‘We’re all in this together; let’s figure out what to do’

Talking to Bruce Dearstyne is, for me, like taking a tonic.

Dearstyne is an historian who spent the bulk of his career as the program director of the New York State Archives.

He grew up on the Berne farm that has been in his family since 1899. “It was hard but wholesome,” he said of farm life.

He was surrounded by history in Berne. Next to his school is the Lutheran church where, on July 4, 1839, a “Declaration of Independence” was issued by tenant farmers to defy their patroon landlord, demanding lower rent and the right to purchase the hilly farms they were leasing.

Dearstyne revered his teachers at Berne-Knox and has written on our pages about the excellent education he received there.

“They were determined that kids would learn,” he said. “They would push you to excel.”

And excel he did. He was the first in his family to go to college.

He studied history at Hartwick College in Oneonta and then got a fellowship to study at Syracuse University, writing his doctoral dissertation, later published as a book, on railroad regulations in New York state in the Progressive Era.

He had delved into the Progressive Era as an undergraduate, writing his senior thesis on Alton B. Parker, New York’s Progressive Era judge, defeated in his 1904 presidential run against Theodore Roosevelt.

It was while he was doing research on that thesis, in the stacks of the State Library in the old Education Building, that he met the librarian who would become his wife.

“She was shelving books,” Dearstyne told me this week, “and checked to see if I had a pass. We discovered we had a lot in common, starting with a love of books.”

One of their daughters is now a librarian and their grandson, a senior in college, is planning to be a history teacher as Dearstyne himself was at the start of his career.

I was talking to Dearstyne this week because he has published his third book in two years and this one is dedicated to his wife, Susan V. Dearstyne, who edited and indexed it.

“Her patience, wisdom, insights, and encouragement have sustained my life and work for five decades,” writes Dearstyne.

The couple live in Guilderland and Dearstyne has written for our pages insightful commentary on the town’s development as it updates its comprehensive plan.

He looks at the world through the lens of a historian.

And that is why, for me, conversing with him is like taking a tonic. A tonic, of course, as we use the word today, is a sort of elixir, which invigorates and refreshes.

The word comes from the Greek tonikos for “stretching” and, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, was first used in the 1600s to mean “maintaining the healthy firmness of tissues; increasing the strength or tone of the system” and then was extended in the 1700s to mean “bracing, invigorating” on the notion of “having the property of restoring to health” — also extended to mental and moral health.

When I talk to Dearstyne, my mind stretches.

We were talking this week about his just released book, “Progressive New York: Change and Reform in the Empire State, 1900 - 1920: A Reader.”

Before I called him, I was in a Slough of Despond over the state of our nation and my inability to help change course — the impending doom of climate change, the eroding rights of women, the dissolution of democratic principles, the deep division and polarization even among people who once were friends; the list goes on.

But my mind both stretched and relaxed as I read Dearstyne’s book and talked to him about it.

He has told me before that in our modern era, what we learn is often filtered through what other people say and think. As an archivist and historian, he values original sources.

His book compiles 72 different documents written in the first part of the 20th Century, with introductions, for context, written by Dearstyne. He is letting the people of that era speak for themselves.

In this modern era with 24/7 news cycles and constant social media posts, with information coming at us constantly — Dearstyne termed this “so much noise” — it is refreshing to read the words of progressives from a century ago.

They were journalists, pejoratively called muckrakers; activists; observers of the time, all pushing solutions that hadn’t been tried before.

The Progressive Era, Dearstyne explains, was a search for order coming out of the self-centered hyper-individualistic, laissez-faire doctrine of the Gilded Age.

There was a moral awakening of the need to work for the betterment of society; this awakening was embraced across political parties and economic classes.

Whereas people had formerly been living on farms and working in small shops, now they were employed by large industrial companies.

We are now in a similar societal seachange wrought by the internet — which has the power to bring us together but has isolated us in silos — with artificial intelligence promising more rapid shifts ahead.

