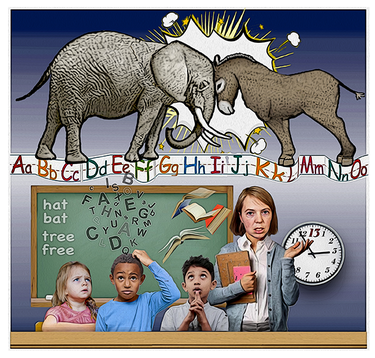

Learning how to read should not be political

Opinion is like a pendulum and obeys the same law. If it goes past the centre of gravity on one side, it must go a like distance on the other; and it is only after a certain time that it finds the true point at which it can remain at rest.

— Arthur Schopenhauer

The pendulum from whole to parts learning has swung again.

The debate is as old as our nation.

In 1990, we covered a conference on reading hosted by teachers at Berne-Knox-Westerlo. The keynote speaker was Richard L. Allington, president of the International Reading Association and also of the National Reading Conference.

He had started his career as a teacher in a rural school before becoming a university professor (then at the University at Albany, now a professor emeritus at the University of Tennessee), trainer and researcher, and author of scores of articles and a dozen books.

The question has always been, Allington said, whether to start with little pieces and get to books or to start with books and get to the little pieces — and the pendulum swings every 30 years or so.

As far back as the earliest Massachusetts colonies, educators debated whether children should read from the Bible first, or be taught the alphabet first.

Along with the shift from whole to parts learning, Allington said, there has been a shift in emphasis from child-centered programs to adult scientific analysis.

He cited work done by a Victorian committee set up by the National Education Association and headed by Charles Eliot, the president of Harvard. The Committee of Ten found reading instruction and education to be lifeless and dull and recommended child-centered reading in its 1892 report.

By 1910, the story method had become the most popular method of teaching reading. Teachers began with whole stories, then worked down to the page level, then to the word level, and finally to the sound level.

With World War I, said Allington, there was a public outcry over how bad American soldiers were at reading out of which came the first movement for standardized achievement tests and intelligence quota, or IQ, tests. At the same time, there was a movement towards consolidating small schools into large school systems and running them like businesses.

A scientific movement emerged, said Allington, where reading in the same grade was taught at different levels; the thought was it didn’t make sense to hold all students to the same standard. This era saw the beginning of kindergarten and the idea of “social promotion” from grade to grade — not retaining students who couldn’t read.

Public outcry over poor teaching led to the creation of teachers’ manuals, thought to be the best way of reaching the many rural schools, and standardizing teaching methods. There was a shift from oral recitation in the classroom to the use of workbooks.

By the 1960s, starting with parts was seen as the only way to teach reading. The idea of communist influence, Allington said, was tied to a whole-language approach; millions of dollars were spent by the federal government on research to find phonetic sequences with the hope that science would make the schools failure-proof.

In this climate, in the 1970s, Allington tried and at first failed to publish his article, “If They don’t Read Much, How They Ever Gonna Get Good?” In it, he writes, “When reading takes a back seat to skills instruction, one has to ask the age old question about the cart and the horse.”

Once his article was finally published, it was frequently cited as support for a whole-language approach to reading grew.

Locally, we wrote about the whole-language adoption by the schools we cover. In 1992, we quoted an assistant principal at Voorheesville Elementary School, Janice White, saying, “The way kids speak is the way they should learn to read and write.” Instead of learning first letters, then sounds, then words, as in the traditional parts-learning approach, they are exposed to literature first so that they want to learn to read and write, so that their learning is, in the vocabulary of whole language, “purposeful.”

Now, as 30 years have passed, the pendulum has swung the other way. As our reporter Sean Mulkerrin detailed in a front-page story last week, the Voorheesville School Board, in a split vote, adopted a new reading curriculum, the Wonders curriculum, produced by McGraw-Hill.

This replaces the Units of Study in Writing, which Voorheesville Elementary teachers had previously used. The Units curriculum was developed by Lucy Calkins, a Columbia University professor of education, and a leader of the “balanced literacy” approach, seeing children as natural readers. With “science of reading” critics pushing the importance of phonics, Calkins rewrote her materials for kindergarten, first, and second grades, to include phonics, which Voorheesville used.

The McGraw-Hill Wonders curriculum is among the top-10 in use nationwide, used by 15 percent of teachers surveyed by the not-for-profit Editorial Projects in Education, coming in just behind Calkins’s Units of study at 16 percent.

The most used elementary reading curriculum by far, at 43 percent, is Fountas & Pinnell Leveled Literacy Intervention, published by Heinemann, which uses texts that are supposed to be at the right level for students in homogenous instructional groups with predictable sentence structures and pictures that are literal representations of the text; critics say this promotes memorization or guessing based on pictures and that beginning readers should instead sound out words.

“Drawing upon decades of literacy research,” say the promotional materials for the Wonders curriculum, “we built Wonders to deliver high-quality literacy instruction backed by the Science of Reading.” It goes on to say that a love of literacy begins with phonics and it is necessary to “build a strong foundation for success with daily, explicit, systematic instruction.”

We are not reading experts. But we would note, even with the regular shifts from whole to parts learning and back again, that literacy in our nation has improved dramatically over the decades.

In 1870, twenty percent of the United States population was illiterate, according to the National Center for Education Statistics; that number has steadily declined to less than 1 percent.

The split vote on the Voorheesville School Board is indicative of divergent opinions in other schools we cover as it is in schools across the state and nation.

Reading well is a foundation on which all other studies are based so it is essential to learning — and to democracy itself. For a government of the people to work, the people must be able to read — and read critically.

What we like about New York state’s approach is individual school districts make choices on curriculum; yes, standards are set by the State Education Department but there is choice in how to reach those standards.

What concerns us is states that have passed laws requiring schools to use a phonics-based approach to teach reading: Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Mississippi, and Texas. Several more states require teacher-prep programs to instruct candidates on “the science of reading” or to have teachers pass an exam on it in order to teach.

We received a press release last week from Assemblywoman Jo Anne Simon, a Brooklyn Democrat, pushing a bill she will introduce to require the State Education Department to survey New York’s teacher-education programs “to identify the programs that are using evidenced-based practices consistent with the how the brain reads, and the programs that continue to use debunked methods that will ultimately fail to teach our children to read.”

This brings to mind the rhetoric of the so-called “reading wars” of thirty years ago when, as the Editorial Projects in Education put it, “phonics (correlating sounds with letters or groups of letters) became associated with politically conservative ideologies. Left-leaning ideologies were associated with ‘whole language,’ literacy instruction that emphasizes learning whole words and phrases in meaningful contexts.”

Assemblywoman Simon cites a recent report from the National Council on Teacher Quality that shows New York state’s teacher preparation is “woefully inadequate,” she says, and that “the most important pillar of reading instruction — phonemic awareness, the key building block of reading — is in fact the skill least taught to our teacher trainees, at an abysmal 13% in our State.”

Diane Ravitch, a research professor for New York University, wrote for The Washington Post about the founding of the council that issued the report: “NCTQ was created by the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation in 2000. I was on the board of TBF at the time. Conservatives, and I was one, did not like teacher training institutions. We thought they were too touchy-feely, too concerned about self-esteem and social justice and not concerned enough with basic skills and academics … TBF established NCTQ as a new entity to promote alternative certification and to break the power of the hated ed schools.”

Hating colleges and universities that prepare educators, and setting out to break them, does not seem productive to us.

Learning how to read should not be political. And state lawmakers should not be dictating to educators how best to instruct students.