Graveyards should be a public trust

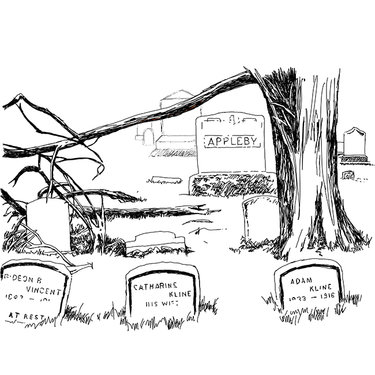

Joseph Hogan communes with the past when he visits the Onesquethaw Union Cemetery in Feura bush.

“I recognize people as I walk through the graveyard,” he said. “I know the history.”

Giving one example, Hogan says that Rushmore Bennett’s grave is there and notes he was the founder of Bennett Hill Farm.

The tall monument in the corner of the cemetery, he said, is for the Meeds, noting it was spelled then with two “e”s. The land for the cemetery came from the Mead Farm, he said. “The rest of what is now the cemetery was a farm field.”

Hogan went on, “When I was a kid, there were piers around the monument with it chained off.”

Hogan grew up in Clarksville, a community he loves. As a member of the Clarksville Historical Society, he was active in researching the hamlet’s history.

“You come across the graves of all the different people who ran the businesses in Clarksville; it was quite a community back in the day,” he told us.

Hogan sees the larger history of cemeteries in New York state, noting burials typically were in small graveyards on family farms or in churchyards until the state passed legislation in the mid-19th Century. The Rural Cemetery Act spurred the development of cemeteries as commercial businesses.

The Onesquethaw cemetery, Hogan said, is not affiliated with a church.

Hogan has been the superintendent of the Onesquethaw cemetery for 27 years.

When he took on the job, he saw that the bylaws were changed so that he is not paid for his work but rather only reimbursed for expenses.

“My mother and father are buried there,” said Hogan. “I’ll be buried there.”

Asked why he has done the work without pay for more than a quarter of a century, Hogan said simply, “I could see they needed the help. They were mostly older.”

Hogan himself is now ailing. “I was knocked back with cancer,” he said. “Three months of radiation knocked me for a loop. With a week to go, I got Covid … It’s been tough.”

Despite his challenges, Hogan keeps on with his superintendent’s duties.

He sells grave sites, at $750 a piece. He also deals with monument companies and funeral homes, arranging for burials.

And he depends on Harold Smith who digs graves, mows the lawn, and does foundation work. “He’s a nice guy,” said Hogan. “He’s undercutting himself to help us; we just don’t have the sales to pay more. It’s not fair to him. He has to make a living too.”

As more and more people are having cremations rather than burials, Hogan said, “It’s not a booming business.”

The Onesquethaw cemetery is closed in the winter. “If we had to plow, we’d be done,” said Hogan.

The town of New Scotland, he notes, has four cemeteries. “We’re all on the verge of failing,” he said.

The cemetery next to the Presbyterian Church, Hogan noted, is helped by income from a cell tower there.

But, while that cemetery is small, he said, “We have a big, big space still open, enough for 100 or 200 years.”

But he worries that his beloved cemetery may not last that long.

“Every year, I think it’s our last year,” said Hogan.

The Department of State is worried about failing cemeteries, too. It reports about 6,000 cemeteries exist in New York with about 1,900 regulated by the New York State Cemetery Board and about 4,000 as religious, municipal, family or private cemeteries.

The department’s Division of Cemeteries says its mission is to ensure that regulated cemeteries do not become a burden on their communities; if they can no longer operate as not-for-profit organizations like the Onesquethaw cemetery, they must, by law, be maintained by the municipality in which they are located.

Years back, the town of Guilderland had to assume care and maintenance for a cemetery in Guilderland Center that could no longer sustain itself.

The state is piloting a program this month with the inaugural Caring for Your Cemetery Day, coming up on Saturday, April 27. We’re pleased that the Onesquethaw cemetery is participating — it’s the only cemetery in Albany County that signed on for the program.

MaryEllen Domblewski, the treasurer of the Onesquethaw Union Cemetery Association, found out about the program because she files an annual report with the Division of Cemeteries.

She checked with the association’s president, Samantha Moak-Bryan, who said to go ahead. “So I did,” said Domblewski.

Like Hogan, Domblewski has a personal connection to the cemetery. “It’s right around the corner from my house,” she said. Her stone house, built in 1807, is where her grandfather was born and where he died at the age of 100 in 1995. Her father and grandfather both served on the board before her.