Asked how our attempts at progress are different now than a century ago, Dearstyne said, “Right now we seem to be very divided. There seems to be a lot of stereotyping and shouting rather than dialoguing.”

He noted that socialists didn’t get far in the Progressive Era and anarchists got nowhere. But the two major political parties changed course, going from largely conservative to progressive.

“There was much more of a sense that we’re all in this together; let’s figure out what to do,” he said.

In New York City, there were five major newspapers with wide circulation and also journals and magazines that would “investigate and expose,” said Dearstyne, coalescing the public as well as moving politicians towards change.

“Now, we have a lot of polarized media,” said Dearstyne. Nationally, one side is portrayed as good and the other without merit as people gravitate towards sources with which they already agree.

In the Progressive Era, Dearstyne said, even rivals in the state legislature were civil. “They knew they had to compromise to get things done.”

But division, he noted, has been part of our nation since its founding. In 1776, John Adams said that a third of the colonists wanted independence, a third did not, and a third were undecided.

“And yet we came together,” said Dearstyne.

He noted cyclical divisions in our nation’s history, most notably the Civil War, but also in the 1890s, the 1930s, and the 1960s.

“I’m optimistic,” said Dearstyne. “We have seen analogous situations to today but our country always comes through.”

Dearstyne noted parallels between essays in his book with what is happening today. Women’s rights were an issue and, while women couldn’t vote until the 1920s, women’s advocacy and political work led to suffrage.

Minorities, too, struggled for equity. In 1920, over a third of the population of New York City wasn’t born in the United States. “It’s a constant struggle, a constant risk of backsliding,” said Dearstyne. His advice: “Don’t give up; get organized … You just have to keep going.”

Walter E. Weyl, a journalist and economist, wrote in his 1912 book, “The New Democracy” of a “social surplus,” economic abundance generated by American enterprise, that would allow for gradual reform.

“They felt we can do better than this, progress is possible; we’ve got the resources” said Dearstyne. Rather than the wealth being concentrated as in the Gilded Age, there was a sense of “we can all advance together,” he said.

As rural America faded and the empty spaces filled, Dearstyne said, “People felt bewildered. They didn’t know where to put their faith.” What came to be called the middle class was forming, embracing the philosophy, “We can all rise together.”

“They were improvisational and pragmatic, not ideology-driven,” said Dearstyne.

A lot of what Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party, which lasted just one year, 1912, advocated for — women’s suffrage, more business regulation, health-care reform — was achieved in the 1930s. “A lot we haven’t achieved yet,” said Dearstyne.

While each state was dealing with the upheaval of industrialization, many states looked to New York as it had to deal with a number of the issues of the era first. Change bubbled up to the surface from the states. “Today, it’s about who is going to control Congress,” said Dearstyne.

Dearstyne hopes that people listening to his library talks or reading his book will have some a-ha moments — “a lot of little lightbulbs going on.”

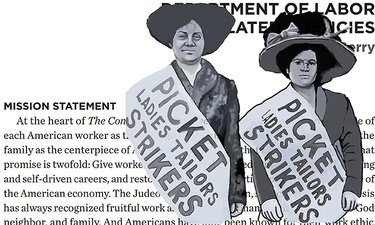

His book is illustrated largely with period photographs from the Library of Congress. The cover shows two stalwart well-dressed women — topped with large fashionable hats — wearing signs declaring Ladies Tailors Picket Strikers.

Dearstyne notes they don’t look like textile workers, but rather like middle- or upper-class women who joined picket lines because women could be roughly treated by police, and these women would supply money for bail.

“These folks don’t look angry,” he said. “Their facial expressions say, ‘I’m not happy. I’m damn well going to stay here. I will not be moved.’”

Typifying the participants in the Progressive Era, he said, “They push boundaries but don’t break boundaries. They make things better without tearing things down.”

I believe we could learn from our sisters of a century ago.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor