A wing – and a prayer

It’s time we had a talk about the birds and bees.

That was a euphemism used by generations of parents to tell their children about “the facts of life.”

The subject we’re referring to, though, is about more than procreation — it’s about the very survival of life as we know it on our planet. We’ve written about the bees in this space, outlining their decline and praising measures to sustain them.

Now it’s time for a similar theme for the birds. The hubris of humanity leaves us dumbfounded.

It’s autumn, and we scan the skies looking for the ragged Vs of geese heading south for the winter. The sight seems more rare than in our childhood. Is it our imagination?

No.

Where are the overhead calls of the honking geese? Is this the silent fall that follows Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring?”

Perhaps.

Last week, a stunning report was published in the journal “Science” that integrated wide-range bird population trajectories and size estimates to discover that, in the last half century, North America has lost 29 percent of its birds.

The report estimates a net loss approaching 3 billion birds.

The scientists confirmed their numbers by looking at a continent-wide radar network that also shows “a similarly steep decline in biomass passage of migrating birds over a recent 10-year period.”

The report goes on, “This loss of bird abundance signals an urgent need to address threats to avert future avifaunal collapse and associated loss of ecosystem integrity, function, and services.”

The report notes, “Because birds are conspicuous and easy to identify and count, reliable records of their occurrence have been gathered over many decades in many parts of the world.”

We got news of just such a record last week. In a letter we look forward to annually, Will Aubrey reported on the Helderberg Escarpment Hawk Watch at Thacher Park. We’re printing Aubrey’s letter, with one of several pictures he sent of individual birds that are part of the diurnal raptor migration. The picture we selected to print, taken by Luciano Toffolo, is of a golden eagle.

We could hear the excitement in Aubrey’s voice when he described the sighting of this eagle — “rare — the best I ever saw,” he said.

Toffolo had taken a picture of a bald eagle, too. The salvation of the bald eagle, our nation’s symbol, is an environmental success story.

For much of the 20th Century, the bald eagle population was in decline and, by the late 1900s, was near extinction in the continental United States. While there were as many as a half-million bald eagles in North America in the 18th Century, by the 1950s, there were just 412 nesting pairs left in the contiguous 48 states, according to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute.

The pesticide DDT had affected the eagle’s calcium metabolism, making males sterile and females unable to lay healthy eggs — the eggshells were too brittle not to crack under the weight of a brooding adult.

At the same time, bald eagles were being hunted and their habitat was disappearing. In 1940, Congress passed an act to protect both the bald eagle and the golden eagle.

Still, by 1967, the bald eagle was declared an endangered species. What saved the eagle was the banning of DDT in 1972. Today, there are an estimated 10,000 breeding pairs.

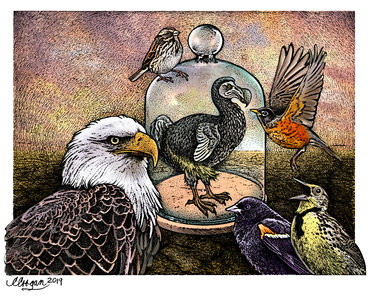

But, while our society is largely aware of species on the endangered list or species going extinct, what is remarkable and horrifying about the recent “Science” report is that it shows declines are not restricted to rare and threatened species.

Rather, those species that had been considered common and widespread are also diminished. The survey covers over 500 species and shows birds we may take for granted, like blackbirds and sparrows or robins and warblers, are also declining.

Common birds like these are quietly essential to ecosystems as they spread seeds, pollinate, and control pests.

The report’s abstract states, “Species extinctions have defined the global biodiversity crisis, but extinction begins with loss in abundance of individuals that can result in compositional and functional changes of ecosystems.”

It’s not just people like Will Aubrey, birdwatchers with binoculars, who should care about this. It’s something all of us need to care about and act on.

As the report says, “These results have major implications for ecosystem integrity, the conservation of wildlife more broadly, and policies associated with the protection of birds and native ecosystems on which they depend.”

Likely causes are, again, loss of habitat and pesticides.

What can we do to help reverse the downslide of bird populations?

As citizens of the United States, we can demand that the current administration not roll back the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which protects birds from people.

The Audubon Society points out, correctly, that many of the threats birds face today — like oil spills and communication towers — are new. These kinds of deaths are called “incidental takes” and the Trump administration is saying industries will no longer be held responsible for “incidental” bird deaths.

The Audubon Society estimates that power lines alone kill 64 million birds a year. The law, as it was formerly interpreted, was a tool to get industries to take the steps needed to protect birds, which the Audubon Society says are simple and cheap.

Meanwhile, the Audubon Society offers steps that individuals can take if our government won’t regulate harmful pesticides or maintain a treaty that has been effective for over a century.

Some of the steps include making your yard an oasis for birds with native plans and clean water, becoming a citizen scientist taking part in the sorts of counts that led to the recent discovery of bird population declines.

You can work with neighbors or your town or village to create places for birds to thrive, you can forgo pesticides and bright nighttime lights. You can buy grass-fed beef, part with plastics, and cut carbon emissions. You can keep your cats inside and advocate for a species you like.

If we, as a nation, could save our national symbol, there is still hope. The time to act is now.