Sticky floors and glass ceilings must not determine a woman’s fate

The pandemic has laid bare inequities in our society.

One of them is gender inequality.

We’re pleased that our governor, Kathy Hochul, has acknowledged this and last week directed the state’s labor department to analyze the impact of the pandemic on women in the workplace and, importantly, explore equitable solutions.

Similarly, our former governor, Andrew Cuomo, recognized the racial inequities laid bare by the pandemic coupled with the racial reckoning brought on by the murder of George Floyd and required municipalities across the state to come up with reform plans for their police departments.

We have felt the effects of this locally. So, too, we all know women close to home — and indeed in our homes — who had to make difficult choices during the pandemic as schools and day-care centers were closed.

One of the speakers on Women’s Equality Day at a University at Albany event where Hochul announced the initiative was Starletta Smith. She directs the YWCA of the Greater Capital Region, helping homeless women and children who suffered more intensely than many of us during the pandemic.

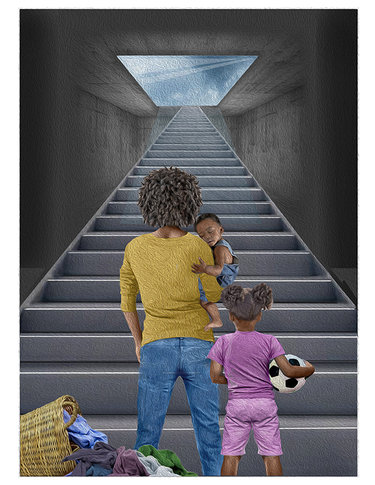

Smith spoke with passion about the hardship women endured during the pandemic when many had to choose between being employed and caring for their children; they had to decide whether to pay the rent or put food on the table. She noted, too, that needed mental-health services were shut down and domestic violence increased.

Smith concluded with a challenge for New York State: “Join us on our mission to break these cycles of oppression on women because we understand the system that divides, impoverishes, and destroys us cannot stand if we do.”

This is a mission that people of any gender and of all races should embrace. We are stronger if we are united. A society’s economic success is not a zero-sum game. More people working and being fairly paid enriches us all.

The state’s labor commissioner, Roberta Reardon, who will oversee the study, said, “When women are not part of our workforce, we are literally leaving money on the table. It damages our economy and it bruises our culture.”

Reardon also described her own experience of metaphorically opening a door and not seeing another woman — someone like herself — in the room and then either walking away from a great opportunity or feeling “like I had to armor up to be able to go into that room or I was not seen.”

She concluded, “That should never happen again … it’s just not right.”

Reardon said that taking “a closer look to see what the real story is” will lead to implementing “real solutions right now.”

Reardon’s reflection on not seeing others like herself — other women — when she opened the door made me remember being part of an experiment in the early 1970s when I was a student at Wellesley College. I sat with young women like myself — a counterpart to the Ivy League that still largely didn’t admit females — in a darkened lecture hall and was asked to react to projected pictures, to come up with a story, about, among other things, a woman in a white coat.

What we women largely saw was a technician and not a doctor. Men looking at the same picture of a man in a white coat saw a doctor.

This was an era, a half-century ago, when only 1 percent of federal judges were women, only 1 percent of engineers, 3 percent of lawyers, 7 percent of doctors, and 9 percent of scientists were women.

The lecture-hall pictures were part of research being done by Matina Horner who wondered why so few American women — with the number of educated women at an all-time high — pursued traditionally male professions. She concluded that American women feared success.

Being among the highly educated women who didn’t see a doctor in the picture, I believe it was a lack of expectation. We didn’t see ourselves as doctors, or lawyers, or editors, so we didn’t become them.

You need a vision, a clear vision, to form an expectation that may one day become a reality.

Yes, progress had been made. Every speaker and most of the leaders introduced at the UAlbany event, from the governor on down, were women. But, as Reardon said, “So much more needs to be done … The pandemic has taught us how fragile some of these accomplishments are.”

During the pandemic, she noted, as schools and daycare shut down, “women had to juggle full-time childcare while working — or they left the workforce altogether because they had to take care of their families.”

Reardon quoted a study saying that 39 percent of American women with children younger than 5 reported they had quit their jobs or had reduced their hours since the pandemic, and most mothers who cut back on their work did so even though they didn’t have adequate income.

“They did not have a choice,” she said.

In 2018, Hochul and Reardon co-chaired a study on closing the gender wage gap in New York State. In it, they correctly noted, “Any gender pay gap, no matter how small, is an injustice impacting not only working women and their families today, but also generations of women that will enter the workforce in the future.”

The 2018 report stated that New York had the narrowest wage gap in the nation with women earning the equivalent of 89 cents to each man’s dollar. Nationally, women earn just 80 percent of what men earn overall.

Narrowing the gap is moving in the right direction — but there should be no gap.

Though the gender pay gap is larger among women of color and grows as women earn more or seek higher education, the report says, it is not confined to any socioeconomic stratum or geographic region.

A map in the 2018 report, illustrating female earnings as a percentage of male earnings by county, shows Albany County as one of just a handful in the 86- to 90-percent range. New York City alone is 91- percent or above.

About a quarter of New York State workers belong to unions, the report says, which reduces the gender pay gap — a difference of 6 percent for union members compared to 22 percent for non-members. But only about 10 percent of apprentices in the state are women, and, as the report notes, apprenticeships are a key feeder system for unions.

Hochul and Reardon wrote that the causes of the wage gap are rooted in longstanding societal norms that will require multifaceted intervention.

These are the very norms that caused women, far more than men, to give up their work to care for their families during the pandemic.

“This intervention must take place across the socioeconomic spectrum — for women in low-paying and entry-level jobs (often referred to as the sticky floor), as they climb the career ladder and as they encounter the glass ceiling,” Reardon and Hochul wrote in 2018.

At last week’s event, Reardon congratulated Hochul on shattering that glass ceiling but said she looked forward to a day when it won’t be a rarity.

We believe some initiatives already underway — such as increasing aid for day care, both for parents and providers — can help close the gap. And legislation can make an important difference, too.

Federal legislation in 1972, known as Title IX, barred gender discrimination in federally funded education programs and activities, which has caused the number of girls playing high school sports to grow from fewer than 300,000 in 1971 to well over 3 million today.

A higher minimum wage helps women who are disproportionately in minimum-wage jobs.

Paid family leave would encourage men, not just women, to become engaged in child care from the start, perhaps instigating a life-long pattern.

The 2018 report includes a graph that depicts the median earnings of men and women, with and without children. Women with children make 3 percent less than women without children ($744 weekly compared to $765), which is known as the “mommy penalty” while men with children earn 15 percent more than men without children ($962 weekly compared to $842), known as the “daddy bonus.”

We don’t know if there were parallel experiments to Matina Horner’s a half-century ago to see if men could envision themselves as nurturers — caring for babies or for elderly or ailing family members. We presume not because that role has traditionally been undervalued.

But, for our society to prosper, the role of nurturer must be valued and must not be gender specific.

“Knowledge is power,” said Reardon at last week’s Women’s Equality Day event. “Once we know the full scope of what we have to deal with, we can take those important steps to implement real solutions right now.”

We’ll be watching to see what the new report uncovers, with testimonies gathered from across the state, and we’ll advocate for fair solutions that will make a difference and close the gap.

At The Enterprise, we’ll continue in our podcasts to interview and on our pages to write about and picture women in a wide variety of roles in hopes that others will see themselves in those roles — no armor needed. We see you.

In the meantime, each of us can take up the challenge thrown down by Scarletta Smith: Work together to break the cycle of oppression on women.