

“Then, to get a blood sample, they may suction out blood, with a single-use syringe that pulls the blood out. You’re conscious, so you can feel it being pulled from everywhere in your body and through your arm as if it were a pneumatic straw.”

Finally admitted to the emergency room, O’Brien had a long, painful and fruitless wait before he ultimately called his wife to set him free. “You have to help get me out of here!” he told her. “Listen to me, please, please, come get me!”

When we called O’Brien to confirm the letter and learned it was not satire but his honest view of what he experienced, we found out he had gotten an appointment with his cardiologist for needed medical attention.

More recently, John R. Williams, who writes our weekly Old Men of the Mountain column, described his own hospital experience after the Old Men’s Sept. 6 breakfast at Mrs. K’s in Middleburgh. He became wobbly and kept feeling worse so an ambulance was called. The emergency drop-off at the hospital was backed up with ambulances.

“It was raining as the ambulance from Middleburgh unloaded the OF in the rain, out on the drive. Great way to start. Inside … the gurneys from the ambulances were lined up in the hallway in the order they arrived at the emergency room. It was quite a while before the Middleburgh group was first in line.”

Williams then spent 12 hours on a gurney in the hospital hallway. The next morning he was given a CT scan and told he had blood clots on his lungs, the result of having had COVID-19.

We knew from talking to volunteers with the Berne Ambulance squad in the furthest reaches of our coverage area, the Helderberg Hilltowns, that waiting for hours to have a patient transferred from an ambulance to an emergency room is not unusual.

So we were pleased last month to break the story about a proposal pitched by Jay Tyler, director of the Guilderland Emergency Medical Services, that the town board, after some fine-tuning, unanimously adopted on Nov. 15.

Tyler made a compelling case, stressing that sometimes his crews are delayed at hospitals for an hour up to four hours.

“They’re really holding us hostage there,” he said. “We have to treat the patient; we have to monitor the patient.”

This means that, if other residents call in with emergencies, they may not quickly get the help they need. Even crews from neighboring towns, which typically cover for each other when needed, Tyler said, may be similarly tied up, waiting at hospitals.

“We’ll travel with lights and sirens to the hospital only to be told to wait on the ramp and treat the patient …,” said Tyler. “Sometimes they’re treating the patient for hours and hours,” he said of his crews.

The waiting time for Guilderland crews has more than doubled in the last three years, as have the costs.

The cost to the waiting patients is incalculable.

The new Guilderland policy sets out three levels, each with a shorter waiting time based on availability of ambulance crews:

— Condition Green has a 45-minute maximum wait and applies when the majority of ambulances, two to five, and their crews and equipment are available for the next emergency call;

— Condition Yellow has a 30-minute maximum wait and applies when the number of available ambulances drops to one or two due to more calls or longer hospital delays.

“This is when the medical need begins to tax the system, yet things are not absolutely critical,” the policy says. “Response times have increased to 1 ½ to twice normal response time.”

In rural areas, the policy notes, Condition Yellow is reached “fairly rapidly because of limited resources available; and

— Condition Red says “all offloads will be immediate” and has a 10-minute maximum. Red is reached when no ambulances are available in town.

In each of the levels, the policy states, that, at set intervals, the EMS crew will apprise the charge nurse or triage nurse of the ticking time frame and will also let the GEMS Communication Center know of the delays. EMS crew members are advised to take their radios inside the hospital with them to stay aware of changes.

This policy should serve as a model for others.

Tyler chairs the EMS Patient Offload and Delay Committee, which is looking at the problem regionally, and says most local EMS agencies aren’t owned by a municipality, like GEMS, but rather are commercial services or not-for-profits, like Helderberg Ambulance.

It is crucial for hospitals to work with emergency medical services to shorten wait times.

Federal law makes the hospital responsible for a patient once an ambulance reaches hospital property, and EMS remaining with the patient is voluntary.

