Altamont was a jewel of a village set off in a beautiful garden until the 1950s brought a countryfied version of suburban sprawl

When I was a child in the 1960s, Altamont meant cows and farms, hayfields and apple trees, old houses and open spaces. We had moved from the village mid-decade, but we never really left it. We’d head back to the village at every opportunity — to visit friends, go to church, or often just to “take a ride.”

The drive out from the city line through Westmere and Guilderland took us past the subdivisions, strip malls, and car washes that characterized the eastern end of town. But turning left on Route 146 took us to another world. The old-fashioned “Mom and Pop” vegetable stand near the corner set the tone. We were now in the country. Subdivisions gave way to open spaces; streams and parklands replaced fast-food joints and parking lots.

An occasional farmhouse dotted the scene, but it was mostly fields and silos until we crossed the big hump of a bridge over the tracks into Guilderland Center. There were houses and stores and churches there, of course, but this was clearly a country hamlet. The Victorian houses were all in a row, compact, contiguous and neat and hardly a one that was built after 1880. There was no hint of sprawl.

From here on out, the Helderberg escarpment dominated the view, looming to the west across the open fields, defining the scene as it had done for centuries. It was easy to see why native Mohicans were drawn to its cliffs, easy to understand why the first white travelers on this road called the escarpment “Helderberg,” which in their Germanic tongue means “bright mountain.”

Heading on beyond Guilderland Center, we passed an old tavern, a small hardware store and some hilltop cemeteries. Then came the big farms. Neat, uniform rows of apple and pear trees filled the fields, set off by huge, dark colored barns with the invariable white farmhouse set back from the road.

These barns and houses were large and prosperous looking, not downtrodden. It was clear that the owners were “gentleman farmers’’; usually lawyers, doctors, or politicians from Albany, men of means who found the countryside around Altamont such an attractive place for a country estate.

We knew we were almost in Altamont when our mom quizzed us as to whether the cows in John Armstong’s fields were standing upright or laying down. She grew up on a dairy farm in the village and this little game was her way of teaching us old-school farmers’ meteorology (cows laying down meant rain on the way!) It was also, no doubt, a way to connect us to an agricultural heritage that was rapidly disappearing.

An open landscape of trees and orchards

Like most of upstate New York, the land around Altamont was cleared of forest by the early 1800s. The landscape was much more open than today. By my time, the forest as such was long gone, but trees, in groves or standing as individual specimens, were still a notable feature of the local landscape.

Certain iconic, old-growth survivors were known and beloved by all. When felled by storm or disease, their demise was covered as news in the pages of The Enterprise!

Today, the roadside and remaining fields are more likely to be filled in with shrubby, weedy indifferent growth. But back then, majestic hemlocks and sugar maples stood out against the backdrop of cleared fields and open vistas.

Lineal groves of oaks and maples hugged the old stone walls and snaked along the hedgerows that divided one old farm from another. Here and there was a standout, growing thick and solitary in the middle of a farm field, branches spread wide like an open umbrella, affording a welcome refuge for those weather-forecasting cows.

Being surrounded by fields and trees was not particularly unique to Altamont; most small villages throughout upstate New York were similarly framed. What made Altamont different and all together more beautiful were the type of farms and trees that encircled it.

Altamont could be called a village in a garden because it was surrounded, on all sides, by a multitude of productive orchards featuring tens of thousands of fragrant, flowering apple, pear, plum and other fruit trees. Arrayed with precision and eye-pleasing symmetry, the neat rows of fruit trees rolled with the contours of the land. The whole scene was perfectly framed with the dramatic cliffs and seasonal waterfalls of the Helderberg forming a picturesque horizontal backdrop.

Fruit and flowers everywhere

Today, there remain a few orchards with a handful of vistas that still provide a modern viewer a sense of what all of this once looked like. However, the modern orchards, beloved as they are, account for but a fraction of the orchard acreage that once dominated and defined our landscape.

