Confederate in the attic: A southern general from upstate New York

To the Editor:

A rare Civil War photograph discovered in a local collection is helping to reveal new information about New Yorkers who served in the Civil War. While it is generally accepted that about 400,000 New Yorkers served in the Union military forces during the Civil War, comparatively little is known about New Yorkers who fought for the Confederacy.

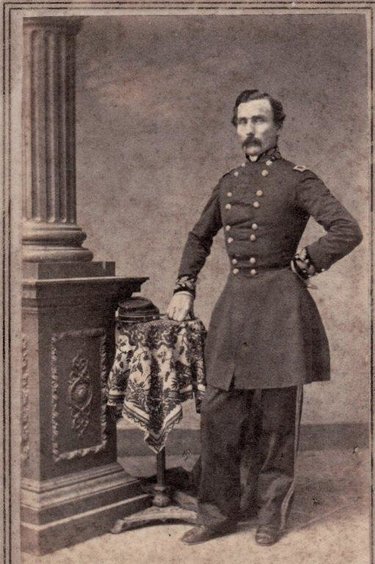

The recent discovery of a portrait of the Confederate general Daniel Marsh Frost provides a fuller understanding of the difficult decisions faced by many when our nation was divided by civil war.

The portrait of General Frost is a type of small paper photograph, known as a carte de visite, that was intended as a sort of illustrated visiting card. Unlike earlier photographic types such as daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes, the small paper-mounted photographs were inexpensive and could be produced in large quantities from glass negatives by photographers during the Civil War period.

These inexpensive portraits captured the faces of loved ones leaving for the war, as well as those political and military commanders whose names were familiar to the public based on newspaper accounts and the letters they received from their loved ones at the front. Photographers were eager to commercialize on the public fascination with those leading the war effort and produced the photographs to satisfy demand. They could be purchased at photographic studios and stationary stores for less than one dollar and were avidly collected by the public and displayed in specially designed leather-bound albums.

The recently discovered portrait of Daniel M. Frost is credited to Edward Anthony, an enterprising New York City-based photographer and equipment supplier, who later gained fame for his purchase of the negative collection of the celebrated photographer Mathew Brady. Anthony’s firm published thousands of Brady’s images in carte de visite format all credited to the original negatives preserved in the “Brady National Portrait Gallery.”

This photograph of General Frost has inspired the discovery of a fascinating story of one of the most controversial officers to serve during the Civil War.

Daniel Marsh Frost was born near Duanesburg, New York. His father was James Frost (1783-1851) and his mother, Mary Marsh Frost (1788-1864). James Frost had a Quaker upbringing and was active in community affairs. In 1808, he built a family home in Mariaville that still stands and is listed on the historic register.

After a successful career as a public surveyor, the elder Frost removed to the Quaker Street settlement near Duanesburg where he farmed and operated a general store. A Whig in politics, he served as justice of the peace and also served three terms in the New York State Assembly.

He and his wife produced 10 children, equally divided between boys and girls. His wife died on Aug. 18, 1864. Both she and the elder Frost are buried under a stone obelisk in the Mariaville Cemetery.

Daniel M. Frost was appointed from New York to the United States Military Academy in nearby West Point and graduated in 1844, ranking fourth in a class of 24. It was a class that included several future Civil War notables, including Confederate Major General Simon B. Buckner, and the Union generals Winfield Scott Hancock and Alexander Hays and the cavalry commander, Alfred Pleasanton.

Like many of his West Point classmates, Frost experienced his first combat service in the Mexican War. During the war, he served under General Winfield Scott in the Army of Occupation in Mexico and received promotion for gallantry in action at the Battle of Cerro Gordo.

After the war, Frost spent part of 1849 as the commissary officer of an immense supply train sent to the Oregon Territory. The following year he was assigned to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, then the largest military base in the west.

After a brief assignment in Europe, Frost returned to the United States. He rejoined his regiment on the Texas frontier. In a skirmish with a Native American raiding party, he was severely wounded and nearly lost an eye.

In 1851, Frost met and married Elizabeth Brown “Lily” Graham. The couple would have 11 children.

Due to economic pressures brought on by his growing family, Frost resigned his military commission in 1853 and became a partner in a lumber mill. He later established D. M. Frost & Co., a prominent fur-trading company operating from Kansas to the West Coast.

Active in politics, he was elected in 1854 to the Missouri General Assembly as a state senator from Benton County and was a strong supporter of the “Central Clique,” a group of wealthy planters active in Missouri state politics. He worked against the Benton faction of the Missouri Democratic Party, and advocated for the expansion of slavery into the Kansas Territory. He served in the State Legislature until 1858.

Frost remained connected with the army by serving on the Board of Visitors for West Point, and was appointed as a brigadier general in the Missouri Volunteer Militia in 1858 by Governor Robert Marcellus Stewart. He was assigned command of the First Military District, which encompassed St. Louis and the surrounding county.