Tyler said he has tried repeatedly to reach local hospital leaders and gotten no response. “There’s been no communication with me …,” he told the Guilderland Town Board on Nov. 15, weeks after news was reported on the policy. “I will keep on attempting to contact and collaborate with the hospitals to try to manage the program and implement it … I’ve reached out multiple times … I will continue to try.”

He also said, “As the days go by, I’m less and less optimistic.”

This is simply unacceptable. Hospitals are legally responsible for patients arriving on their grounds. Are they waiting for lawsuits to force action they should be taking preemptively?

Certainly, hospitals have much larger problems to solve with their lack of staffing but simply ignoring requests to discuss Guilderland’s EMS plan is counterproductive. Hospitals cannot simply treat EMS workers as unpaid staff.

In 2006, the federal Government Accountability Office studied hospital wait times since more than 40 percent of emergency-department visits were paid for by federally-supported programs. Even back then, GAO found the average wait time to see a physician for emergency patients — those patients who should be seen in 1 to 14 minutes — was 37 minutes, more than twice as long as recommended for their level of urgency.

The report used ambulance diversion and patients leaving the emergency department without being seen as proxy measures for treatment delays. Waiting for an open emergency-department bed compounds problems for hospitals and patients, the analysis found. Administration of medication is delayed and there is a failure to meet standards of care for treatments such as antibiotics for sepsis.

Delays in patient throughput in the emergency department decreases hospital cost efficacy and increases subsequent hospital stays — both of which are of concern to hospitals and have negative financial impact, the report found.

So it is in a hospital’s own self-interest to deal with this problem.

Finally and most importantly, the Government Accountability Office found factors of diversion status — sending ambulances to other hospitals — and emergency-department boarding — keeping patients on ambulances waiting — both have been linked to increases in patient morbidity and mortality.

Long ambulance wait times are literally a matter of life and death.

A paper published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine and also posted to the National Library of Medicine details ways that prolonged-emergency department wait times and lengths of visits reduce quality of care and increase adverse events.

“Emergency department (ED) crowding in the United States has become so severe that the Institute of Medicine calls it a ‘national epidemic,’” the report said. “Across the nation, an ambulance is diverted away from an overcrowded ED approximately once every minute. Patients who do arrive in the ED have faced increasingly long average wait times and ED visit lengths over the past decade. Most importantly, these increases have been most pronounced for patients with the most acute illnesses.”

The report goes over a wide range of institutional practices that hospitals need to improve involving triage, registration, patient flow, physical environment, laboratory testing, admission processes and policies, workload assignment, staffing, and others.

Tyler concluded his initial presentation to the Guilderland Town Board by saying “It’s not EMS against the hospitals. We understand hospitals have issues there,” which he believes “need legislative remedies.”

But, in the meantime, as hospitals wait for, say, the limited number of nursing students that have recently been given state scholarships to graduate, and other more substantive remedies, they have an obligation now — without further delay — to answer Tyler’s calls and work collaboratively with local EMS crews to solve the problem of ambulance wait times.

During the pandemic, we had a sense of medical professionals pulling together. Area hospitals held over a half-dozen joint press conferences to inform the public of their progress.

At one of those, in December 2021, Dennis McKenna, president and chief executive officer of Albany Medical Center, stressed that the region’s hospitals are using “preparation over panic, cooperation and collaboration over competition.”

That philosophy of cooperation should be ongoing and should include emergency medical services.

A year later, in December 2021, St. Peter’s Health Partners Chief Medical Director of Acute Care Thea Dalfino made a plea to the public that injured and sick people who are not in critical condition go to clinics, urgent-care centers, or their own doctors’ offices for care.

“We’re being overrun right now in our emergency departments …,” said Dalfino. “Our emergency departments really are for the sickest patients.”

This is still good advice.

But, for those who truly need an ambulance, we have to make sure they are available. Hospitals must — right now — work with EMS leaders to come up with workable offload plans.

“At the end of the day, if the patient’s critical, we’ll end up waiting …,” said Tyler. “We’re not going to abandon a patient.”

But what if someone else is dying because no ambulance is available?