We applaud her efforts and urge volunteers to participate in Saturday’s clean-up as outlined in our story last week.

While Caring for Your Cemetery Day is a step in the right direction, the problem of course is much bigger than that. As Hogan noted, fewer Americans now choose to be buried.

According to the National Funeral Directors Association, last year, the cremation rate reached 60.5 percent, with a forecast that the national cremation rate will reach 80 percent or higher by 2035. That rate has been rising steadily from 3.56 percent in 1960.

The reasons for rising rates of cremation are diverse. Money is the leading reason, according to the Cremation Association’s annual report, since the cost is roughly a third that of a burial.

As families have scattered and are less likely to live near a central burial place, ashes have become popular. Cremation is considered by many to be more environmentally friendly.

Also, there has been a change in some churches’ stances on cremation. In 1963, the Roman Catholic Church lifted its ban on cremation and then, in the 1990s, allowed cremated remains to be present at a Catholic funeral.

A study by the Scripps Howard News Service that showed the states with the higher rates of church attendance generally have lower rates of cremation. Nationwide, fewer people are attending church. States with large numbers of evangelical Protestants who believe in the resurrection of the body tend to have lower rates of cremation.

Jewish tradition, based in the Torah, does not allow embalming and forbids a body to remain unburied overnight.

The highest cremation rate, worldwide, is in Japan at over 99 percent. India also has a high rate, over 85 percent, as Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains typically cremate their dead.

Americans follow many different faiths and hold many different beliefs. There is no right way to mourn; it is a personal choice.

But it can be instructive to look at our history as we consider our future.

Graveyards should be a public trust. New York, like many other states, should have laws to protect the dead and buried. Failing that, communities should gather, as people are in Onesquethaw, to preserve and honor their past.

We’ve used this page before to call on our towns and their historians to catalog the many small and often obscure graveyards in our midst.

It’s not unusual for a farmer to come across a broken gravestone while plowing a field, or for a worker putting in a septic tank for an old farmhouse to unearth a grave. These people mean no disrespect; there’s simply no way for them to know where a grave site is.

We urge our towns to view their graveyards as a resource rather than just a burial ground. School children could take field trips there to learn about their town’s history much as Hogan reads the markers in the Onesquethaw cemetery and can recall the history each represents.

Mourners know the value of visiting a gravesite. But what about graves of generations past, when no family comes to visit? That’s when neglect often sets in.

Cities like Boston and Philadelphia that have wisely maintained their historic burial grounds are a beacon for visitors who learn about our nation’s history as they visit the sites.

We could do the same thing here.

The pages of our paper for the last 140 years have, for example, chronicled the burials and gatherings that took place at Prospect Hill Cemetery in Guilderland. When the town was celebrating its bicentennial, the late Alice Begley, town historian, looked for a center in sprawling suburban Guilderland in which to hold a ceremony; she settled on the cemetery.

There, where many in years’ past had assembled to hear speakers talking from the porch of the Victorian caretaker’s cottage, a more modern gathering was held.

Begley emulated the sort of get-together that, in 1890, saw Guilderland poet Magdalena L. LaGrange read her tribute to the fallen Civil War soldiers while surviving members of the Grand Army of the Republic listened: “They died — they rest in tranquil peace — and we our tributes pay/ The flowers fair we place with care o’er where our soldiers lay.”

No one comes now to weep for a personal loss at the Civil War monument in Prospect Hill Cemetery — the children and grandchildren and great-children of those soldiers are dead now too. But the obelisk still stands, as the other markers stand — a testament to our history.

Begley herself is buried there now, next to her husband.

As we visited her grave, we recalled her telling us, “I can remember going early to a cemetery where my grandparents were buried and we would pack a picnic and sit around for several hours,” she said. “Once in a while, somebody would say, ‘Don’t walk on Grandpa.’”

We’d like to revive the tradition of visiting graveyards — even if we were not acquainted with its occupants in our lifetime. In a rapidly developing town like Guilderland, a cemetery is an oasis of green, a place for reflection and, ironically, for revitalization.

In modern mobile America, many of us may not live near the cemetery where our ancestors were buried. But we could still care for those in our midst, in the place where we live here and now.

Death is a part of life. Each of us knows that we and everyone we love will someday die. We should care for the graves of those who died before us. It is the duty of the living to care for the dead, and we will be the richer for it.