Mohicans, forced from their ancestral lands, still connect to their heritage here

ALBANY COUNTY — In 1854, John Wannuacon Quinney was invited to make a Fourth of July address in Reidsville, between Clarksville and South Berne. His tribe, the Mohicans, had fought with the patriots in the American revolution, helping to defeat England.

Quinney noted that he was standing on what should have been the property of his tribe and asked, “Where are the 25,000 in number and the 4,000 warriors who constituted the power and population of the great Muh-he-con-ne-ok Nation in 1604?”

He noted the two-and-a-half-century decline of his tribe and said, “Nothing that deserved the name of ‘purchase’ was ever made … Let it not surprise you, my friends, when I say that the spot on which we stand has never been purchased or rightly obtained, and that by justice, human and divine, it is the property now of the remnant of that great people from whom I am descended.

“They left it in the tortures of starvation and to improve their miserable existence … For myself and my tribe I ask for justice. I believe it will sooner or later occur. And may the Great and Good Spirit enable me to die in hope.”

The Mohican diplomat died the next year.

But his words were read last Thursday by his descendent, Bonney Hartley, to a crowd that packed the Bethlehem Historical Association’s Cedar Hill Schoolhouse Museum.

Hartley, the tribal historic preservation officer of the Stockbridge Munsee Community, went over the history of her people, which had settled on the Mahicannituck river, named the Hudson River by Europeans. They called themselves the People of the Waters That Are Never Still, the Muh-he-con-ne-ok, today called Mohicans.

As with many American tribes, the Mohicans’ traditional ways of life were disrupted by European settlers, and the tribe was forced to move from its homeland, assigned to a distant reservation. Today, there are about 1,500 Mohicans, with roughly half of them living on a reservation in northeastern Wisconsin.

The link between the modern inhabitants of the town of Bethlehem and the descendents of its ancient people was made through physical objects. Mohican artifacts were unearthed in the 1980s by Floyd Brewer and a band of enthusiastic volunteers who called themselves the Bethlehem Archaeology Group.

The group found evidence of what it termed River Indians from 1600 B.C., unearthing dozens of unusually shaped projectile points typical of the group as well as tools used to grind acorns and other seeds into food.

“They did a great deal of work at several different sites,” said Susan Gutman who has helped assemble display cases at the schoolhouse to document Mohican history.

She declined to name the sites because, she said, “The tribe has purchased some of their tribal lands in Bethlehem where human remains were found; it’s special to them.” She explained further, “Having people there with metal detectors would be disrespectful.”

The exhibit asks, “Why is there a Mohican on the Bethlehem Town Seal?”

The seal depicts Henry Hudson, in 1609, standing on one side of his ship, the Halve Maen, or Half Moon, and a Mohican, with a cornstalk and beaver, on the other side. Gutman said it is commonly believed in Bethlehem that Hudson actually set foot in town where Henry Hudson Park is now.

“We tried to subtly point out that’s not accurate. We’re close,” she said.

The Bethlehem town seal shows Henry Hudson and a Mohican on the banks of the river named for the explorer. The People Of The Waters That Are Never Still called the river Mahicannituck.

Based on the work of Shirley W. Dunn, the historian that the tribe subscribes to, author of “The Mohican World, 1680-1750,” Hudson actually landed on the other side of the river at what is now Castleton.

Gutman and her husband, Carl, who are not Native Americans, have been involved in Native American culture since they were first married, 50 years ago, and served as VISTA (Volunteers In Service To America) volunteers on an Apache reservation. The couple is traveling this week to St. Louis to visit ancient Indian burial mounds.

The artifacts unearthed by Brewer were inventoried by Susan Leath, Bethlehem’s historian, as the town building where they had been stored underwent renovation. Leath, who did graduate work in anthropology at Brown University, first tried to interest the New York State Museum in the collection Brewer’s group had amassed, primarily at Goes Farm. The artifacts dated back to 6000 B.C., she said.

“The museum turned us down,” said Leath. “But one of their archeologists came out to look and saw bone material that was human remains.

“What!” she said, echoing the surprise she had felt at the time. “So we reached out to the Mohicans,” she went on.

Artifacts, including pottery shards, stone tools, animals and fish bones from meals — it all fit in the back of a van — were donated to the Mohicans and are now kept in curatorial space at Hartley’s Troy office.

Last summer, in late August, a reburial ceremony was held by the Mohicans. At a feast afterward, Leath talked with a tribal elder who had come from Wisconsin for the ceremony, Jeremy Mohawk. “He talked to me about the spirituality of remains, and told stories of the bear and the turtle,” said Leath.

The day after the ceremony and feast, Leath was driving, early in the morning, to visit her mother in the hospital. “It was a really tough time for me, personally, just trying to get through that one day,” she recalled. “And there was a black bear, walking across the street, in front of me,” she said, with wonder in her voice.