A quick historical tour proves the point: Beginning to the south, the Voorheesville Road was once lined with fruit, from the large-scale operation at Congressman Peter Ten Eyck’s Indian Ladder Farm to Oakley Crounse’s more modest 20-acre peach orchard on the outskirts of the village.

On the hill above Altamont, Albany Mayor John Boyd Thacher maintained a mixed fruit orchard at his palatial estate on the corner of Leesome Lane. Across the road, County Clerk W.D. Strevell planted more than 3,000 plum trees leading right to the front door of his center-hall stone Colonial.

North and east of the village the summer estate of Albany physician D.H. Cook featured over 2,000 apple trees as well as 1,100 pear and plum trees on the property that later became Altamont Orchards. Eventually this one orchard grew to over 400 acres in size.

Closer to the village, near Gun Club Road, State Treasurer Benjamin Knower maintained a commercial orchard that was later enlarged under the ownership of his son-in-law, William Marcy, who served as governor and later United States secretary of state. This orchard covered most of what is now the lower end of the village.

The heaviest concentration of orchards was found on the approaches between Altamont and Guilderland Center. Peter Severson’s “Fair View” Farm near the corner of Hawes Road specialized in peach trees. Severson and his partners set up a seed company and sold his products across the nation.

One of the largest orchards was located along Route 146 and Hurst Road, where the Black Creek housing subdivision is located today. A cigarette thrown from a car during the drought of 1947 ignited a huge wildfire that destroyed this orchard and threatened the destruction of Guilderland Center itself.

State Police ordered all the residents of the hamlet to evacuate and enlisted every man, along with passing motorists, to halt the blaze. More than 200 men fought 30-foot flames.

“It looked like a ball of fire rolling toward the village,” said Fire Commissioner Joseph Bank.

Seven fire companies ran water lines from the Black Creek and eventually brought the fire under control, but not before it destroyed thousands of fruit trees along with all the orchard equipment and a 200-year-old pre-Revolutionary era barn.

In addition to the large-scale commercial orchards, nearly every smaller farming operation maintained its own apple or mixed-fruit orchards. Even after Altamont and Guilderland Center were developed as villages, orchards persisted within their boundaries.

Helderberg Reformed and St. John’s Lutheran churches were both built on land that had been covered with fruit trees. The same was true of Altamont Village Hall. Topography was no barrier; when the state constructed the new curving road up the Altamont Hill, it requisitioned steep hillside land that had been Mayor Hiram Griggs’s apple orchard.

A feast for the senses

One can hardly imagine the visual and olfactory sensation of tens of thousands of various fruit trees in full bloom all around and within the village. The spring orchard foliage made attractive views sublime.

Today, people still admire our views of the broad Hudson Valley even as the valley and the view have filled in with modern development.

But imagine the perspective a century ago: The same mountain backdrop framing the same broad valley, but in the place of modern subdivisions and industrial parks the foreground filled with a natural carpet of pink, white and purple, the air filled with the scent of tens of thousands of fruit trees, bursting in full May bloom. It must have been breathtaking.

Our forebearers did not take this beauty for granted. In the May 11, 1894 edition of The Enterprise, the editor noted, “Nature now appears at her best. The fruit trees are our immense bouquet and a ride through the country is delightful.”

Albany papers of the same era frequently referred to the fruit trees that enhanced Altamont’s natural beauty, noting that the arcadian setting destined the village to become the region’s most favored resort.

The natural setting defines the village

Altamont’s unique and beautiful setting is what drew people here in the first place. The Mohicans made the first paths here not to chase game or to pass on through to the west. To them, high ground was sacred and this place, being the highest ground in their domain, was the destination.

Later, the setting drew wealthy Victorians, versed as they were in the romantic and restorative effects of nature at its finest. For Altamont, the setting was the reason for its being.

The open vistas and cultured landscape around Altamont were noteworthy on their own but their distinctive beauty also gave definition to the core of the village itself. Like Guilderland Center, Altamont village was dense and compact. In an era long before government mandated zoning, the early residents knew what they wanted and built accordingly.

