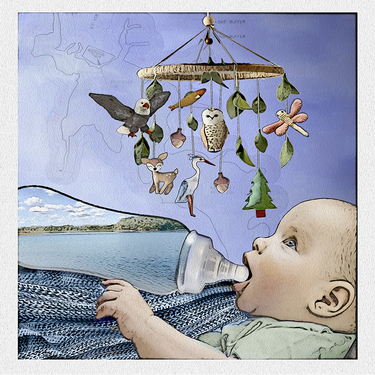

Look to the future: Take a baby step by buying land to protect our reservoir

Water is essential to life.

We commend the Guilderland Zoning Board for making the right decision on Oct. 4, denying a variance request that would have allowed a developer to build a contractor yard with storage warehouses within the 500-foot setback to the Watervliet Reservoir.

The board’s vote denying the variance was unanimous. Chairwoman Elizabeth Lott gave a cogent summary of the motion for denial “based on this board’s analysis of the materials and applying the law to the facts.”

Lott noted there “would be a huge change in the character of the neighborhood”; the applicant acknowledged the difficulty was self-created; the “sole source of the town’s drinking water” would be subject to contamination should an accident occur; and, “weighing the benefit to the applicant against the detriment to the health, safety, and welfare of the neighborhood or community … we found that it would be extremely detrimental or at least potentially detrimental.”

The unanimous vote to deny the variance followed a public hearing in which 20 people spoke against the plan; the zoning board also received 15 letters opposed to the project.

The speakers, united in their passion to protect the purity of the reservoir water, came from both Watervliet and Guilderland.

The reservoir had been built by Watervliet after typhoid became a health issue for the city at the start of the 20th Century. Six-hundred acres of Guilderland farmland were flooded by damming the Normanskill.

The reservoir is currently Guilderland’s major source of drinking water.

A map displayed at the hearing showed the reservoir and the two different buffers that had been set up to protect it — a red line delineates a 300-foot buffer and a blue line marks a 500-foot buffer.

Michael Floccuzio wanted to build seven warehouses, totalling 56,400 square feet, on the 10.7 acres he’d bought in the Rural Agricultural district at the corner of routes 20 and 158.

His engineer, David Kimmer with ABD Engineers, told the board traffic should be minimal, no hazardous materials would be stored on site, and there would be no water connections or septic systems. Kimmer noted that a special-use permit would be needed later for a contractor yard but the current variance request was because Floccuzio wanted to build within the 500-foot setback.

Kimmer said the plan would abide by the 300-foot setback adopted over a century ago and noted over 50 structures within the 500-foot setback already.

The 500-foot setback, Kimmer said, “effectively renders the site unbuildable.”

Under questioning from zoning board member Sharon Cupoli, Floccuzio said there would be 33,000 square feet of pavement. He also revealed there would be no system for checking what was being placed in what he termed the “glorified” storage facilities.

Several officials from Watervliet — the mayor, the city’s general manager, and two council members — were on hand at the public hearing, making the point that the benefit the applicant would receive from the variance would not outweigh the burden of health, safety, and welfare of the public.

But Lois Gundrum, a former Earth science teacher, who described herself as “just a resident” of Watervliet, contrasting herself with the officials, may have said it best.

“I am a blue-line person, and I’m here to ask that you honor the blue line,” she said. “I’m concerned about the quality of my drinking water and the drinking water of the people that live in my city. I also feel that Guilderland residents need to be protected.”

Several Guilderland residents who spoke later took her cue and called themselves blue-liners.

One of them was long-time Guilderland teacher Jennifer Ford who lives just a quarter-mile from the proposed site. She became tearful when she said, “All my students drink that water.”

We should all be blue-liners.

We should each see the importance of protecting our water sources.

Now that the zoning board made the right call, protecting an essential resource, the question becomes: What next?

One solution for this particular parcel may lie in the comments made at the public hearing. Many of the speakers lauded the beauty of the parcel, where they watch eagles and egrets, as well as the importance of its history.

“I’m a Sharp from Sharps Corners and that property belonged to my father’s cousin, who we called Uncle Walter and I’ve had happy memories of that property,” said 80-year-old Diane Sharp Stedman.

Her concern, she told the board, was the historic cemetery and the graves on the other side of the iron cemetery fence. “My great-grandmother and grandfather are buried there, along with Gilbert Sharp, who is believed to have been a Revolutionary War soldier,” she said. “And I want to protect that cemetery.”

