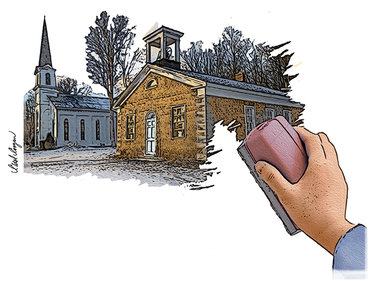

This historic schoolhouse still teaches

“History is the witness that testifies to the passing of time; it illumines reality, vitalizes memory, provides guidance in daily life, and brings us tidings of antiquity.”

— Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Oratore

Schools are often the center of their community — places that bring diverse elements of society together for a common cause: educating children, which is essential for a vibrant future.

The Cobblestone Schoolhouse in Guilderland Center served that function for decades — from 1860 when it was built until 1941 when it closed.

Last month, after a quarter-century of discussing what to do with the unused school, the Guilderland School Board voted to list the property for sale or auction. The school board’s Feb. 15 resolution says the schoolhouse property “is declared to be of no further use or value to the District and in fact, continued ownership of Property is fiscally detrimental to the District.”

We understand that the one-room schoolhouse is no longer needed by the district. Recent budget discussions make it clear the district needs to spend its funds on meeting the needs of current students. A fleet of buses now transports thousands of students in Guilderland to seven modern massive schools with all the latest amenities.

The schoolhouse, though, is worth preserving. It bears silent testimony to a bygone way of life, to a history that is easily erased. The building stands on land deeded to the district in the early part of the 19th Century by Stephen Van Rensselaer, the Dutch patroon, for the purpose of creating a schoolhouse.

Known as the “good patroon,” he was part of a long line of patroons perpetuating a feudal system of tenant farmers having to pay rent for the land they worked, leading to the Anti-Rent Wars in the Helderbergs. Going back to the earliest days of Europeans settling in what is now New York State, patroons would grant lands, rent-free, for churches and schools around which settlements grew.

Such grants shaped our topography.

In 1982, the Cobblestone Schoolhouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places along with a slew of other buildings in town — including the Helderberg Dutch Reformed Church just down the street from the schoolhouse, which has since burned.

The National Archives Catalog says that the schoolhouse “is one of only several cobblestone buildings in the county” and was “carefully maintained by the Guilderland School District since its construction in 1860.” The catalog goes on to describe the traditional 19th-Century construction technique as “exceptionally well executed.”

The catalog notes the building’s “smooth ashlar quoins,” the “stone lintels and sills,” and the “open bell tower … with curvilinear hipped roof.” In addition to picturing the schoolhouse, the catalog also pictures the privy in back, a structure that still stands. The schoolhouse has no indoor plumbing.

The Cobblestone Museum says of the schoolhouse, “Its solid foundations and walls remind one of a Revolutionary blockhouse.” The museum also notes that an inscription, carved on one of the upper front quoins, says, “R.E. Zeh, mason, 1860.”

That was first noted in a 1961 Altamont Enterprise column by Guilderland town historian Arthur B. Gregg, who wrote of the few rare cobblestone structures in town. Gregg wrote that cobblestone construction took place just from the 1820s until the Civil War era. Rochester is the center of the cobblestone region with few far-flung cobblestone buildings elsewhere.

Building with cobblestones was a laborious process, Gregg wrote, and it typically took to or three years to build a cobblestone house.

Since we wrote about the school board’s decision to sell the Cobblestone Schoolhouse, we’ve heard from many people who have fond memories of the place, and not just people whose relatives were educated there.

One of those people was developer Armand Quadrini. He was part of the group that, a half-century ago, worked to build the Guilderland Performing Arts Center at Tawasentha Park. The group met at the schoolhouse, and worked on repairing it.

“We put on a roof, reglazed all the windows, put in propane heat, patched the plaster, painted — all volunteers,” he said. Quandrini still has an oil painting of the schoolhouse that one of the group’s members painted for him.

We were heartened to hear Guilderland’s supervisor, Peter Barber, tell the town board last Tuesday that, after reading our story, he had written to the school superintendent, saying “We might be interested.” Barber emphasized the word “might,” adding, “We’ve got to do a lot of due diligence. Quite honestly, we’ve got to find out what will we use the building for.”

Barber asked Colin Gallup, the town’s park director who oversees its historic properties, to look at the schoolhouse. “He said there’s some problems with it but overall the building’s in pretty good shape,” Barber reported.

In 2017, the school district’s superintendent of buildings and grounds requested $30,000 to make needed repairs, at which several school board members balked. This brought many members of the public, town officials, and Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy to the board’s April 2017 meeting after which the board approved the repairs.

