Western Avenue 11-lot subdivision appears poised to clear first hurdle

— From CM Fox Living Solutions submittal to village of Altamont

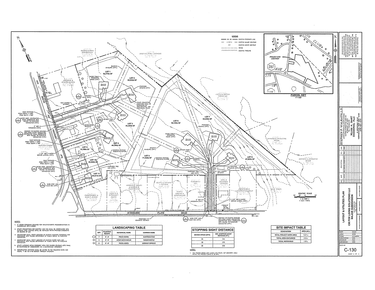

The Altamont Zoning Board of Appeals is being asked by CM Fox Living Solutions to sign off on a variance for a proposed 11-lot subdivision that would allow four parcels off of Schoharie Plank Road West to have about half of the required road frontage that is called for in the village code.

ALTAMONT — Nearly a year after first presenting his development plans to the village, Troy Miller could soon strike a significant task from the to-do list for his proposed 11-lot Western Avenue subdivision.

Miller, by way of his CM Fox Living Solutions LLC, first proposed the project in September of last year. A few months later, in December, he requested a variance that would allow four new keyhole lots as part of the proposed 10-home, 11-lot subdivision (one parcel has an existing home) located on 13 acres bounded by Western Avenue, Schoharie Plank Road West, Gun Club Road, and Marian Court.

The Altamont Zoning Board of Appeals is being asked to sign off on a variance that would allow the four parcels, which would be accessible by a road placed between 115 and 117 Schoharie Plank Road West, to have approximately 16 feet of road frontage, while the village minimum for a keyhole lot is 30 feet. Three properties would be accessed by a shared roadway located between 133 and 137 Western Ave., while another three would be accessed directly from Western Avenue.

At its July 25 meeting, the zoning board made no formal decision on Miller’s variances, but it did appear to indicate that the requests could be granted.

By signing off on the variances, the board would be handing Miller only one approval his proposal needs; it would still have to review the project itself.

What the board would be doing in granting the request is saying that approval of variances alone does not rise to the level of adversely impacting the environment, which is because certain area variances are subject to the same review process used in scrutinizing building projects themselves: the State Environmental Quality Review.

Hyde Clarke, the zoning board’s attorney, told its members as well as meeting attendees on July 25 it was important to understand that issuing a negative declaration on the requests — meaning granting the variances would not a have potentially significant adverse impact on the environment — didn’t mean there would be no impact.

He said, “It only means that, overall, in the board’s understanding of the proposal, the proposed impact does not rise to the level of requiring a full Environmental Impact Statement,” an in-depth review of a project’s potential effect on its surroundings.

Clarke pointed out that, by issuing a negative declaration, the board could acknowledge all its areas of concern and stipulate, for example, that further mitigation planning was necessary or more design work was needed.

Following the closing of the proposed action’s public hearing on July 25, zoning board Chairwoman Deborah Hext asked her board if it felt ready to take action on the variance requests.

“So do we feel we have enough information to make a negative declaration at this point? Meaning that there’s not going to be a huge environmental, or a significant environmental impact going forward?” she asked.

Barbara Muhlfelder was the only board member to make her thoughts known. “I don’t feel that it’s negative,” Muhlfelder said, referring to the type of determination the board will have to make on the request. “I’d say it’s positive. I think there are too many issues involved.”

Muhlfelder said she had concerns about water and drainage on the site, both issues that have been brought up by project opponents since the development was first proposed. More homes, along with their corresponding infrastructure, mean less impervious surface in an area of the village, which could mean more stormwater runoff heading into local waterways.

Over the past months, residents and board members have brought up the issue of flooding in the area around the proposed development, which is close to but not in a 100-year floodplain.

Part of the proposed development is to be accessed from Schoharie Plank Road West, which is located in the 100-year floodplain. This was a cause of concern for the board because it could potentially impact drainage flow, which was an issue because being able to maintain drainage patterns would prevent downstream flooding.

Schoharie Plank Road West resident Deb Johnson recounted for the board at its June meeting more than a few examples of her neighbors dealing with being flooded out. At earlier meetings, neighbors mentioned having seen sediment flowing into Fly Creek during heavy storms, which was said to be an indication of already-present runoff issues.

Stormwater management has been brought up regularly by the board at the half-dozen or so meetings during which Miller’s proposal has been discussed. At its February meeting, Chairwoman Hext said she had been told by some Schoharie Plank Road West residents that the proposed development area was always wet, but she added, “I don’t know what ‘always wet’ means to anyone.”

“Always wet” to Hext meant the area can’t be mowed. But she also said she didn’t know if the proposed development area was “always wet,” because she hadn’t walked the property.

The board can’t do much at this point in the project to alleviate its stormwater concerns, because, for a mitigation plan to be submitted to the village, the project has to first be granted its variances as well as have its site layout approved by the board.

The village’s engineer, Brad Grant of Barton and Loguidice, did offer mitigation measures the board could impose on the project during the next phase of the application process, site plan and subdivision review.

Grant recommended each lot have a rain garden, which “is a depressed area in the landscape that collects rainwater from a roof, driveway, or street and allows it to soak into the ground,” reducing runoff from the property, according to the EPA. He also recommended a permanent swale, an excavated channel or trench, be installed on the Marion Court side of the development, and would help prevent stormwater sediment from flowing into Fly Creek.

As discussion of Miller’s proposal was winding down, Hext sought to allay board members’ stormwater concerns. “We have to go through SEQR [State Environmental Quality Review] in order to approve or disapprove a variance,” she said. “We have to do that, right? But we’re not approving or disapproving” the actual project.

As the board moves forward with its “review the subdivision application, all of these things are going to come up again,” Hext said, so the key on July 25 was to identify areas of concern, note them in the negative declaration, and build in requirements for appropriate mitigation measures during final design.

And then, if “we don’t get satisfactory mitigation or set conditions,” she said, “we don’t have to approve it — we’re not approving it now.”