Profiles in tide turning

“There’s so much we don’t know,” said Laura Barry.

She was talking, in this week’s Enterprise podcast, about human beings who have a lot to learn about the natural world.

Lacking in knowledge, we humans have obliterated other species through our selfishness or perhaps just our carelessness.

One thing I do know with absolute clarity is that individual people, like Laura Barry, can make a difference.

Several decades ago, when I was writing about the 150th anniversary of the Helderberg Anti-Rent Wars, I spoke with Pete Seeger about a song he had popularized from that rebellion.

“One of the extraordinary parts of America, which usually is skipped or skimmed over in American history courses,” Seeger told me, “is the way American history has been formed, not always by the presidents and the officials, but by the rank and file people who kept pushing.”

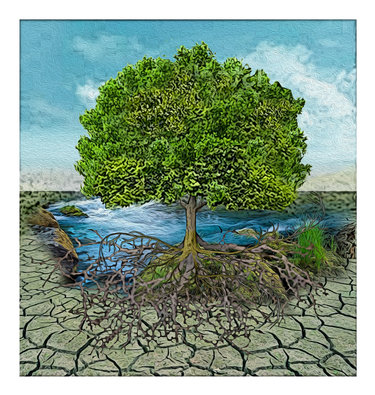

That is happening now with the green movement. You can see it on the pages of our newspaper. Local individuals are finding ways to, bit by bit, work to save our planet.

Barry said she hit a low point last summer, thinking, “Man, with the climate change and people’s attitudes, this isn’t good …We’re not going to make it with the warming of the planet … Time is running out.”

But then she read a piece by a scientist “who turned it around and she said, ‘Oh, time isn’t up. If we could just plant more trees because the trees sequester the carbon and it will buy us time.’”

Barry, a retired teacher, had served on Guilderland’s environmental conservation committee where she’d walked properties slated for development and cataloged the plants on land across the town.

She lives in the historic McKownville neighborhood where century-old trees form a luscious green canopy over the roads. But, as she and others walked her neighborhood’s streets to count the trees, they discovered over 100 street trees had died but not been replaced.

“I could see there is no plan for replacement. There’s no plan for care,” said Barry. “We’ve been kind of on borrowed time throughout the town.”

So she became part of a group, working with the town’s planner, supervisor, park director, and others, to come up with a bill that would create a forestry committee to develop a forestry plan for Guilderland. We advocated for that in this space last week.

Just as Ellen Howie made a difference by speaking out for No Mow May, supporting pollinators in her Altamont yard, so too Laura Barry, a single citizen, is making a difference. Read her front-page profile to see if it inspires you to plant even a single native plant in your own yard each year.

Meanwhile, we have another story this week, about a New Scotland resident, Paul Steinkamp, who is advocating for a “green road.” Steinkamp and his wife, Mardell, for nearly half a century have owned 40 acres on Picard Road where they have a plant nursery.

Picard Road runs along the base of the Helderberg escarpment and much of the land along the road is protected from development by conservation easements, part of a 3,700-acre corridor, stretching from the Black Creek Marsh to John Boyd Thacher State Park. We’ve advocated in this space over decades, parcel by parcel, to preserve that all-important corridor.

Steinkamp for a year has been trying simply to get signs posted, he told our reporter Sean Mulkerrin, to notify motorists that they share the road with others — cyclists, walkers, and high school runners.

Every spring, the road is peppered with handmade signs, letting motorists know that amphibians — the area is one of the richest in the state for herptiles — are crossing the road to get to vernal pools to mate.

Just as Barry noted that cities like Albany are ahead of suburbia in having forestry plans, Steinkamp has also looked to cities and cites Albany’s 2021 bike plan that recommends special lanes for cyclists.

“Wouldn’t it be good to have a rural one?” Steinkamp asked of a designated bike lane on Picard Road.

He looked to Tucson’s street-design guide, which recommends, when different types of dedicated bike lanes are to be installed, that, for safety reasons, certain areas of pavement be entirely painted green or that the lane receive green “conflict markings.”

“And I thought, ‘Wasn’t that something? They told me it couldn’t be done.’ Well, it can be done. Anything can be done and anything can be tried,” Steinkamp said.

On Monday, county workers installed signs on Picard Road — anything can be done if, as Pete Seeger said, people keep on pushing.

Last week, we got a letter from Enterprise reader Mary Jo Batters with an idea that would take green commitment all the way to the grave.

She cited our August editorial, “Can Guilderland help save the planet? Maybe if we plan it,” which mentioned changing trends in funeral customs. “In addition to embalming and cremation,” Batters wrote, “there is a third option called natural burial or green burial.

“The body is neither embalmed nor cremated, but is placed in a biodegradable casket that is placed in a grave with no vault.”

We checked and two local cemeteries — Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery in Niskayuna and Calvary Cemetery in Glenmont — offer natural burials.

American funerals are responsible each year for the felling of 30 million board feet of casket wood, 90,000 tons of steel, 1.6 million tons of concrete for burial vaults, and 800,000 gallons of embalming fluid, according to the Order of the Good Death green burial website.

While scattering ashes does not create the problem of water use and fertilizers used in cemeteries, cremation facilities create mercury and carbon dioxide in large quantities.

The popularity of green burials, and of home burials, both of which are legal in New York State, are growing in popularity, according to The New York Times.

We loved the way Mary Jo Batters ended her letter, with these lines from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”:

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

We’d like to end where we began, with Laura Barry’s thought that there is much we do not know.

Barry cares about the birds. She notes that bird populations have decreased by half, and one of the reasons she’s so strongly committed to native plants is that invasive trees don’t have the caterpillars the birds need; one clutch of chickadees needs 6,000 to 8,000 caterpillars when they are growing in the nest, Barry says.

Right now, song birds are migrating. We’re pleased New York State has a Lights Out initiative, directing state-owned and managed buildings to turn off non-essential outdoor lighting from 11 p.m. to dawn during the spring migration and now during the peak fall migration, which runs from Aug. 15 through Nov. 15.

Migrating birds rely on constellations to navigate, which can be disrupted by outdoor lights. Fatal light attraction, when migrating birds become disoriented, kills between 500 million and a billion birds each year in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In 2011, we praised the town of Knox on this page for promoting dark skies by requiring new outdoor light installations to have shields so the lights would only shine down, not up into the night skies. When it came to clarifying the law for enforcement though, a later board had the attitude espoused by its supervisor: “People came up here because they want to be left alone.”

None of us are alone, regardless of where we choose to live. We, as humans, are part of a larger web of life.

Birds use the stars, as well as the earth’s magnetic fields, to migrate every year. Is that something you knew?

Here’s something I didn’t know until, just now, I was looking into how a Cornell researcher had used a planetarium — and switched the projected stars — to see what specifically the birds used to navigate: Dung beetles, too, depend on the stars, particularly the Milky Way.

“Starlight from tens of thousands of light-years away, still has enough power to excite the nervous system in the limited eyes of the lowly dung beetle, helping it know where to go,” wrote Brian Resnick, describing another planetarium experiment where little hats were fashioned for dung beetles so they couldn’t see the stars.

Our goal, as a newspaper, is to educate and empower citizens. Maybe, like Guilderland, other towns will be inspired to draft bills to protect their trees or, as Knox did more than a decade ago, help keep skies dark so stars can be seen.

Human hubris need not be our nemesis. It’s not too late if enough individuals — like Ellen Howie, Paul Steinkamp, Mary Jo Batters, Marsha Carlson, Joan McKeon, and Laura Barry — keep on pushing.