The butterfly in the coal mine

The Sept. 20 public hearing on a proposed law to protect and preserve native trees did exactly what a public hearing should do — inform receptive lawmakers, in this case, the Guilderland Town Board, how to improve the legislation.

It also pointed up the need for the public to be informed.

One of the speakers, Laura Barry, a Master Gardener who worked on a committee that helped draft the bill, gave an eloquent statement on the need for the law.

“I believe this law is a big step in the right direction because we’re at a time in history when just shrugging our shoulders and doing nothing is unacceptable. All of us can do something to change the trajectory of impending climate catastrophe and trees are one of the things we can do,” she said, noting their ability to capture carbon dioxide to reduce climate change.

She spoke, too, of the need for planting native trees that sustain insects, birds, and animals.

“There is a big education gap,” said Barry. The hearing showed that to be true.

The law would set up a five-member Tree Preservation Committee to prepare and keep current a forestry plan for the town. Committee members would aid already existing town boards — planning, zoning and conservation — with on-site information as they review proposals.

The bill states the highway superintendent and parks director will see that trees in parks and rights-of-way are replanted in accordance with the forestry plan. Residents can plant or cut down whatever trees they want in their own yards but would have a list of native trees to consult if they so wished.

Several of the speakers owned tree-related businesses in town. Jim Gade, owner of garden center and nursery Gade Farm and president of the Albany County Farm Bureau, said he agreed with Barry on the importance of native plants. “We sell a lot of natives,” he said.

But he raised a legitimate question about one sentence in the proposed law: “No person shall remove, clear or cut all or substantially all of the trees, shrubs or brush on any area of land in the Town measuring 10,000 or more square feet except pursuant to and in conjunction with an approved subdivision plan, approved site plan, approved special use permit, building permit or part of a recognized agricultural practice.”

Gade said 10,000 square feet is not big and he has a greenhouse that size. He correctly pointed out there are many properties in rural Guilderland larger than that where a landowner might, for example, want to cut trees for firewood.

“We might need to further define ‘agricultural practice,’” responded Councilman Jacob Crawford, suggesting it might also be appropriate to look at a time frame for logging.

Supervisor Peter Barber, at the end of the hearing, when the board voted to continue it till Nov. 1, said that that part of the bill will be reworked.

David Orsini, who lives in Guilderland and owns a landscaping business in town, suggested the bill be viewed “from more of an educational standpoint because it seems like everybody hears ‘law’ and they worry they’re going to get in trouble.”

Orsini said that Guilderland residents should “have a proactive way to get answers without feeling like they’re going to get in trouble.”

“That’s correct,” Barber responded, adding that a lot of people don’t know about trees so the forestry plan, once created, would let residents know what are the better trees to plant for the soil conditions they have.

Two of the speakers illustrated the educational gap that the bill seeks to address. Both of them acted as if the town were trying to pull a fast one in drafting the bill, not informing the public.

“When was this tree committee like created …,” asked Kyle Trestick, who owns KT Tree Services and is currently belatedly applying for a controversial special use permit for tree waste. “I only got this this afternoon,” he said of the proposed law.

Barber explained that the tree committee has not been formed; its members would be appointed only after the law is adopted. He also said the public notice on the hearing was “sent out four or five different ways.”

The Enterprise wrote in March, six months ago, about the group that was helping to draft the bill. The town board discussed the proposed local law at its August meeting, which we also reported on, and the bill was posted to the town’s website.

Citizens in a democracy are responsible for their government and need to pay attention. The town board was wise to continue the public hearing to November so that more residents will have a chance to read and understand the bill and to be heard.

“The tree committee’s going to decide whether or not a tree is going to come down?” asked Trestick.

“No,” responded Barber. “They don’t decide that. They come up with a forestry management plan.” The plan is to provide guidance for the parks and highway departments as well as homeowners, he explained.

“You don’t go before any board to get permission to cut a tree down,” Barber stressed.

Developer Angelo Serafini voiced the strongest objections to the bill and also showed the greatest lack of understanding. Like Trestick, he said of the forestry plan proposal, “No one knew about it … The landowners, the Guilderland taxpayers didn’t know about it.”

Serafini also said, “I don’t know any house in town that hasn’t already cleared 10,000 square feet. Based on what I’m reading, they would automatically have to come to this new tree committee … hire an arborist,” which he said would cost at least $200 an hour.

“No, it doesn’t say that …,” responded Barber. “It’s not up to this tree committee to manage a person’s property … These are not punitive. There’s nothing in there that sanctions people,” he said of the bill.

“We’re not going to go back and tell every homeowner in Guilderland … ‘You need a permit for a house that was built 20 years ago,’” said Councilwoman Christine Napierski.

