Presidential election results reveal red shift across Albany County

Enterprise file photo — Michael Koff

Patricia Fahy, center, waits for Election Night results at the Italian American Community Center, where many Democratic candidates and their supporters had gathered. Like many Democrats in the area, Fahy won her election, but the presidential results that night showed that the Republican platform may have increasing appeal in the Democratic stronghold.

ALBANY COUNTY — When President Donald Trump pulled off his surprising victory in 2016, The Enterprise leaned on a Buffalo Springfield lyric to explain what then had been a shift toward the Republican party in the nominally Democratic Hilltowns: “There’s something happening here, but what it is ain’t exactly clear.”

Well, eight years later, Trump pulled off another victory, making gains with just about every major demographic group in the United States compared to his loss in 2020, along with most neighborhoods in the Enterprise coverage area.

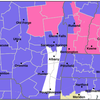

According to data compiled by the New York Times, Trump gained in almost every Enterprise region outlined in the Times map, which generally follows election district boundaries but not enough to be able to break it down as such. With that said, Trump gained in:

— Twenty out of 25 regions in Guilderland, (e.g. a 14-point gain in Parker’s Corners, a 6-point gain in the village of Altamont, and a 6.5-point gain in the Guilderland Center/Meadowdale area);

— Six out of seven regions in New Scotland (e.g. a 16-point gain in Feura Bush, a 15-point gain in Slingerlands, and an 8.9-point gain in a region just east of New Salem); and

— Just three regions across the Hilltowns, but none in Westerlo (e.g. a 12-point gain in the western half of Berne, a 6.5-point gain in the western half of Knox, and a 9.3 point gain across both regions of Westerlo).

If it wasn’t clear then, it’s clear now: The Republican platform — at least as it’s defined by the president — is increasingly viable in a county that’s been dominated by Democrats for decades.

Local outlook

“It was a big lift for the party,” Albany County GOP Chairman Jim McGaughan told The Enterprise this week. “We’ve seen more engagement, more donations, and obviously people are energized by taking back the presidency and both houses of Congress.”

Of course, the area is still hugely Democratic. Despite Trump’s gains, Kamala Harris still won most regions in New Scotland and Guilderland, and there were no Republican upsets in the few co-occurring local races.

“Things are changing, [but] it’s not a light-switch, right?” McGaughan said. “You can’t take a deep blue area and make it a red one overnight, but at the same time … I think we see a move towards the Republican Party.”

For one thing, he says that younger people are getting more involved with the party.

“I’ve talked with a lot of candidates in different towns, and I see a lot younger people stepping up, sending me emails, asking me about running, asking about joining committees,” McGaughan said. “I think, generally speaking, the Republican Party is getting younger for the first time in a long time. A lot of people have thought about the Republican Party as a kind of aging, older party, and that is changing.”

As you would expect, Democrats, on the other hand, are finding the post-election landscape a bit difficult to navigate.

Party chairman Jake Crawford told The Enterprise that recruitment has taken a hit because the “national political environment has made it tougher to convince people to run and serve in their communities because of the difficult climate in Washington, D.C. and across the country with how individuals view politics now.”

National influence

The big political — even sociological — question raised by the presidential results is to what extent local elections will be decided by national issues, and to what extent politicians should lean into or push against this factor.

Obviously, there’s at least a psychological impact, as suggested by Crawford. Even though the area is still extremely favorable toward Democrats, the effective disintegration of the national party, along with the increasingly polarized nature of political discussions, is discouraging to potential candidates.

And, while there’s no local data to verify voters’ national vs. local priorities, a preponderance of national concerns would follow a proven trend seen across the United States.

In his book “The Increasingly United States,” about the so-called nationalization of politics, political scientist Richard J. Hopkins notes that, in 2014, “the relationship between presidential and gubernatorial county-level voting was almost perfect, meaning that returns in governors’ races could be predicted quite accurately without knowing any state-specific information.”

A quick scan through Albany County’s election-night results show that state-level candidates generally performed within the ballpark of their presidential counterpart in each election district.

Despite this, both McGaughan and Crawford said that local campaigns are best served by talking about local issues — but there are suggestions that the Republican side is more willing to put local issues through a national lens.

Noting that he couldn’t speak for individual candidates’ approaches, Crawford said that he personally believes “it is always better to focus on the local issues that are impacting voters every single day. Those are the issues that local voters are most informed on and will have the largest change on their day-to-day lives. Local government needs to be responsive to their residents and those running for office should always be well informed on local issues over national issues.”

Meanwhile, McGaughan said, “I think, philosophically, it’s not that different, although the issues may differ. The philosophy of the Democratic Party is the same from national to local. Same thing with the Republicans. It’s generally the same from national to local, so I do think they’re tied in.”

The subtle difference in approach can be seen on each party’s Facebook page, where the Democrats post exclusively about local issues up to the county level, while the Republican page intersperses posts about local matters with more national ones.

“Every tax dollar sent to the government is a dollar not spent at a local business, a dollar not used for a startup, and a dollar that’s not invested to drive innovation,” a Republican post from March 2 reads. “These things are much more important than supporting DEI in Serbia.”

Republican Assemblyman Chris Tague, too, frequently invokes Trump in his posts.

It’s up for debate which approach is better for society, regardless of its political efficacy.

It’s a maxim in the U.S. — and one that gets repeated often after a national election — that local politics matters more than national to the average voter.

Hopkins notes that voters do actually believe this, despite being more engaged with national politics, bringing about what he terms the “presidential paradox.”