“It gives me chills even now, to think of it … It made me feel touched by the creator.”

Leath concluded, “My mom ended up passing away in October … He’s my special bear.”

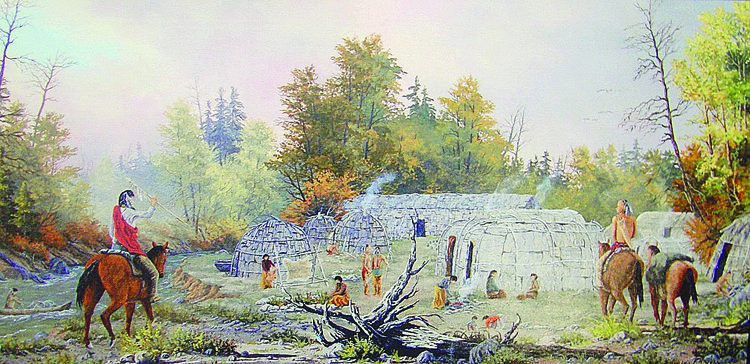

A painting in the Arvid E. Miller Library at the Mohican Nation reservation in Wisconsin depicts the homes Mohicans once had on the shores of the Hudson River. Miller, a tribal council president, led his people for 26 years and helped found the National Congress of American Indians.

Leath feels that Bethlehem’s ancient artifacts are now where they belong.

“It felt really good to give them to the Mohicans,” she said, explaining that their value went beyond the scientific purposes a museum would have used them for. “It’s more spiritual,” she said, adding, “It did become very personal.”

Hartley has loaned back some of those artifacts for the current exhibit, and objects found on other Bethlehem farms have been included, too.

The schoolhouse, at 1019 River Road, is open every Sunday from 2 to 4 p.m. through the end of October and the public is welcome to view the exhibit, free of charge.

The display cases are topped with a painting by David Cunningham Lithgow, an Albany muralist from Scotland who worked in the late 19th Century and in the first half of the 20th Century. His painting depicts Mohicans on the shore of the Hudson River.

“It’s huge and very beautiful. It’s our prize possession,” said Gutman.

Gutman said one of her favorite pieces on display is a grinding stone and hand stone. “It’s amazing both pieces were found together,” she said.

She went on, “The knowledge that there was an Indian presence here thousands of years ago and that we’re walking in their footsteps, is enchanting … They had a good life here, hunting and fishing in a chain of villages … We just don’t think about it: Before anyone was here, this was all Indian.

“They had their own Trail of Tears,” she said, referencing the Cherokees’ relocation, forced by the federal government, from lands east of the Mississippi to Oklahoma. “It decimated their numbers.”

Gutman went on, “North American Native Americans had no concept of owning land. That’s why they were cheated again and again.”

Gutman went to a conference in May in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where a missionary in the 1700s had set up a village for Mohicans. “The tribe held the conference. They said prayers in their language … They had a rough time but they’re a proud and humble people. They’re very tenacious in holding on to their history and yet they are not at all vindictive.”

Referencing James Fenimore Cooper’s most popular Leatherstocking Tale, “The Last of the Mohicans,” set in 1757, in the midst of the French and Indian War, Gutman said, “That’s not accurate … They’re still very much here.”

Bonney Hartley, who has a master’s degree in social science - international relations, answers questions after her talk last Thursday. She is the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Stockbridge Munsee Community and a direct descendent of John Quinney.

History of the Mohican Nation

The Mohicans, who were sometimes called River Indians, built wik-wams, circular homes made of bent saplings covered with hides or bark; they also built longhouses where several families of the same clan could live together, according to a history written by the Stockbridge-Munsee Historical committee, which Hartley shared. The women largely saw to the home, the children, and the gardens while the men went further afield to fish, hunt, or serve as warriors.

The Mohican lands went from what is now Lake Champlain south to Manhattan and on both sides of the Mahicannituck, now called the Hudson River, west to Schoharie Creek and east into Massachusetts, Vermont, and Connecticut.

The coming of Europeans drastically changed the tribe’s way of life.

Henry Hudson, in his second attempt to find a northeast passage to China, sailed up the river that now bears his name. Hudson’s exploration in the early 1600s laid the foundation for Dutch colonization of the area.

As the fur trade grew, and the coveted beaver and otter were harder to find, tensions grew between the Mohicans and the Mohawks, Haudenosaunee people to the west. The Mohicans were eventually driven east near the Housatonic River in what would become Connecticut and Massachusetts.

