State health commissioner declares EEE an ‘imminent threat’

This week, the state’s health commissioner, James McDonald, issued a “declaration of an imminent threat to public health” for eastern equine encephalitis after a resident of Ulster County died of the disease.

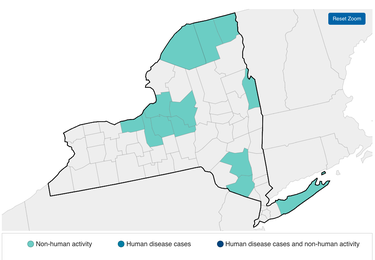

“Eastern equine encephalitis is different this year,” McDonald said in a statement. “While we normally see these mosquitoes in two to three counties each year, this year they have been in 15 counties so far, and scattered all over New York State.”

He noted there is no human vaccine for the virus. There is a vaccine for horses, which, in August, the agricultural commissioner Richard Ball, urged horse owners to get.

While the virus is rare, there is no cure. The disease is fatal for humans about 30 percent of the time and fatal for horses about 90 percent of the time.

People cannot catch EEE from horses or other animals nor can horses spread it among themselves. It is spread only through the bite of a mosquito.

Only female mosquitoes have the needle-shaped proboscis needed to puncture skin and draw blood, which is necessary for producing eggs. Male mosquitos subsist on nectar.

Out of 112 mosquito genera, just three transmit human diseases. Aedes mosquitoes carry yellow fever, dengue, and encephalitis. Anopheles mosquitoes carry malaria and harbor filariasis and encephalitis. Culex mosquitoes carry encephalitis, filariasis, and the West Nile virus.

Eastern equine encephalitis circulates in a bird-mosquito transmission cycle while infections of most mammals are considered “dead end hosts,” according to a study published in Current Biology, “Dynamics of Eastern equine encephalitis virus during the 2019 outbreak in the Northeast United States” in July 2023.

The paper goes on to note that the virus has caused periodic outbreaks in humans and horses in the United States since its discovery in 1933 but human cases are typically rare with about seven annually in the United States.

The largest human outbreak in more than 50 years, the study says, was the 38 cases reported in 2019, including 12 deaths.

“Mosquitoes, once a nuisance, are now a threat,” McDonald’s statement went on. “I urge all New Yorkers to prevent mosquito bites by using insect repellents, wearing long-sleeved clothing and removing free-standing water near their homes. Fall is officially here, but mosquitoes will be around until we see multiple nights of below freezing temperatures.”

McDonald’s declaration unlocks state resources to help support EEE prevention response and activities by local health departments — including ongoing mosquito spraying efforts — from Sept. 23 to Nov. 30, according to a Monday release from the governor’s office.

The fatal case in Ulster County — the first human case in New York since 2015 — was confirmed on Sept. 20 by the state health department’s Wadsworth Center, the governor’s office said. No details about the individual were released.

Immediately after the case of EEE was confirmed, the release said, the governor activated state agencies including the departments of health, environmental conservation, and parks, “in a robust, coordinated response to expand access to insect repellent at State parks and campgrounds, increase public outreach and urge New Yorkers to follow recommendations to reduce risk of mosquito-borne illness.”

The state parks office is making mosquito repellent available to park visitors at park offices, visitor centers, and campground offices and is placing signs to raise awareness.

The DEC is also posting signs at campgrounds, popular Hudson Valley trailheads, environmental education centers, and other state lands to raise awareness about EEE.

A social-media campaign is being launched to raise awareness of EEE and other mosquito-transferred pathogens and steps to avoid mosquito bites, including using repellent, covering exposed areas of skin, and avoiding outdoor activity at dawn and dusk.

Other states, including Massachusetts, Vermont, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and New Hampshire, have also reported human EEE cases this year, the governor’s office says, and 18 cases of EEE have been identified in horses across 12 counties in New York State this year.

CDC

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with data current through Sept. 24, report just ten cases of EEE in humans in 2024: one each in Vermont, New Jersey, Rhode Island and Wisconsin, two cases in New Hampshire, and four in Massachusetts. Apparently, the CDC had not yet accounted for the fatal case of EEE in New York’s Ulster County.

The 10 reported cases are up from just three cases reported by the CDC in late August.

On average in the United States, 11 human cases of EEE are reported annually, the CDC says.

“Eastern equine encephalitis virus transmission is most common in and around freshwater hardwood swamps in the Atlantic and Gulf Coast states and the Great Lakes region,” says the CDC. “All residents of and visitors to areas where eastern equine encephalitis virus activity has been identified are at risk of infection.”

People over 50 and under 15 years old are most at risk for developing severe disease, the CDC says, and overall only 4 to 5 percent of human EEE virus infections result in eastern equine encephalitis.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus infection is thought to provide life-long immunity against reinfection, the CDC says, but the immunity does not protect against other alphaviruses such as western equine encephalitis virus, flaviviruses such as West Nile virus, or bunyaviruses such as La Crosse virus.

EEE virus can cause a febrile illness, which lasts a week or two, and causes fever, chills, body aches, and joint pain. Most people recover completely when there is no central nervous system involvement, the CDC says.

However, the virus can also cause neurologic disease, which can include meningitis, an inflammation of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord, or encephalitis, which is a swelling of the brain, the CDC says. Signs and symptoms include fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, behavioral changes, drowsiness, and coma.

For horses, according to the state’s agriculture department, typical symptoms of EEE virus include staggering, circling, depression, loss of appetite and sometimes fever and blindness.