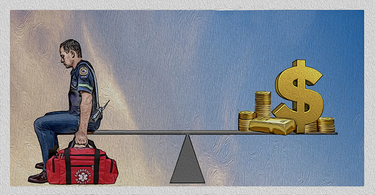

Emergency medical services should be paid directly, the governor must sign the bill that would make that law

Ambulance workers have tough jobs.

Some days, they must feel as if they are in a war zone. Their actions can mean the difference between life and death.

For the person who calls an ambulance, whatever they are going through is often a once-in-a-lifetime experience. For the crew that responds, while it may never be routine, dealing with a heart attack, or a car crash is a regular occurrence.

Some stories stay with you. For us, such a story was the death a quarter of a century ago of a young Guilderland emergency medical technician. David Squires took his own life in 1998.

His family held a memorial service in Guilderland Town Hall where members of his squad spoke openly about both the satisfaction and horrors of the work they did, day in and day out.

Squires had served on the Western Turnpike Rescue Squad which was made up both of paid professionals, like himself, and trained volunteers. Squires was just 24 years old.

His colleagues described a vibrant young man who loved hiking and mountain biking; a sensitive young man who cared deeply about the people he helped — and those he couldn’t help.

He was credited with helping a young woman’s heart to start beating again, and with helping an elderly man’s breathing to resume. Those were the good calls, where lives could be saved.

But he was also on calls where the victims were beyond help.

Richard Beebe, Squires’s first crew chief with Western Turnpike, which Squires had joined in 1995, described two difficult calls in January 1998, the month before Squires’s death.

In the first, a driver, allegedly drunk, struck and killed a 21-year-old man walking on Gipp Road; Squires was the first on the scene and the last person the victim saw before he died.

In the second, a year-old baby boy died of heart failure and Squires couldn’t forget the baby’s “blue eyes looking up at him as he was intubating him,” Richard Beebe said at that long-ago memorial service.

The pastor who worked with the squad said, “David was at home on the rescue squad because his very core was service.”

We’ll never be able to fully compensate for that kind of service but one practical thing we can do is to make sure members of ambulance squads are paid a living wage.

For decades, Guilderland was covered by two volunteer squads — Western Turnpike and Altamont. As volunteers became harder to find and training for first responders became more advanced, paid workers were added to the squads.

In June 2018, the Guilderland Town Board voted unanimously — with no previous public discussion — to establish its own ambulance service and hire enough emergency medical technicians to staff the ambulance 24 hours a day.

Last week, in presenting Guilderland’s tentative $45 million budget for 2024, Supervisor Peter Barber said Guilderland Emergency Medical Services is “almost a $4 million operation.” He noted that, for funding, it relies on property taxes as well as money from Medicare, Medicaid, and insurance companies.

We agree with his statement, “It’s well worth it for the quality and service and advanced life support that it provides.”

The future of the Altamont Rescue Squad is now in question after a policy change implemented by GEMS earlier this year, which decreased Altamont’s transports by 70 percent, according to the squad’s director of operations. Our reporter Noah Zweifel thoroughly described this new policy in a recent front-page story.

In addition to subsidies from the municipalities it serves, the Altamont squad, too, makes money by billing the insurance companies of people the squad transports to hospitals in their ambulances.

The Altamont squad provides only basic life support, administered by an EMT for procedures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR, and bleeding control while GEMS provides advanced life support, too, administered by a paramedic, including medical procedures such as installing IVs, administering medications, and intubating patients.

Both of these services as well as the service supplied by the county sheriff’s EMS to many of the Hilltowns would benefit from direct pay by insurance companies.

The current system relies on insured patients, once they are paid for ambulance services by their insurance companies, to, in turn, pay the ambulance squad.

Often, this doesn’t happen.

GEMS Director Jay Tyler told Zweifel that Guilderland doesn’t use aggressive practices that people associate with hard-billing. “We have a collection agency that makes phone calls. That’s about all they do,” he said. “Nobody has ever gone to collections, nobody’s credit has ever been hurt.”

The reason Guilderland uses a collection agency, Tyler explained, is that many patients keep the checks that their insurance agency sends them for the ambulance expenses. For those who genuinely can’t afford it, the town has a hardship program in place.

“In an agency like ours that does 7,000 calls a year, you see it more than you can imagine … and there’s not much we can do about it,” Tyler said of patients keeping money from their insurance companies.

“If you look at some of these folks that take ambulance trips once a month, and they start to take more and more ambulance trips closer to Christmas, it’s a little bit curious, and they don’t remit the bill to us,” Tyler said. “That’s where the collection agency actually came in. It’s for those folks. It was never designed to harm or dissuade elderly folks or folks who can’t afford EMS.”

Tyler also said it’s “crucial to emphasize that no one should hesitate to dial 9-1-1 due to financial worries.”

We are in full support of the direct-pay bill, which passed unanimously in both the Assembly and the Senate this year. A history of the bill shows that a version of it has been introduced in both houses every year since 2009.

Quite simply, it would authorize insurance companies to pay ambulance services directly.

It’s high time Governor Kathy Hochul signed direct-pay for ambulance services into law. It will help public and private; volunteer and professional; rural, suburban, and urban ambulance services get the funds they are entitled to.

It will keep people who are abusing the current system — with multiple unnecessary calls to pay for Christmas shopping — from doing so while freeing up ambulance workers to tend to people who truly need their services.

It will also simplify the process for people who are confused, as often happens in a medical crisis with so many bills coming in, and don’t get the money they owe to the squad. These patients aren’t intentionally abusing the system; they merely lack the wherewithal to follow through.

There won’t be any added costs. The insurance companies will still be paying the same amount for the same services; if the direct-pay bill is enacted into law, it will simply guarantee that the provider of the service is paid for it.

A more direct system is more efficient. Services like Guilderland’s won’t have to waste money on a collection agency trying to round up funds that rightfully should go to the ambulance workers.

That saves taxpayers money, too, because they won’t have to make up the cost for ambulance services called by scammers or for bills unpaid by confused patients.

To begin where we started, those who work on the front lines as David Squires did deserve a living wage. A direct-pay law will help with that.