The Mohicans stopped making traditional clothes, baskets, and pottery, using European goods instead. The vast lands the Mohicans had used for gardens and fishing and hunting began to have boundary lines and fences as the lands were declared to belong to European monarchs by the Doctrine of Discovery. The doctrine originated in 15th-Century papal edicts and was later part of royal charters and court rulings, justifying the discovery and domination by European Christians of lands inhabited by indigenous peoples.

The diseases the Europeans brought with them also had devastating consequences, sometimes wiping out entire Native villages.

A Christian missionary, John Sergeant, started a mission in the 1730s in a place that came to be called Stockbridge on the Housatonic River. The Mohicans’ native language and customs began to disappear as they adopted Christian ways. The Mohicans who lived there were called Stockbridge Indians.

When the surviving Mohican warriors returned home from fighting in the Revolutionary War, according to the historical committee’s telling, they discovered plans had been made to move them from Stockbridge, their Christian village.

“It became apparent after the Revolutionary War, with their numbers greatly reduced and intruders (called ‘settlers’) using unscrupulous means to gain title to the land, that the Stockbridge Mohican people were not welcome in their own Christian village any longer,” wrote the historical committee, chaired by Dorothy W. Davids.

The Oneida, who had also fought for the colonists in the war, offered the Mohicans part of their farmland and forests, so the Stockbridge Mohicans moved near Oneida Lake in the mid-1780s.

But then pressure from land developers forced the Native Americans out of New York State. A treaty was negotiated in 1822 and, over the years, the Stockbridge Mohicans traveled to Fox River in what became Wisconsin.

“But adopting the white man’s religion and education did not assure acceptance,” the historical committee wrote. “As long as Native people held land, they were subject to removal.” As soon as the Fox River was perceived to be a major waterway, the Stockbridge Indians were moved to the east shore of Lake Winnebago in 1834.

Two years before, in 1832, Congress had enacted the Indian Removal Act, forcing all Native Americans to lands west of the Mississippi.

“A group of Stockbridge Mohicans, fearing the inevitable, moved to Indian territory in 1829,” the historical committee wrote. “Many died while making this journey. Some reached Kansas and Oklahoma and married into other tribes … A group of Munsee joined the people at Stockbridge, Wisconsin, and were accepted into the community.” They came to be called Stockbridge-Munsee.

By the late 1800s, most every Native nation in the United States was assigned to reservations. “Poverty prevailed for most people,” the historical committee wrote. “Treasured wampum belts and other cultural artifacts, craft materials, and even traditional clothing were sold to collectors for a pittance.”

Congress passed the General Allotment Act in 1887, dividing up reservations to allot portions to individuals, which, the historical committee wrote, was “a very successful way of removing land from tribes by making it possible to deal with individuals who had little experience with private ownership.”

The 1887 act allowed lumber companies to cut down the trees on the Stockbridge reservation, leaving the land with little economic value. Hard times grew worse during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act, known as the Indian New Deal, was meant to reverse the federal government’s policy of assimilation, and helped tribes get federal funds to reorganize their own governments and retrieve some of their lost lands.

Mohicans today

Hartley gave an upbeat account of life on the Mohican Nation reservation today. A casino there, she said, provides an economic base that made a “big difference.” The casino is the largest employer in Shawano County with about 600 employees; over half are not Mohicans.

“Everybody in my mom’s time was forced to leave after high school,” Hartley said. “Now it’s possible to stay in the community.”

The land that had been stripped by logging companies has been reforested. “Now it’s really beautiful,” said Hartley.

She projected pictures, showing a new elder center and health clinic. Tribal goals, she said, include self-sufficiency and historic preservation.

Hartley works out of Troy in an extension office established in 2015, which is closer to archaeological sites and burial grounds.

In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was enacted, requiring federal agencies as well as organizations that receive federal funds to return “cultural items” — which can range from sacred objects to human remains — to lineal tribal descendants.

This past week, Hartley participated in a reburial at Ellis Island, which was an ancient Mohican site. She called the reburial “really meaningful.”

“Our cultural sites are here,” Hartley told the Bethlehem crowd.

“We don’t normally take positions for or against,” Hartley said of proposed projects. But in the case of the Pilgrim Pipeline, a proposed 178-mile pipeline that would carry oil from Albany to coastal New Jersey, a tribal resolution opposed it, she said.

Many in the Mohican tribe have taken “Homeland Trips,” traveling from Wisconsin to New York State to visit, for example, the New York State Museum, which displays some Mohican artifacts.

The museum’s predominant display is about the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, but, Hartley said, “They have a display case with baskets and a wooden ladle” made by Mohicans. “There’s an incredible behind-the-scenes collection of baskets, moccasins, things that don’t fall under NAGPRA,” she said, referencing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

Looking to the future, Hartley said, “I would like to see us do more public education. Now we’re in emergency mode, putting out fires … People out here desire more of a sense of place.”