Most of the early homes in the village were built by retired farmers. After a lifetime of isolation on the farm — where even a trip to the store involved a journey of some planning — they welcomed the opportunity to be social and live in close social proximity to their neighbors. No longer would they have to pay to own and keep a horse.

Living in the village meant they could walk to stores, the post office, school, church, and lodge. If a connection to the wider world was needed, the railroad station was within easy reach. The shape of the village — compact with a defined commercial core — responded to what the residents wanted and valued.

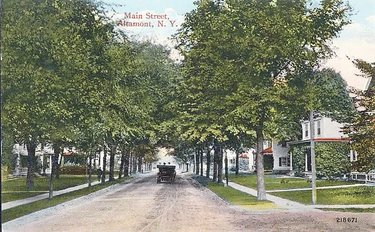

The look of the village also developed in response to what surrounded it. For decades, Altamont village was renowned for the majestic canopy of arching elm and maple trees that lined its primary streets. The cathedral–like effect was made all the more dramatic given the open orchard landscape that surrounded it.

Gothic architects appreciated that the transcendental experience of entering a cathedral could be enhanced or diminished depending on what one encountered before entering the doors. Setting the cathedral apart with open and landscaped surroundings set the stage and enhanced the experience within.

Likewise, experiencing a historic village like Altamont — with its beautiful streets and homes, its park and ornate public structures — was enhanced because you entered it after having first passed through equally beautiful natural landscapes and vistas. Open fields, orchards and the looming escarpment having set the stage, Altamont was defined as a jewel of a village set off in a beautiful garden.

Beginning in the 1950s, the effect was tragically reversed: The canopy of trees along Main Street and Maple Avenue were all chopped down. At the same time, most of the orchards and open fields that surrounded the village were grown over with scrubby, invasive, and untended growth.

The majestic had become mundane. My parents still spoke of the change, with a sense of loss, nearly 60 years after the fact.

Changes to the landscape

The 1950s marked another turning point as Altamont began experiencing its own modest form of sprawl. During the preceding 20 years of depression and war, very little had been built, inside or outside the village.

But with a baby boom underway and incomes surging, builders in the 1950s rushed to meet demand. The result was a countryfied version of suburban sprawl.

North of the village new housing subdivisions, with ranch and split-level houses, went up on farm fields where snow drifts used to pile up so high that schoolchildren missed a week or more of school. At the approaches to the village near Old Knowersville a grouping of new Cape Cod style houses, built primarily for GIs returning from World War II, sprouted up along Route 146 and the aptly named GI Road. Later, even John Armstrong’s cow pasture would be developed as the Armstrong Circle housing subdivision.

The automobile was now king. Businesses in need of parking and easy automobile access moved from the center of the village to the outskirts.

Portions of an orchard on lower Main Street were cut down and replaced with a gas station, an auto dealership, and the Thacher Drive subdivision. Part of Governor Marcy’s orchard near Schoharie Plank Road was replaced with auto service shops and a drive-in ice cream stand.

Victorian storefronts in the core of the village struggled while new car-friendly commercial buildings popped up on the previously open outskirts. The open space that ringed and defined Altamont was being gobbled up; the historic village was being turned inside out.

Fortunately, some key public uses — including the post office, bank, and school — were kept in the core of the village, even as they were redeveloped and enlarged. Later, several gas stations and auto shops on upper Main Street were converted to different commercial uses.

Collectively, these moves provided enough activity so that Altamont avoided the sad fate of so many historic business districts whose vitality was gutted by the demands of an auto-centered culture.

Protecting the village, inside and out.

Today, Altamont retains a significantly intact, and active historic core. It also still enjoys meaningful amounts of open and natural space surrounding the village.

It may no longer be a village in a garden, but visitors are still impressed with our historic, pretty little village nestled, as it is in such a beautiful natural setting.

These two elements — the historic built environment within the village and beautiful natural space surrounding it — are symbiotic. They work together to give Altamont its distinctive and valued sense of place. Remove one or the other and you remove that which makes Altamont special.

