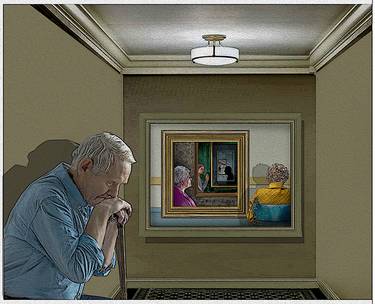

We must mend the social fabric of our nation, one thread at a time

“What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.”

— Kurt Vonnegut, “Timequake,” 1997

Most of us are aware of public health concerns like cigarette smoking, addiction to alcohol or other drugs, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, even air pollution.

These are charted in a recent advisory from our nation’s top doctor, Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy. But what is the public health crisis that is more worrisome by far than any of these?

Loneliness.

The advisory, released on May 2, charts the odds of premature mortality and concludes lacking social connection is as dangerous as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

“Advisories,” Murthy’s report explains, “are reserved for significant public health challenges that require the nation’s immediate awareness and action.”

There has never before been an advisory issued on loneliness.

This one begins with a personal letter from Murthy in which he describes a cross-country trip where he had a “lightbulb moment” as he listened to Americans telling him that “they felt isolated, invisible, and insignificant.”

“Loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling — it harms both individual and societal health,” writes Murthy. “It is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death.”

Of course we had realized some people are lonely. We had just recently interviewed Meredith Osta for a podcast. She is the director of Community Caregivers that pairs volunteers with primarily elderly residents in Albany and Rensselaer counties to provide services like grocery shopping and rides to doctors’ appointments so they can continue to live in their homes.

Although Osta has spent her career in social services, she said of her new job, “It really opened my eyes — I’ll be totally honest — about the number of people living in our community who are totally alone … A lot of us probably are not aware of it.”

She cited the example of a woman who had to ask her landlord if she could use him as an emergency contact “because she literally had no one else.”

Osta told of another Caregivers’ client — “the sweetest, sweetest woman,” in her nineties — who called “because she wanted somebody to go out and just take her on a walk.”

Osta thought, “What a simple request …. It shouldn’t be that difficult.”

The volunteer who then walked with the woman spoke very highly of her. Sometime later, after Community Caregivers had partnered with the Guilderland Public Library to send valentines to Caregivers’ clients, the woman called and left a message after she got her card.

She said, “I’m 95 years old … I want you to know how touched I am because I can’t tell you the last time someone thought of me to send me a card.”

While that story moved us, we still thought of loneliness as largely a problem for elderly people, perhaps especially elderly people who lacked means.

It made us glad we regularly run lists of menus for congregate meals supplied by Albany County or for activities like the recently printed list of trips for New Scotland Seniors or Alyce Gibbs’s column on the activities of the lively Hilltown Seniors.

But, just as Osta’s eyes were opened, Murthy’s advisory opened our eyes to how much wider the problem of loneliness is.

His 81-page advisory, “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation” is packed with data from carefully footnoted studies that show the widespread reach of loneliness — across all age groups, ethnicities, geographies, and demographics.

We felt stunned as we read the advisory but at the same time we felt heartened by Murthy’s call to action.

“Given the profound consequences of loneliness and isolation, we have an opportunity, and an obligation, to make the same investments in addressing social connection that we have made in addressing tobacco use, obesity, and the addiction crisis …,” he writes. “If we fail to do so, we will pay an ever-increasing price in the form of our individual and collective health and well-being.

“And we will continue to splinter and divide until we can no longer stand as a community or a country. Instead of coming together to take on the great challenges before us, we will further retreat to our corners — angry, sick, and alone.”

We had written here about a February report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, based on data from 2021, that showed 42 percent of high school students felt so sad or hopeless almost every day for at least two weeks that they had stopped doing their usual activities.

Nearly three in five teenage girls felt persistently sad or hopeless, double the rate for boys, and a nearly 60-percent increase over the highest level recorded in the past decade.

It would be easy to see these findings as a result of the pandemic but, like loneliness, as Murthy’s advisory shows, the trends may have been made worse by the COVID-induced shutdowns and closures but they predated the pandemic.

