State’s RAPID Act is a push against NIMBYism

ALBANY COUNTY — In April, New York State passed the Renewable Action Through Project Interconnection and Deployment (RAPID) Act through its budget, making it easier for transmission-line projects to be built in the state by shifting the Office of Renewable Energy Siting, which handles those projects, from the Department of State over to the Department of Public Service.

This is, on its face, a relatively simple change done in the name of bureaucratic streamlining and in service of the state’s wider renewable energy goals, which in turn are aligned with a global mission to slow the existentially-threatening effects of climate change.

As the law itself puts it, “such a transfer would combine the long-standing expertise of DPS related to transmission siting, planning and compliance with environmental and reliability standards with ORES’s expertise related to the siting of renewable energy resources and, in so doing, create synergies, and otherwise provide for more efficient siting of major renewable energy and transmission facilities.”

Rural lawmakers, whose districts are often prime regions for renewable energy development, were swift to criticize the law, arguing that, by streamlining the permitting process, the state government was positioning itself to ignore the will of residents who they say are most affected by siting decisions.

This critique highlights the unspoken obstacle that the law appears designed in part to avoid: NIMBYism.

Background

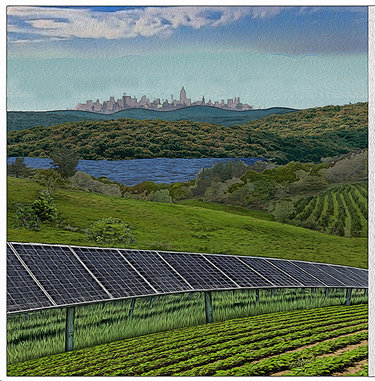

An acronym for “not in my backyard,” NIMBYism describes opposition to any kind of project that stems from quality-of-life concerns. Specific issues brought up during planning processes might be noise from wind turbines, the ugly appearance of a solar field, or reduced property values resulting from either.

“Rural communities in Michigan, New York, Ohio, and other states are blocking wind and solar projects and battery plants because they are concerned about their neighborhoods, view sheds, and property values …,” writes the Institute for Energy Research. “Rural Americans are fighting back against wind, solar and battery plant projects because they want to retain the character of their townships, ranches, farms, waterways and villages, and there is growing concern about the downsides of the land demands of renewable energy.”

In covering local public hearings on renewable energy projects, The Enterprise has quoted many opponents of those projects who insist that they recognize the need for green energy but are distraught by the local impacts.

Because these concerns are typically more concrete and immediate, they can be felt viscerally, and often put people who support a certain type of development in general at odds with the particular one being proposed in their backyard, hence the term. And the viscerality and social contagion of the fears can create fairly well-organized opposition efforts, hence the -ism.

Writing in an op-ed for the New York Times earlier this month, the founding executive editor of the climate-change media company Heatmap, Robinson Meyer, argued that renewable-energy opponents also have a fairly easy job, needing not to argue in good faith on the merits of a project, but only to raise speculative concerns and demand more and more environmental analyses until a project is all but paralyzed.

“Behind countless major infrastructure projects is an expensive war of attrition,” he said.

And studies don’t necessarily do anything to ease the public’s mind, or even those of the nominally better-informed planning officials.

In 2022, The Enterprise reported how the Albany County Planning Board had issued disapproval for a solar project in Knox based in part on the planning board’s own misinterpretation of a county law protecting certain viewsheds, as confirmed by the author of that law, William Reinhardt, and disregard for a sightline study that showed the project wouldn’t be visible from that viewshed to begin with.

The irony that’s often at the heart of NIMBY movements, and the tactics by which those efforts prosper, may be why they bring so much frustration out of purer advocates for the projects most affected by them.

And, increasingly, the gloves are coming off.

States stepping up

Although NIMBYism has its roots in the renewable energy sphere — beginning during a push in the 197os for nuclear energy — housing is where it’s discussed most frequently in the mainstream.

Democratic California Governor Gavin Newsom, who is currently dealing with the worst homelessness crisis in the United States, told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2022 that “NIMBYism is destroying the state,” thanks to the opposition to affordable housing development launched by generally wealthy and ostensibly liberal communities.

His response to that threat, as he sees it, was to get the state involved in local processes, auditing the city of San Francisco’s sluggish development processes, and passing a measure that will require local governments to dedicate a certain amount of their budgets to factors that contribute to the homeless crisis, like mental health and housing.

“The issue of homelessness is mostly a local issue,” Newsom told late-night host Seth Meyers last year, when asked about his thoughts on battling his own liberal ilk. “It’s a county and city issue. It overwhelmed the cities and the counties, so the state has asserted itself.”

