Beacon Island ash landfill to come under new EPA regulations

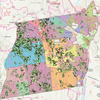

ALBANY COUNTY — The coal ash landfill at the Port of Albany, on Beacon Island, will be subject to new environmental regulations after the United States Environmental Protection Agency adopted a new rule that brings them in line with regulations on currently operating landfills.

The rule pertains specifically to legacy ash landfills like the one at Beacon Island, which closed in the 1970s and was therefore grandfathered out of regulations implemented by the EPA following a calamitous coal ash spill at a Tennessee facility in 2008 that brought the threat such facilities posed to the attention of the federal government, according to the EPA, which carried out risk-assessment studies.

The spill in Tennessee occurred when a structural breach let out 1.1 billion gallons of wet coal ash that covered 300 acres of land, burying and displacing houses and polluting waterways, according to Yale University’s Environment 360 publication and the Southern Environmental Law Center. Although no one was immediately killed in the accident, more than 30 workers who were involved in the cleanup have died while hundreds of others have become sick.

Also known as surface impoundments, ash landfills are not piled high but placed into the ground, where contaminants like mercury, arsenic, and others can leach into the soil and water in the area and cause serious health risks, the EPA says, even without any major breaches like the one in Tennessee.

Legacy fills are particularly dangerous because they are often unlined and unmonitored, and have had more time to contaminate the area around them, the EPA says.

Environment 360 reports that “prolonged exposure to coal ash via air or water can affect every major organ system in the human body, causing birth defects, heart and lung disease, and a variety of cancers. Coal ash pollution has also caused fish kills and deformities in aquatic life.”

The adjacent Hudson River provides drinking water to around 100,000 people, according to the Poughkeepsie Journal, and the EPA says that almost a million households containing over 2.5 million people are within three miles of a legacy fill, and that approximately 75,000 households and 200,000 people are located within a mile.

In 2018, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit struck down the exemption on legacy landfills and ordered the EPA to devise regulations for them.

The new rule intends to make sure that landfills are properly closed and that the groundwater nearby has been treated so that it no longer poses a risk to people or wildlife.

The regulation will go into effect in November this year, and agencies will have until May of 2028 to initiate the closure process, with various deadlines for the planning process in between.

Like many of the other legacy fills on the EPA list, the Beacon Island fill has a “closure status and method” that are “unclear” to the EPA. Port of Albany Director of External Affairs Penny Vavura told The Enterprise that she was working on responding to Enterprise inquiry but would likely not meet the Enterprise’s print deadline.

Notably, the EPA did not include a provision for “innocent owners” in its provision, meaning that all current owners of land containing these fills are responsible for the work, in part because only those owners — many of whom are private organizations — have the right to work on the properties.

Port of Albany, in project documents, has claimed that recent expansions would result in the removal of at least some of the coal ash on the site.

The EPA estimates that the known monetary benefits of the rule will be between $53 million and $80 million annually, accounting for certain reduced health risks, environmental impacts, and need for emergency cleanups, though it notes that the list of factors is “incomplete and omits categories of benefits that are known to be significant” — for instance, lung and bladder cancers caused by two types of arsenic found in the ash, since an EPA report on these substances is still under review.

“These benefits are instead monetized in a sensitivity analysis and are estimated to be $19 million per year when discounting at 2%,” the rule says. “As these benefits are but two health endpoints from a single contaminant, they point to the possible true magnitude of benefits attributable to the final rule.”

The report also notes that nearby home values are expected to increase, reflecting the lowered risk of living in the area of these fills, and have social justice benefits, since many fills are located near or within marginalized communities.

“Although EPA has accordingly designed its proposal based on its statutory factors and court precedent and has not relied on this benefit-cost analysis in the selection of its proposed alternative,” the rule reads, “EPA believes that after considering all unquantified and distributional effects, the public health and welfare gains that will result from the proposed alternative would justify the rule’s costs.”