Loneliness is not only more dangerous than other public-health threats that we all recognize, it is also more prevalent. About 13 percent of adults in the United States are smokers, about 15 percent have diabetes, about 42 percent are obese — while about half of U.S. adults report experiencing loneliness, with some of the highest rates among young adults.

Murthy’s report details not just individual health problems caused by loneliness but also social and economic problems.

The advisory details the disintegration of social centers like religious and community groups that formerly kept isolation at bay. In 2018, only 16 percent of Americans reported that they felt very attached to their local community.

And in 2020, only 47 percent of Americans said they belonged to a church, synagogue, or mosque. This is down from 70 percent in 1999 and represents a dip below 50 percent for the first time in the history of the survey question.

The advisory also makes the case that online communities and contacts are not the same as those made in person.

In a U.S.-based study cited in the advisory, participants who reported using social media for more than two hours a day had about double the odds of reporting increased perceptions of social isolation compared to those who used social media for less than 30 minutes per day.

Not only do higher levels of social connection within a community correspond to better health and disaster outcomes — recovering, for example, from a hurricane — but they are also associated with lower levels of community violence, the advisory says. It cites a recent study on community violence that showed a one standard deviation increase in social connectedness was associated with a 21-percent reduction in murders and a 20-percent reduction in motor vehicle thefts.

Growing ideological divisions in America are fueling skepticism and even animosity between groups across the political divide, the advisory says, noting that sentiments of enmity and disapproval between Democrats and Republicans more than doubled between 1994 and 2014.

We’ve written many times on this page that a problem has to be acknowledged and understood before it can be solved. Fortunately, Murthy provides us with steps that institutions as well as individuals can take to reduce social isolation.

“We are called to build a movement to mend the social fabric of our nation. It will take all of us — individuals and families, schools and workplaces, health care and public health systems, technology companies, governments, faith organizations, and communities — working together to destigmatize loneliness and change our cultural and policy response to it,” he writes.

The advisory lists six pillars to advance social connection:

— Strengthen social infrastructure in local communities, which includes designing a built environment to promote social connection or investing in local institutions that bring people together;

— Enact pro-connection public policies, such as establishing cross-department leadership at all levels;

— Mobilize the health sector by training providers and expanding public health surveillance and intervention;

— Reform digital environments, requiring digital transparency and establishing safety standards;

— Deepen our knowledge by accelerating research funding and increasing public awareness; and

— Build a culture of connection by cultivating values of kindness, respect, service, and commitment to one another as well as expanding conversation on social connections in schools, workplaces, and communities.

The advisory also provides a detailed list of the ways various stakeholders — from schools and workplaces to parents and caregivers — can advance social connection.

As we read through these recommendations we were flooded with ideas that could play out locally.

Could the committee in Guilderland reworking the town’s blueprint for the future make an environment to provide social connection a priority?

Our local libraries are already community gathering places — what can we do to extend their reach?

How can we better support the community groups — the Scouts and 4-H, the Kiwanis and Lions, the garden clubs and historical societies, the volunteer firefighters and ambulance crews — that, although some of them are struggling, already exist in our community?

But, as often, we will return where we started. Even if you don’t want to volunteer for an organization like Community Caregivers, you can make a difference as an individual by looking in on your neighbor.

As the small staff at the Caregivers’ office listened to the message from the octogenarian who had received a valentine, Osta said, “I don’t think there was a dry eye because it was bittersweet … We were so happy that it made her happy, but, at the same time, it tugged at our hearts because we’re thinking: Just a simple card, you know? …. Something so simple has such a huge impact.”

Osta believes that even small acts of kindness have a ripple effect. We do, too.

“Our individual relationships are an untapped resource — a source of healing hiding in plain sight,” Murthy writes. “They can help us live healthier, more productive, and more fulfilled lives. Answer that phone call from a friend. Make time to share a meal. Listen without the distraction of your phone. Perform an act of service. Express yourself authentically. The keys to human connection are simple, but extraordinarily powerful.”

We need to harness that power if we are to build a better future — one act of caring and connection at a time.