Civil War

It was Frost’s controversial Civil War service for which he is best known. Of the 426 Confederate generals commissioned during the war, Frost is the only one to have been accused of desertion.

Frost was one of at least five Confederate generals known to have been born in New York State. The others were William Wirt Allen, Archibald Gracie Jr., Franklin Gardner, and Samuel Cooper. Cooper, born in Dutchess County, was the highest ranking Confederate general, serving as a top advisor to President Jefferson Davis.

In the early days of the Civil War, General Frost supported the secessionist movement. In February 1861, he enrolled the members of the pro-secession Minutemen organization as companies in a newly formed Second Regiment, Missouri Volunteer Militia.

This was an act in clear violation of Missouri's “official” policy of neutrality. The formation of the new unit appealed to those more inclined to support the Confederacy.

Frost met in secret with the Missouri governor and other secessionist leaders to discuss the possibility of capturing the federal arsenal in St. Louis.

Around the same time, the governor dispatched two members of the Minutemen to meet with Confederate government officials in hopes of securing siege cannon to support their efforts. At the recommendation of General Frost, Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson ordered the mustering in of the Missouri Militia in St. Louis on May 6, 1861, an activation that would allow for a move on the arsenal as soon as the Confederate artillery arrived.

Anxious to acquire the federal arms stored in St. Louis, Confederate President Jefferson Davis agreed to provide the artillery to the Missouri militiamen. The two cannon arrived in St. Louis on May 8. Frost’s soldiers took possession of the Confederate guns and prepared for a siege against the arsenal from a military camp they named “Camp Jackson” in honor of the governor.

Because of the importance of the arsenal stores, there was a small detachment of Union soldiers and loyal Missourians protecting the arsenal. These men were under the command of Captain Nathaniel J. Lyon. After Lyon became aware of the military buildup at Camp Jackson, he moved against the encampment with the intent of arresting Frost’s Minutemen.

After surrounding the camp, the Union troops forced Frost and his militiamen to surrender without a shot being fired. The bloodlessness of the affair did not last long however. As the prisoners were marched through the streets of St. Louis, a violent riot broke out and 28 people were killed. To ease local tensions, on May 11, Frost was paroled and allowed to return to his home.

Although he initially denied involvement in any conspiracy when questioned, Union officers later obtained a letter that revealed that Frost was an active participant in the arsenal plotting.

After being formally exchanged by the Confederacy for a captured Federal officer, Frost left Missouri and traveled south to formally join the Confederate Army. On March 3, 1862, he was commissioned as a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army and assigned to duty in Memphis, Tennessee, under Major General Sterling Price.

He briefly served as a staff officer to General Braxton Bragg, and then in October was assigned to the Trans-Mississippi Department. Frost led a division into action at the Battle of Prairie Grove in the corps of Major General Thomas C. Hindman. On March 2, 1863, Hindman, who was known as a hard taskmaster by the civilian population under his control, was relieved of duty and replaced by Frost in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In August 1863, Frost discovered that his wife and children had been forced from their home in St. Louis because of his Confederate sympathies. After learning that his wife had taken the children to Canada for safety and refuge, Frost sought to join his family.

He abandoned the army without notice or approval, and traveled to Canada. Frost was listed as a deserter by the Confederate Army, and in December the Confederate War Department officially dropped Frost from its muster rolls. Frost remained in Canada for the rest of the war and did not return to Missouri until after the end of the war in late 1865.

Legacy

Following the war, Frost became a farmer on his land near St. Louis. His second wife died in the early 1870s and Frost married for a third time in 1880, this time to a young widow, Catherine Cates (1840-1900), with two children. The couple had two children of their own. In 1875, one of his daughters married into British royalty.

General Frost spent much of the postwar years remaking his biography — simultaneously proclaiming to Unionists that in May 1861 he had not engaged in pro-Confederate plotting, and to ex-Confederates that he had not, in fact, deserted from the Confederate Army in 1863. While Frost wrote many post-war articles attempting to explain his contradictory actions during the American Civil War, his memoirs do not cover much of the Civil War period.

At the age of 77, Frost died at Hazelwood, his estate in what is now Berkeley, Missouri (suburban St. Louis). He is interred at Calvary Cemetery.

He secured significant wealth during his lifetime. Saint Louis University named its main campus “The Frost Campus” to honor the general after his daughter, Mrs. Harriet Frost Fordyce, contributed a million dollars to the university in 1962. Ironically, part of the Frost Campus covers the former “Camp Jackson” militia encampment site that proved so central to the story of General Frost’s military career.

The photographic portrait of General Frost is evidence that history is, indeed, all around us, in both interesting and unexpected ways. The life story of a controversial Confederate general with local connections confirms that.

Bill Howard

Bethlehem

Editor’s note: Bill Howard is the author of “The Battle of Ball’s Bluff: All the Drowned Soldiers,” an account of an early Civil War battle, and he has an extensive collection of memorabilia and artifacts from the war.