Do state-set low-cost internet services slow rural broadband expansion?

HILLTOWNS — What is keeping rural areas from having internet service? Does lack of infrastructure or finances play the biggest role?

The state is currently appealing a preliminary injunction set by a federal court that determined New York’s Affordable Broadband Act may not achieve its desired effect to bridge the digital divide but instead reduce internet access.

The act, which was bundled with New York’s budget bill last year, required that internet service providers offer a plan costing just $15 per month with a minimum download speed of 25 megabits per second for anyone who receives or is eligible to receive public services like reduced-price lunches, Medicaid, supplemental nutrition assistance program benefits, and so on.

A complaint was filed on April 30, 2021 by the New York State Telecommunications Association and the other trade associations against the state’s attorney general, Letitia A. James, in the United States District Court Eastern district of New York.

Citing statements from various companies, Justice Denis Reagan Hurley, who was appointed by former President George H.W. Bush, stated in his decision that “the evidence before the Court suggests the ABA may not achieve its desired effect – and in fact reduce Internet access statewide.”

The companies Hurley referred to, which include Catskills Communications Inc. and Delhi Telephone Company, said that the law would force them to abandon projects. Empire Telephone Corporation said that it wouldn’t want to surpass the exemption threshold of 20,000 internet customers by continuing a project that would expand service into the city of Binghamton.

“Given the foregoing, a balance of the equities and the public interest support a preliminary injunction keeping the status quo,” Hurley wrote.

No date has been set yet for the appeal arguments, Catherine O’Hagan Wolfe, the clerk with the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, told The Enterprise this week.

Background

The Affordable Broadband Act is in line with New York’s mission to close the digital divide, which itself is part of a national effort to ensure that internet access — something once seen as a luxury that has quickly become a necessity — is available to all. Doing so requires attention to both infrastructure and affordability.

But the New York State Telecommunications Association suit argues that the Affordable Broadband Act slows down infrastructure expansion by burdening telecom companies; because one third of state households qualify for the low-cost service, the companies would take a financial hit that prevents them from investing in rural infrastructure.

The suit also argues that the federal Communications Act precludes New York State from regulating broadband rates.

Of course, it’s not just rural areas that suffer from lack of service. The education not-for-profit Education Superhighway found last year that 64 percent of offline homes — 18.1 million households containing 46.9 million people — cite affordability, not connectability, as their limiting factor. Only a quarter of households had no access to the internet because of lack of hardware.

In the Hilltowns, both are an issue, and neither more so than the other, as far as can be gleaned from available data.

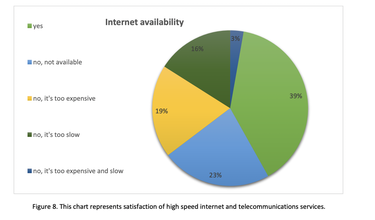

The town of Westerlo recently put together a comprehensive plan that included a survey of around 450 households and found that, while 23 percent of respondents said they had no internet service options available to them, 19 percent said it was available but too expensive, and an additional three percent said it was too expensive and too slow.

A map published by the state earlier this year showed that connection rates on the Hill decreased with income. More than 80 percent of households that earned more than $35,000 had internet access, while only 69.4 percent of households earning between $20,000 and $35,000 had it. For those earning between $10,000 and $20,000, the rate is 35.3 percent.

Although the median income in the Hilltowns tends to look higher than expected, many households struggle financially.

Former Westerlo Supervisor Bill Bichteman told The Enterprise in 2021, that while the town “has, on paper, a median income which is above what they consider to be low and moderate income,” the majority of the town fall within the low-to-moderate range. Some very expensive homes in Westerlo, often from residents who started as summer visitors from New York city, skew the income average.

In the Berne-Knox-Westerlo school district, 39 percent of students were considered economically disadvantaged in the 2020-21 school year, meaning they qualified for reduced lunch prices, according to the New York State Education Department.

For reference, the upper-tier income eligibility for the federal reduced-price lunch program for the 2020-21 school year was 185 percent of the federal poverty guideline, totaling $23,606 for a single-person household, and increasing by $4,480 for each additional person.

For the 2022-23 school year, the rate is still 185 percent of the federal poverty guideline, totaling $25,142 for a single-person household, and increasing by $4,720 for each additional person.

Private vs Public

As for infrastructure investment and the role private companies play, it’s not so simple as ensuring that these companies have enough money to expand into rural areas. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, internet service was generally acquired at the full rate, and yet hardware is still an issue on the Hill.

Westerlo was recently successful in acquiring an enormous federal grant — $1.6 million — to install broadband within the town. It’s public money, according to Hudson Valley Wireless General Manager Jason Guzzo, that will make the biggest difference for rural communities, whose low population densities make broadband investments unappealing to private companies.

“It is challenging to balance the need for connecting unserved constituents with running a sustainable business,” Guzzo told The Enterprise this week. “Reducing the service price may increase adoption, but private companies cannot install connections for below costs.”

To that end, Hudson Valley Wireless seeks out partnerships with public entities to figure out how to accommodate all the different needs involved.

Although not yet applicable to Albany County because of lack of funding, Guzzo said his company managed to get a grant that lowered the cost of its internet service to $30 for low-income families elsewhere in its service area, which, when combined with the Federal Communications Commission’s low-income internet subsidy of $30 per month, makes service free for those residents.

“For most grant projects, we work on providing a subsidy to construct the network but do not offer additional assistance for low-income subscribers,” he said.

Governments of all kinds have signaled their intention to address the internet problem since the pandemic, and the federal government has invested billions in expansion efforts so far, including direct grants to private companies so that they can expand their services to underserved communities across the country.

For better or worse, the Hilltowns were assigned to SpaceX, which deploys satellite internet service through its Starlink branch. It circumvents the need for broadband, but is expensive and how well it works within the topography of the Hilltowns remains to be seen at scale. In any case, it demonstrates that private companies are not self-reliant in the fight to close the digital divide.

That’s not to say that fully private efforts are nonexistent. Hudson Valley Wireless also works with Microsoft through its Airband Initiative, which is the division the company has devoted to digital equity.

“Microsoft is helping us with funding, access to free and affordable devices, free digital literacy, and digital skilling for the communities,” Guzzo said. “They are also backstopping projects with data and mapping to help target relief to communities.”

One map provided by Microsoft showed a direct correlation between population density and digital equity in Albany County, Guzzo pointed out.

“Broadband is no longer a luxury,” he said. “It is necessary. In my opinion, this is an equity issue; constituents residing in the Hilltowns deserve the same quality Internet as those living in a populated city. Service providers' job is to work … to figure out how to connect them with a quality product at an affordable price.”

Guzzo’s views are similar to those expressed in the complaint filed by New York State Telecommunications Association and the other trade associations, which states, “Broadband providers recognize the need to close the ‘digital divide’ and to ensure that broadband is both available and accessible to all Americans, including low-income households.

“In addition to continuing to build out their networks to reach underserved communities, broadband providers have developed their own, lower-priced offerings specifically designed for low-income households. In addition, broadband providers participate in federal programs that provide subsidies to make broadband more affordable.”