Although the dynamics of decision-making around renewable energy and the homeless crisis are different in some key ways, they have in common the fact that local decisions leach upward, and none more so than those to do with climate, which may explain the way New York’s emboldened approach to renewable energy development mirrors California’s to homelessness.

Stephen Jarvis, in an award-winning research paper on the costs of NIMBYism published through the University of California, Berkeley, wrote that local planning officials are generally more moved by residents’ concerns than concerns of society at large, thereby giving NIMBY objectors outsized influence despite the fact that, with regard to climate, the projects are not solely within their jurisdiction.

“That local officials pay attention to local factors is unsurprising,” Jarvis wrote. “In fact, there is a compelling argument to be made that local policymakers are in fact making optimal private decisions for their respective jurisdictions. The key here is that what may be optimal for a given local area can in aggregate create harmful outcomes for society as a whole.

“In the context of renewable energy, I find that refusing a renewable energy project to avoid adverse local impacts may indeed benefit local residents. However, the resulting underprovision of renewable energy or the shift in development to more remote, more expensive projects, raises the costs of climate change mitigation for society as a whole.”

Serious concerns

It can’t be ignored, however, that despite the frivolousness implied by the term NIMBY, it does include some portion of concerns that are very serious, or connect to larger feelings of disenfranchisement.

Returning to the term’s roots in nuclear development, it goes without saying that although nuclear fusion is, under perfect circumstances, an ideal source of energy, the local impacts of nuclear power plants aren’t measured just in gradations in quality-of-life, but in the difference between life and death.

Fortunately, there is no widespread devastation that’s threatened by solar and wind energy, wherever it’s located.

But unlike housing, where the sides can be reduced down to moneyed land-and-home-owners versus those in need of those things, and the issue maps cleanly onto basic moral frameworks, renewable energy advocates are tasked with asking rural areas — which, due to their low populations, wield less political influence — to buck up and wind back the effects of all the emissions that are pouring out of large cities that so often dismiss those communities.

The result is opposition that is that much more emotionally charged.

Republican New York Assemblyman Chris Tague, of the 102nd District, wrote in a statement in April that the RAPID Act essentially forces rural New Yorker to serve as a battery for New York City’s energy needs, claiming falsely, but no doubt potently, that the measure will put farmland at risk, put farmers out of work, and cause New Yorkers to all but starve to death.

The fact is, New York is highly aware of the value of its farmland — the industry generated $8 billion in 2022, and was a top-10 producer in 30 commodities — and the RAPID Act creates a farmland protection working group made up of agency leaders, local officials, and local protection boards to ensure that farmland is preserved.

The state also already disincentives development on prime soils, successfully reducing the footprint of projects on these soils over the past few years, as The Enterprise previously reported.

The Enterprise has also reported that there is a rising interest in agrivoltaics — systems where the functions of solar and agricultural farms are combined for mutual benefit — and that farmers are finding a windfall in their lease agreements with solar developers.

Nevertheless, Tague wrote in his statement, “If farmers don’t have land to work on, we’re left without the product they produce, plain and simple. Crops could grow on the land being overrun by solar farms. Animals could graze the grass if it weren’t overrun by renewable energy plants. And farmers could continue to work in this state if they weren’t considered a lesser priority than renewable energy for residents in New York City to enjoy.

“This state continues to strangle the one industry we all rely on. Not only that, but the programs they implement in place of agriculture do not benefit the people that lose access to the very land being taken over by these new energy farms — there’s no financial benefit to the host communities, or to the local taxpayers. I hope and pray my legislative colleagues understand this mantra soon — No Farms, No Food — because if they don’t, my great fear is that we would be left without an agriculture industry to employ and feed people in New York.”

Although misguided, Tague’s position likely reflects general apprehensions about the state taking over, and the general difficulty faced by those who are trying in good faith to balance out local needs with the global good.

Writing for the Sierra Club, Jim Motavalli notes that, despite the harms posed by NIMBY objectors, they still remind decision-makers of the need to engage with local communities so that what needs to be done is done as harmlessly as possible.

Motavalli argues that this will require advocates to do their best to expand the scope of the opposition, particularly when it comes to renewable energy.

“They could make it clear that massive change is coming, the severity and scope of which will be determined by how we choose to respond now — as individuals trying to preserve comfortable lives and lovely sight lines for the rest of our days or as communities trying to maintain a livable planet for our grandchildren,” he writes. “There will be painful trade-offs; that much is assured. Our task is to agree, together, on which ones we can live with.”