Altamont and Voorheesville would feel impact of major rail deal

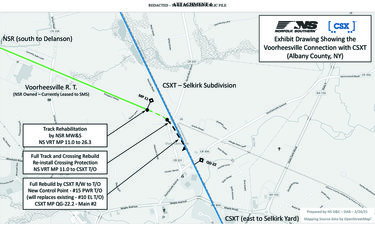

— From the CSX application to the Surface Transportation Board

As part of a new regulatory filing, CSX included information related to routes Norfolk Southern would be using to move a 1.7-mile-long speciality train into and out of Massachusetts. The “Northern Route,” which Norfolk Southern already uses and which limits its ability to move the speciality train, starts at Rotterdam Junction. The “Southern Route,” which begins in Voorheesville, would allow Norfolk Southern to bypass a too-low tunnel on its Northern Route.

ALTAMONT — A 1.7-mile-long speciality train could be moving daily through the villages of Altamont and Voorheesville this time next year if federal regulators OK a proposed deal currently up for review.

The Surface Transportation Board reclassification of a proposed merger between one of the nation’s largest freight carriers and a regional railway company based in Massachusetts has provided new details about the plan — like the eventual rehabilitation of 15.5 miles of railroad track to accommodate a train that’s longer than the two villages it would move through.

In November of last year, CSX reached an agreement to acquire Pan Am Railways, headquartered in North Billerica, Massachusetts, which includes seven of its subsidiaries and their 1,200 miles of collective track.

But Norfolk Southern, the owner of the rail line crossing over Route 146 in Altamont, raised objections to the federal agency charged with oversight of the deal, the Surface Transportation Board (STB), which has economic regulatory oversight over the nation’s railroads.

At issue for Norfolk Southern was its 50-percent stake in a Pan Am Railway subsidiary, Pan Am Southern, a 425-mile system that runs across four New England states and New York.

Norfolk Southern said the deal could be anti-competitive and was “further concerned” about CSX’s “potential use of a voting trust to acquire Pan Am,” a legal mechanism with the potential to relegate Norfolk Southern to bystander status in its own subsidiary.

But the two sides came to an agreement that would allow Norfolk Southern to use 161.5 miles of CSX’s rails to move a 1.7-mile-long speciality train between Voorheesville and central Massachusetts each day.

Upgrades in Voorheesville

In 2000, Canadian Pacific, which bought the Delaware and Hudson Railway Company in 1990, decided that, rather than expending significant resources repairing and then maintaining a railroad bridge over the Normanskill, it would abandon the line it used to move freight between Albany and the Northeast Industrial Park in Guilderland — today, those 10 miles make up the Albany County Helderberg-Hudson Rail Trail. Instead, it would bring back into service the running track between Voorheesville and Delanson, which at that point hadn’t been in use for a decade.

The latest CSX filing states that, “although today there is not an active connection,” Norfolk Southern “will simply need to upgrade” its existing rail “leading to the CSX track in Voorheesville and rehabilitate the existing connecting tracks.”

A map included with the CSX application shows there’s to be a “full track and crossing rebuild,” in effect, reinstalling what was torn out of the area around Voorheesville’s Main Street less than two decades ago, so Norfolk Southern can reconnect to the CSX line running through the heart of the village.

The track work would start at milepost 11.00, which is near Skyler Lane, head along Prospect Street, crossing over the nebulous area the could either be North or South Main Street, at which point the Norfolk Southern line would begin to merge with CSX’s tracks and fully connect near the middle of the triangle of properties bounded by South Main Street, Voorheesville Avenue, and Grove Street.

According to the agreement, Norfolk Southern would gain its track rights on CSX’s mainline at milepost 22.5 in the village, which is located right between the post office and Gracie’s Kitchen at the Voorheesville Avenue railroad crossing, and would extend for 161.5 miles into Massachusetts.

This would allow Norfolk Southern to take advantage of its “Southern Route” trackage rights. With its latest filing, CSX provided regulators with more route information and the financial implications of the changes in train traffic.

Where’s it coming from, going, and why?

In 2014, Norfolk Southern bought the 282-mile Delaware and Hudson line from Canadian Pacific. The acquisition allowed Norfolk Southern to extend its system from central Pennsylvania through Binghamton (where a Norfolk Southern line that runs all the way to Chicago previously terminated) and from Oneonta to Delanson, where the line splits east toward Schenectady and south to Altamont and Voorheesville.

Tucked inside the hundreds of pages of dense legalese — over 99,000 words — that make up CSX’s latest regulatory filing is, appropriately enough, a picture, that answers a question previously posed by The Enterprise to Norfolk Southern: How will the freight carrier get its 9,000-foot-long double-stacked train from wherever it’s coming from to its ultimate destination — 35 miles northwest of Boston, the location of its automotive distribution facility?

To start, the picture, rather a map, to be specific, shows the Voorheesville Running Track from milepost 11.00, near Skyler Lane in the village, north to milepost 26.3, in Delanson, receiving an upgrade.