Floor joists and floorboards were replaced with fir appropriate to the age of the building and the roof soffit and fascias were replaced. The school had been reroofed in 2003 with era-appropriate cedar-shake shingles.

That same year, as Guilderland School Board members listed their priorities for the coming year, two of the nine members, who are no longer on the board — Catherine Barber, Peter Barber’s wife, and Allan Simpson — said that restoring the Cobblestone Schoolhouse was a priority.

Catherine Barber at the time described the schoolhouse, having peeked in through the window, as being frozen in time: There were the old-fashioned school desks and even maps on the wall as well as a pot-bellied stove, she said.

Peter Barber last Tuesday expressed similar enthusiasm to the town board and noted, too, that the property backs up to the town’s Keenholts Park. It could be “a bicycle and pedestrian connection for people directly in the hamlet to get to the park and not have to hop in a car,” he said.

Barber said he hoped the school district would turn the property — which is assessed at $167,000 — over to the town. “I can’t justify spending. I would just take it off their hands … take the responsibility,” said Barber, adding, “Once the town takes possession, that opens the door to a lot of grants ….”

Superintendent Marie Wiles told The Enterprise it is too soon in the process to know if the district would hand the property over to the town or put it up for sale. The decision would be made by the school board, which has not yet discussed it.

“It really is a gem … to have such a piece of history smack dab in the middle of a community,” Wiles said. “We as a school district don’t have the capacity to do it justice.”

That point is critical. If the town obtained the school, it would need to be sure it has the capacity to do the schoolhouse justice.

Unfortunately, on the same road as the schoolhouse, on the outskirts of Altamont, is a gaping hole where a historic structure once stood. The town together with the village purchased the Doctor Crounse House from Albany County in 2006 for $40,000 in back taxes.

Altamont’s first doctor, Frederick Crounse, built the house in 1833. He lived and practiced there for six decades. He also helped the Helderberg tenant farmers during the Anti-Rent Wars when they rebelled against the feudal patroon system. During the Civil War, the 134th regiment camped in front of the house, as Dr. Crounse stayed up all night, helping the regiment doctor with the sick and wounded.

The Guilderland supervisor at the time the purchase was made had thought the restored house would make a good center for youth activities. The Altamont mayor at the time had thought it would be a good site for a village museum.

When it was purchased in 2006, the condition of the house was deemed “fair to good.” As it languished — after a $25,000 grant secured by Assemblywoman Fahy to reroof the building was spent on something else — an engineer in 2017 deemed the primary structure “in generally good to poor shape.”

In 2018, Jay Cougar White Cloud, an internationally-known timberwright, backed by a newly formed grassroots group, Historic Altamont Inc., stepped forward to restore the house — without the municipalities having to pay him anything for labor or materials in exchange for him living on the 2.8-acre property.

The plan was for White Cloud to build a timber-frame structure for himself and to showcase traditional means of construction for the interested public. In August 2018, White Cloud was in the midst of covering the leaky roof with plastic, supported by Historic Altamont, when town officials stopped them. A month of heavy rains followed.

In the end, the municipalities spent more to demolish the historic building than they had paid to purchase it.

This cautionary tale is not meant to dampen enthusiasm for preserving the Cobblestone Schoolhouse. Rather, it is meant to inspire the town, or whoever ends up with the schoolhouse, to do it justice.

Over the years, we’ve covered many examples of historic structures, like the schoolhouse, that no longer serve their initial purpose being revitalized for a new community purpose.

When the passenger trains that built the village stopped coming to Altamont, the railroad station had no purpose. The village board at the time planned to tear it down but the station was saved by the vision and work of a committed group of citizens, spending money from their own pockets to buy it.

Many years later, the salvaged building was bought by the Altamont Free Library. Then many factions of the community — those who loved books, those who loved history, those who loved trains — came together to restore and refurbish the building that once again is the heart of the village.

In neighboring New Scotland, the mammoth century-old Hilton Barn no longer had a use since the farm it once served was being turned into an upscale housing development.

Some committed town board members dug in and worked to save it. The barn was moved across the street and, with the help of a land conservancy, a community foundation, and descendents of the barn’s original owner, land was secured to make a park.

Next to the county’s popular rail trail, the park is becoming an oasis amid houses that hearkens back to an earlier era, centered with an icon of agricultural heritage.

Old buildings, even if we have only a nodding acquaintance with them as we drive by on our modern highways, remind us where we came from and who we are. They distinguish our community from all the others. They give us a living link with history.

Keeping history alive informs and benefits us all. As Cicero wrote, it illumines our reality and provides guidance in our daily lives.

We hope the Cobblestone Schoolhouse survives to do just that.