Gilbert Sharp served in Albany County’s 7th Regiment during the Revolutionary War and was deeded a parcel of 161 acres along the Normanskill in 1801.

Guilderland resident John Haluska in his characteristically fiery fashion said that Floccuzio had purchased the property on Groundhog Day for $80,000 — well below the usual price for a parcel that size in Guilderland.

“This is a crapshoot in Las Vegas,” said Haluska, stating Floccuzio was trying to use “hocus pocus” to “get us from a blue line to a red line.”

Since that gamble failed, it may give the town a chance to purchase the property — perhaps with Watervliet chipping in — to protect the municipalities’ shared water source while, at the same time, offering Guilderland residents a natural respite in the midst of the rapidly-developing suburb.

The current assessment roll lists the 10.5-acre property as having a full-market value of $76,471.

We’ve written on this page many times that, while it’s important to protect our resources, municipalities cannot afford to buy them all. This one may well be an exception.

Flocuzzio could recoup his investment and build in an industrial zone where his project belongs as several of the speakers noted at the public hearing.

As we’ve seen here, wise zoning interpreted by a competent board offers some protections. As Flocuzzio’s engineer himself said, the 500-foot setback “effectively renders the site unbuildable.”

We’ve seen this elsewhere in Guilderland, with the recently condemned Rustic Barn complex at 4852 Western Turnpike.

“Due to the setbacks required from Route 20 and the adjoining wetlands on both sides that feed the Watervliet Reservoir, no building can be constructed on the premises,” a neighbor who was long interested in buying the property told us. “The only thing that can be done is to demolish the structure and plant some flowers.”

Guilderland is currently in the process of updating its two-decades-old comprehensive land-use plan — on which zoning is ultimately based — giving the town a perfect opportunity to ensure the protection of water sources.

Meanwhile, looking at the bigger picture, the Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy continues to try to add to the Bozen Kill Corridor, protecting a stream that feeds the Watervliet Reservoir.

As always on this page, we urge people to contribute to the conservancy’s efforts. Yes, it helps protect our water. But, in this era of drastic climate change, it also protects habitats for a wide variety of species and helps in abating climate change itself.

The town of Guilderland, too, is looking at the big picture and has set up a conservation easement program such that the town’s tax burden on a property is reduced depending on the length of time a property owner commits to leaving the land undeveloped.

A committee was set up in Guilderland to review easement requests and report to the town board, which decides whether to grant the tax break. The first easement was granted for 57 acres off of Wormer Road where the Normanskill goes by a wild gorge.

Meanwhile, since municipal wells often provide safer water supplies than open reservoirs, Guilderland has applied for state funds towards a $6 million project that would bring two currently unused town wells back into use.

The filtration system is needed to treat a high concentration of manganese and iron in the wells that were historically a major source of water for residents; now the Watervliet Reservoir is the town’s major source of drinking water.

The town currently has agreements with Rotterdam and Albany to provide water back and forth in case of an emergency but, if the state grant, covering 60 percent of costs, were received, Guilderland would have water produced on its own town property.

Returning to our original point, in the here and now: The Watervliet Reservoir is currently Guilderland’s major source of drinking water. We need to protect it.

Guilderland resident Aaron Mair — who retired from the state’s health department to become the Adirondack Council’s wilderness campaign director — put it eloquently on Oct. 4.

He told the zoning board members, “The red line is death. The blue line is life …. We should be buying land around this reservoir. Our water is a critical asset to this community as well as the city of Watervliet. This is more than two lines. You are making a public health decision. You’re making an environmental decision ….”

So, buoyed by the widespread public support shown for protecting the reservoir, we urge the town of Guilderland and the city of Watervliet to purchase the land.

Even if Guilderland is able to secure the millions of dollars needed to use its wells again, the reservoir land — 10 acres for $80,000 — is a wise acquisition for the people of Guilderland and for the good of the environment.

Humans have forced climate change and we are in the midst of mass extinctions of species. Natural landscapes pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store carbon in trees, shrubs, grass, and soil.

If the town owned the land, the historic cemetery would be protected; the current residents who spoke of their love of the land would have it preserved; the many newcomers could gain an appreciation of once-rural Guilderland with its deer and bobcats, its eagles and egrets — and yes, our water source and Watervliet’s would be protected.

We would be taking one small step towards the preservation of our Earth.