Great strides have been made in the last 20 years towards protecting the first part of the equation. Look around and you see that stores and restaurants, streetscapes, public buildings, and homes in the core of the village have been restored, renovated, and improved.

Business has revived and young families are finding Altamont to be a satisfying alternative to life in the suburbs. It’s been work but the results are apparent and rewarding.

But far less focus has been applied to the other necessary factor in the equation. Today the open spaces, fields, trees, and scenic views that are a major contributor to Altamont’s appeal are threatened as never before.

Threats to the landscape

Altamont retains a defining buffer of open space largely because the remaining open lands lie beyond the reach of existing public water and sewer infrastructure. But there has been talk of extending these lines and this has attracted the attention of out-of-town developers.

In fact, three of the largest open parcels between Guilderland Center and Altamont have been purchased in recent years by out-of-town home builders. There is a saying in the real estate development community that “smart money follows smart money.” It seems that the smart money is banking on public water soon connecting Altamont and Guilderland Center.

In the meantime, the subdivision of open space continues apace all around the village. The historic Crounse farm — some three-hundred acres where Altamont-Voorheesville Road connects with Brandle Road — has been in continuous cultivation for over 250 years.

Residents have long admired this farm for the iconic center hall Colonial home that backs up to the escarpment and for the acres of coneflowers and black-eyed susans that greet you as you approach the village on the Voorheesville Road.

Earlier generations valued these fields for supplying the wheat and other necessary provisions that sustained our Army at the Battle of Saratoga and as the place where the brave commander of our local Patriot Militia fought off a kidnapping attempt by Tories and their native allies.

Indeed, as you walk along these roads and fields today — with nothing but trees, crops, the escarpment, and a historic Colonial home in view — you can easily envision what life, and what our community was like 250 years ago at the founding of the Republic.

Future generations may know none of this. Their view may be limited to yet another cluster of modern McMansions on this historic site.

It’s not just residential projects that threaten Altamont’s open spaces. The last few years have seen a flurry of large, industrial-scale proposals including several projects to construct massive solar facilities in the countryside around the village.

Some of the more ill-considered projects have been defeated but, like the proverbial game of Whac-A-Mole, new projects continue to pop up, driven by financial incentives and rewards from the state.

As was true of the massive downstate transmission towers that first scarred our landscape a generation ago, state leaders today seem determined to address downstate’s energy demands by desecrating upstate’s beauty. There has even been talk of massive wind turbines crowning the top of the Helderberg escarpment.

The threat to historic, place-defining open space comes not just from large-scale projects. Collectively, a number of smaller, under-the-radar projects have the potential to fundamentally change the landscape.

A case in point is the recent residential and commercial subdivision and plan for a 16-acre open field across from Staucetts Nursery on Route 146. This site is the spot where our early Dutch and Palatine ancestors first settled; the Dutch speakers built their church near one end of the property, the German speakers built theirs on the other.

During the Revolution, the property was the farm and burial site of the Fetterly family whose family divisions mirrored those of our country at large: two brothers went to Canada to fight for the British while the father and another son fought for the Patriots at the Battle of the Normanskill and at Saratoga. The Patriot father is buried on the property.

In more recent years, this site was a Christmas tree farm. The trees that escaped the axe have since flourished into a beautiful mini forest of large balsam and spruce. The new owner — another out-of-town home builder — proposes cutting down the balsam grove and replacing it with a commercial self-storage and contractors’ equipment yard geared for roofers and contractors.

The community responds

Taken together, this barrage of large- and small-scale projects will fundamentally alter the character of Altamont as it has been known — and loved — by countless generations. Happily, the public is beginning to stir. People are increasingly coming to appreciate that land and development around Altamont plays a vital role in defining the look and feel of the village itself.

The town of Guilderland, which exerts land-use authority over all the land surrounding Altamont, is currently revising its comprehensive plan. Supervisor Peter Barber has gone on record as stating that the preservation of Altamont’s rural character and iconic viewsheds are key priorities going forward.