To cap his presentation, Serafini handed the board members pictures of the pine bush preserve. “Their policy is to clear-cut everything,” he said, asserting that the pine bush preserve would be “completely exempt from this law but we are not.”

He asked, “So why is it fair that Guilderland taxpayers who are paying taxes on the property have to abide by a tree-cutting law and the largest entity in the town of Guilderland who owns all the property cuts everything they want when they want?”

He went on about the pine bush preserve, “It’s not fair to cut down everything under the guise of management and, if it’s not cut down, they burn it down. I own land next door and I can’t do that …. It’s not fair to us. We’re Guilderland taxpayers. They’re not.”

The Albany Pine Bush Preserve was created by the state legislature in 1988 because it is a rare inland pine barrens. The preserve has been designated as a National Natural Landmark and now totals 3,400 acres spread over several municipalities. This pales in comparison to the 50,000 acres of original pine barrens.

This remaining sliver of an ecosystem has been carefully maintained so that the species it supports don’t become extinct. There is no “guise of management” in removing invasive trees or in prescribed burns; rather, science is followed.

While many think of fire as a solely destructive force, Neil Gifford, conservation director for the preserve, explained to us how fire recycles nutrients in a way that benefits plants. “Fire is taking nitrogen in particular, but also phosphorus, calcium, potassium, and other nutrients and releasing them into the soil and making them available for plant uptake,” he said.

Plants and animals in the pine bush depend on fire to complete their life cycles. He gave an example of the heat of a fire opening pine cones to release the seeds while simultaneously the fire prepares an appropriate seed bed, removing competing vegetation, and fertilizing the soil.

Also, because the trees are thinned, the remaining trees are healthier and better able to withstand threats such as those posed by invasive species.

Human beings need to learn, even belatedly, that other species matter.

Yes, it is true that private landowners and businesses in town pay local taxes while state lands do not. Developers are regularly adding homes and businesses to Guilderland, and the local property taxes pay for the services they require.

Local taxes pay for water systems and sewer systems, for police and ambulance services and, most expensive of all, for schools. The pine bush preserve uses little, if any, of these services. It houses no elderly residents who need senior services or ambulance rides, and no children who need schooling. One might argue that it is developers who are causing local taxes to rise.

What the pine bush preserve does offer is a chance for people to rejuvenate and learn from a fast-disappearing natural world. Both its trails and its educational center are well used.

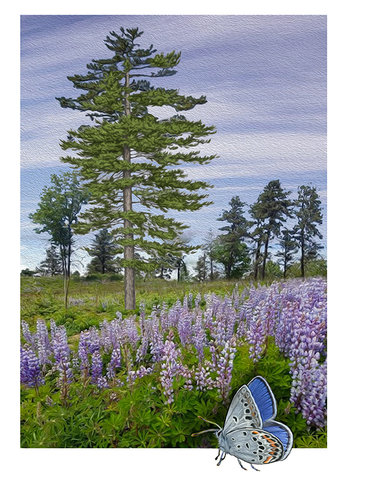

We have urged on this page before that Guilderland adopt the Karner blue butterfly as its totem. This would make citizens proud and aware of our role in the natural world.

Gifford sees the Karner blue butterfly as the canary in the coal mine — its demise warning of a grave danger. When the pine barrens ecosystem was healthy, it was able to support tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of the butterflies. “Ecosystem health declined to the point where it was only able to support a couple hundred,” said Gifford of a low point in the 1990s.

By managing the preserve and improving the habitat, the preserve now has 10,000 to 15,000 Karner blue butterflies, said Gifford. He is a member of the US. Fish and Wildlife Service federal recovery team that drafted a plan for the Karner blue, with the hope of getting the butterfly off the endangered list.

This is a powerful symbol of hope — of how humans can right past wrongs — but the butterfly is also an emblem of the necessity of balance.

As part of his job, Gifford reviews development plans and works with municipal planning agencies and the applicants to try to minimize impacts on the pine bush. The goal is to strike a balance between economic development and conservation, he said.

Gifford correctly notes, “It is ultimately the natural world that protects us and provides our ability to live on the planet …You can’t just have economic growth. You also have to have conservation … In a human-dominated world, increasingly, it’s our responsibility to do that work ….

“The beauty of the Albany Pine Bush and the work we’re doing is to show that it’s successful even for a globally imperiled ecological community and a whole bunch of rare species,” said Gifford. “If we can do this here in Albany, using prescribed fire … in an urban landscape to manage a globally-rare ecosystem and show that it’s working … you can do it pretty much anywhere.”

Guilderland’s proposal to preserve and promote the planting of native trees is another way to strike that balance — and to serve as an inspiration for other towns. We urge the Guilderland Town Board to persevere for the good of our future.