“This effect is especially pronounced when asking about the president as a person, suggesting that the overwhelming media attention on the US presidency might be one factor behind the disproportionate interest in national politics,” Hopkins said.

So, it can be easily argued — and is — that national motivations hurt local engagement by essentially reducing voters’ decisions about who to vote for locally to a handful of not-especially-relevant factors (like whether they support DEI in Serbia).

“It is no particular problem if voters do not split their tickets in national races — Democratic candidates for Senate are quite like Democratic candidates for the House of Representatives or for President,” writes David N. Schleicher in the Harvard Law Review. “But a failure to split tickets across levels of governments has a very different effect. Second-order state elections means that state government lacks meaningful accountability or representation … If elections simply produce either ‘red’ or ‘blue’ outcomes, there will be fewer choices for mobile residents, worse matching of preferences to policy, less representation of diverse cultures across states, and less policy experimentation.”

In terms of very local government — towns and the like — where there’s even less of an obvious connection between representatives at the two levels, it is certainly apt to model one’s civic duty on the assumption that local is where your influence is greater and outcomes more consequential, as this is physically, spatially true. This, after all, is the model of representation that the U.S. was founded on, with representative tiers flowing up out of local government divisions.

But that was a time when people were also experientially rooted to their actual location. It’s not a coincidence that nationalization, as Hopkins points out, accelerated during the 1960s, when televisions linked each person to a far greater number of locations and, therefore, expanded their consciousness of what was happening in the world, inevitably reducing one’s specific sense of place.

“In other realms of American life, nationalization is so apparent as to be indisputable,” Hopkins writes. “Consider retail. The United States has over thirty-five thousand cities and towns, and they vary tremendously in their size, geography, introduction and demographics. Yet, over the twentieth century, their storefronts came to look increasingly similar, as large chains like Walmart, Subway, and CVS replaced smaller, locally owned stores throughout the country.”

In the same way that products on shelves began to look the same in Kenosha, Wisconsin as they did in Fountain Valley, California, Hopkins says that political representatives also began to blend together as their images were being broadcast to an even larger group of people at one time than ever before.

This has only gotten more extreme as social media creates an infinite number of focal points with no regard for distance.

Although bad for one’s sense of place, some argue that this enhanced worldview is a benefit for local politics, which can suffer from an overly-concrete decision-making process, devoid of broader moral implications.

Consider the way millions of people watched the recording of George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota in 2020 while otherwise stuck at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the consequences this had on local police departments which, of course, had nothing to do with that particular incident.

If you can track voters’ engagement (their willingness to vote/attend meetings/etc.) and motivations (how they make their decisions) separately across the national and local domains, then, under the old model, a locally motivated and engaged voter would be considered better than a nationally motivated one.

This would be a voter who is more knowledgeable about local issues and makes decisions according to his or her interests, which, because they are not nationally motivated, is restricted to their narrow set of concerns (and perhaps those of any friendly neighbors).

There are issues — like renewable energy development — where this can become an obstacle.

Despite the fact that many homeowners are ideologically supportive of renewable energy, many wind up opposing solar and wind facilities because of the impact it would have on their living space — dissociated from the near-unanimously-accepted consequences of climate change.

It’s to this point that Noah Kazis, also writing in the Harvard Law Review, argues for the benefits of nationalization.

“In New York City, many immigrant families live in illegally converted basements or cellars,” Kazis writes. “With less access to public and subsidized housing, immigrants have been forced to turn to crowding and subdividing property instead. As John Mangin has described, an estimated three-quarters of all housing growth in the borough of Queens has come from illegal conversions, with the tactic particularly common in that borough’s Bangladeshi, Indian, and Indo-Guyanese communities.

“Accordingly, advocates for these communities have long pushed to legalize, or otherwise support, this ‘housing underground,’” he continues. “Local politics, however, were not kind to these efforts. Politicians — many less-than-responsive to a non-voting, non-citizen population — saw basement units as a nuisance, not a desperately needed source of housing for a vulnerable population.

“This was a classic local question, involving land use and building codes and conflicts between new residents and incumbent homeowners. And for years, it had a classic local resolution, with those same, well-established homeowners deciding the outcome.”

But when Trump took office and progressives became more urgently concerned with the effects his administration would have on immigrant communities, there was a renewed, much more ideologically rooted push for ways to help them, Kazis says.

“Here, the nationalization of local politics didn’t divert local government from its core duties,” he writes. “Rather, it reinvigorated local government in its pursuit of those duties. Basement apartments shifted from being seen primarily at the neighborhood scale as a quality-of-life concern about overcrowded schools and scarce parking to being seen through a national lens as a piece of the pro-immigrant agenda.

“The old, purely local concerns didn’t disappear (and conversely, it would be incorrect to give all the credit to immigration advocates), but a different, more ideological perspective was elevated in the conversation.”

Conclusion

Who knows what all this means for the political parties in Albany County. Perhaps the vestiges of the Democratic political machine will stick around and the party will thrive; maybe not.

As The Enterprise noted in 2016, “There’s something happening here, but what it is ain’t exactly clear.”

The only thing for certain is that the world within and beyond Albany County is changing, and everyone has to find a new way to think about and exist in it.

With that in mind, it may be worth amending that original lyric, from the reformative 1960s, with a new one from a Vampire Weekend song that was released in 2024, just months before old ways of being were again called into question, and many felt they’d been sent adrift.

“They always ask me about Pravda, it’s just the Russian word for truth / Your consciousness is not my problem, because when I come home it won’t be home to you.”