In the meantime, local citizens are taking initiative in response to the threat. One proactive effort is the move to create the Helderberg Greenway. The greenway is an initiative designed, in part, to establish a permanent buffer of protected, open or forested lands between the historic village and encroaching, suburban-style development.

The idea is to use conservation easements on private lands linked to parklands and similar quasi-public spaces to create a continuous belt of protected, public access land that will remain open or forested space.

The concept of the greenway represents a paradigm shift in land preservation: rather than constantly expending energy fighting a Whack-A-Mole series of recurring, misguided development proposals, residents can instead work to establish permanent protection for the land surrounding the village.

In time, the greenway will connect Thacher Park on the escarpment with the Hudson-Mohawk Land Conservancy’s extensive public preserves in the Bozen Kill Valley. Altamont’s two most important natural assets will be linked with a belt of open space, protecting historic and natural sites while buffering and protecting the historic village from the corrosive effects of sprawl.

As part of the vision for the greenway, Historic Altamont Inc. and the Altamont Fair have agreed to design educational hiking trails that will link to the village of Altamont’s Bozen Kill trails and the Museum in the Streets program as well as the extensive trail system at Thacher Park.

Significantly, this trail network will include an extension of the Long Path, the iconic 300-plus mile path that will soon link Altamont to Manhattan. In the future, when the goal to extend the popular Albany County Rail Trail to Thacher Park is taken up, the greenway will provide a vital link.

Greenway extensions are envisioned to link to the town's extensive Normans Kill Valley trail systems near Tawasentha Park. Likewise, the greenway can play a key role in realizing the long-held dream to once again allow visitors direct pedestrian access to Thacher and the Indian Ladder Trail from the valley floor in Altamont.

In time, Altamont can be the hub of one of the region’s most extensive — and beautiful — natural-preserve and public-trail systems.

But the greenway is not just about trails. A fully realized greenway will also integrate preserved agricultural lands, public forest preserves, summer camps, and similar educational facilities. The common thread is found in uses that preserve open and natural space and thereby preserve the natural setting that is such an important part of Altamont’s charm.

Economic growth that embraces the landscape rather than destroys it

Some mistakenly see strategic land conservation as being hostile to economic development. Done right, the opposite is true.

New commercial uses can and should make a major contribution to preserving Altamont’s charm. The idea is not to be hostile or discourage economic growth but rather to encourage and support those types of businesses — like Orchard Creek and Indian Ladder Farms — that build upon and integrate an appreciation of our unique Helderberg landscape into their core business offerings.

Tree nurseries, brew pubs, wineries, bike shops, and hiking outfitters are examples of commercial uses that increase economic activity while also increasing an appreciation of our landscape and natural assets.

However, continuing to allow single-family homes and incompatible commercial uses to fill in our open land is like eating the proverbial seed corn, destroying the unique assets that support many of our current businesses as well as our economic future.

Who wants to go to an agricultural fair in the middle of a suburb? Who dreams of an outdoor wedding in Westmere? Who can pick apples or tour a vineyard in Menands?

Each of those places have their economic strengths. For us, our strength and our draw are found in nature; the simple fact of the matter is that our unique landscape is both our natural heritage and our best economic future.

Where do we go from here?

For generations, Altamont has represented the proverbial end of the line, a destination of natural beauty and repose, convenient to but beyond the reach of urban crowding and suburban sprawl.

Its sublime setting and unique charms were recognized and valued long before Europeans set foot here. Humans as disparate as Mohican tribesmen and Victorian politicians recognized it as a special place, a place set apart, as it was for me as a boy in the 1960s.

But today we are at a proverbial crossroads. Can we remain worthy of our legacy as a “village in a garden” if most of the open space and vistas and beauty that constitute the garden are filled in and built over?

Will we continue to be that unique place set apart or will we wake to find all the open space gone as we inadvertently link ourselves in an unhappy chain of continuous, uninterrupted sprawl spanning all the way back to Route 20 and beyond? It’s a serious and timely question for all who love the place.

Editor’s note: Jeff Perlee represents Altamont, Guilderland Center, and part of the Hilltowns in the Albany County Legislature.