Norfolk Southern would use this “Southern Route” to move its specialty train.

The “Southern Route” is largely owned by CSX, and starts in Voorheesville, traverses CSX’s railyard in Selkirk; crosses the border into Massachusetts near Pittsfield; follows the approximate path of Interstate 90 until it hits Worcester; and heads northeast toward Ayer, home to a 52-acre freight hub 35 miles northwest of Boston, which is also home to a 13-acre Norfolk Southern automotive distribution facility.

The “Northern Route” begins at Rotterdam Junction and heads east toward Mechanicville; clips the edge of Vermont and enters Massachusetts near North Adams. The route then follows the approximate course of a major state highway, Route 2, toward Ayer. The Northern Route is mostly owned by Pan Am Southern, which is half-owned by Norfolk Southern.

The “Southern Route” would allow Norfolk Southern to move one of its 9,000-foot-long double-stacked trains within 35 miles Boston without having to stop in Saratoga County to take the top stack off the train to make it through a too-low tunnel in Massachusetts.

Norfolk Southern previously told the STB that it needed to obtain the track rights from CSX because they were “necessary to improve [Norfolk Southern’s] ability to move intermodal traffic and automotive vehicles into the greater Boston marketplace.” Intermodal traffic is freight moved in containers.

On a 2021 first-quarter earning call in April, a Norfolk Southern executive told analysts, “We’re expecting intermodal to lead our growth for the next couple of years.”

The company’s intermodal revenue, which accounted for about 27.2 percent of its overall revenue between the first quarter of 2020 and 2021, saw a 10 percent year-over-year increase — while overall revenue increased just 1 percent during the same three-month period.

Also during the April 28 earnings call, Norfolk Southern told analysts that, since the first quarter of 2020, the company had been able to increase train weight by 13 percent and train length by 11 percent.

Freight train lengths have increased significantly over the past 10 years and more.

Two Class I carriers told the United States Government Accountability Office in 2019 that the average length of their trains had increased by 25 percent between 2008 and 2017, from 1.13 miles long to about 1.4 miles and from .92 miles to 1.2 miles long. About 10 percent of Norfolk Southern trains are over 10,000 feet in length, or nearly 1.9 miles.

The push for longer and heavier trains has been part of a broader initiative aimed at up-ending a hidebound industry that had, for the most part, been run the same way for a century.

Under the old system, freight carriers would wait for customer shipments to be delivered to the rail yard, departing only after the cargo had been loaded. The new system, known as “precision-scheduled railroading,” or PSR, is modeled on the commercial-airline industry, with set departure times.

Norfolk Southern in 2019 began reporting to analysts that, by running fewer but longer and heavier trains at faster speeds, its implementation of PSR had already led to more business, which yielded increases in both profit and revenue.

For the two months prior to that April 2019 earnings call, Norfolk Southern’s stock was trading at a median price of $182.53. For the same period this year, that number was $268.25, and investor appreciation of the changes were evident in the headline of a recent story from The Wall of Journal: “Railroads, Growth Stocks of the 19th Century, Are Hot Again.”

Since 2009, when billionaire investor Warren Buffet paid $44 billion for a Class I freight carrier, “the market value of North American railroads has risen sharply,” The Journal reported in early April.

An investment portfolio containing only the stock the nation’s largest freight carriers purchased the day before Buffett made his announcement, would have had a total return of 862 percent, according to The Journal; a similar investment made in a bucket of Standard and Poor’s 500 stock over the same period would have yielded a 300 percent return on investment. The S&P 500 is an index of 500 of the largest companies listed on American stock exchanges.

PSR was cited as a major reason for investor affinity in railroad stock, according to The Journal, as were trains’ “far greater fuel efficiency per ton mile than trucks…”

The STB

In February, CSX submitted its amended application to the Surface Transportation Board, seeking approval to take over the Pan Am Railway and its subsidiaries.

CSX told the STB the deal would be a “minor” transaction because there wouldn’t be any resultant loss of market competition as a consequence of the agreements.

The STB disagreed.

And in March, the regulator redesignated the transaction as “significant” and required CSX to hand over additional information so the STB could “develop a more comprehensive record,” which meant it would take longer to approve the deal.

In its original application, CSX offered its regulator a schedule that would have had the STB making an approval or denial decision CSX’s proposal 180 days after the application was filed, on Feb. 25, with the decision becoming effective 30 days after it was made.

The whole deal would have been wrapped up by the end of September. Under the new transaction designation, the STB won’t hand down its final decision until February 2022.

A transaction is considered “significant” if it does not involve “the control or merger of two or more Class I railroads that is of regional or national transportation significance,” according to the STB. Norfolk Southern and CSX are considered Class I carriers, meaning the rail companies took in nearly $505 million in annual revenue in 2019, according to the STB. Two of the seven rail companies — one is Pan Am Southern, in which Norfolk Southern has a 50-percent stake — slated to be absorbed by CSX are Class II carriers, which means they did about $40 million in business in 2019.