Affordable senior housing critical for communities, but so is outside funding

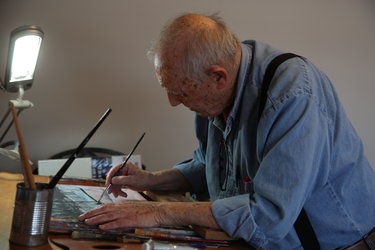

The Enterprise — Michael Koff

John R. Williams, 91, paints in the art room at the Summit at Mill Hill on Tuesday. He and his wife, Marlene, moved to the Guilderland complex three years ago after selling their home in Knox, which has no senior facilities. Williams’s artwork is currently on display at the Mill Hill gallery.

GUILDERLAND — With the senior population in the United States and Albany County on the rise, communities are facing an increased need for housing that accommodates the unique needs of this demographic while remaining economically accessible.

But building large-scale facilities, even in relatively large towns like Guilderland, where several already exist but more are needed, is no easy task, facing the same frictions that any new development will face on top of the fact that affordable housing is, by nature, not especially profitable for developers.

This week, as Guilderland holds its first public hearing on updates to the town’s comprehensive plan, Town Planner Kennth Kovalchik laid out for The Enterprise the difficulties that such projects face.

Challenges include the state’s complicated environmental review process — which, while important for avoiding environmental hazards, opens projects up to legal challenges that can delay or stop them entirely; the costliness of meeting certain state standards; and a lack of state funding that allows projects to meet these standards and operate as sustainable businesses once they’re built.

However substantial the challenges are, though, they must be overcome to meet the housing demands coming down the pike.

Boomers and their needs

According to the Capital District Regional Planning Commission, the senior population— those 65 and older — will peak in the Capital Region around 2030, when that group is projected to make up more than 20 percent of the overall population.

That’s up from about 18 percent as of 2020, and 14.4 percent in 2000. The share will stay relatively stable through at least 2050, according to CDPRC data, which ends there.

The share of residents who are in the oldest category — 85 and up — will increase as well, from 3 percent in 2030 to 5.3 percent in 2050, even as the total senior share begins to recede slightly.

Kovalchik acknowledged these shifts using national census data, where the numbers can be even more stark.

“The year 2030 marks a demographic turning point for the United States. Beginning that year, all baby boomers will be older than 65,” he said. “Between 2016 and 2060, the population under age 18 is projected to grow by only 6.5 million people, compared with a growth of 45.4 million for the population 65 years and over.

“Aging boomers and rising life expectancy will increase the older population as well,” he went on. “The population 85 years and older is expected to grow nearly 200 percent by 2060, from 6 million to 19 million people. The number of Americans ages 100 and older is projected to more than quadruple over the next three decades, from an estimated 101,000 in 2024 to about 422,000 in 2054.”

With these figures, it’s not surprising that the senior-housing market is on the precipice of a boom period, even as it reels from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the industry publication Senior Housing News, using data from the American Seniors Housing Association, nearly 70 percent of baby boomers who responded to a survey said that they would include senior housing in their list of options when looking for their next home, with a third of these saying they would stay within 40 miles of their current home.

While nearly all of them — 92 percent — placed a high value on independence and self-sufficiency, less than a quarter said they “preferred to live within their own home.”

This means that part of the growth of the senior housing market is expected to include “active adult” properties, which strive to provide a higher quality-of-life at the expense of services typically associated with contemporary senior facilities.

The National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care suggests that those looking to develop active-adult facilities avoid using the word seniors, and don’t provide transportation or meal services, instead focusing on “edgy,” community-oriented spaces, like bars, and ensuring that the locations are near restaurants and other amenities.

Industry-watchers have also noted a shift of these types of locations from the Sun Belt to the Northeast, as residents apparently have been placing proximity to family over warmer weather, according to an analysis by 55Places, a real-estate site.

However, these projects — like Guilderland’s controversial Hamilton Parc — are relatively high-cost and therefore accessible mainly to wealthier boomers, who are also expected to be generally healthier and therefore less reliant on care services.

The National Improvement Center notes that proper housing may be more difficult for the “forgotten middle” of the boomer demographic, whose incomes range between the 41st and 80th percentiles, meaning they don’t qualify for low-income benefits, nor can they independently afford the high costs of senior living as easily.

The center highlights this demographic as an untapped market requiring innovative housing options from developers.

Senior housing in Guilderland

Guilderland — with a population of nearly 37,000 over a quarter of which are older than 60 — already has a good number of senior housing facilities, both older and more recent, that serve the town’s housing needs.

They, according to Kovalchik, are:

— Mill Hill Development, on Route 155, which includes the Peregrine Assisted Living Facility and Summit at Mill Hill senior apartments;

— Serafini Village, on Western Ave, a 104-unit development with 35 units rented to Section 8 tenants, with more demand that’s not able to be satisfied due to the limited number of Section 8 vouchers currently held by Guilderland;

— Carman Senior Living Facility, on Carman Road, which has 96 units;

— Promenade at University Place, on Western Avenue, a former hotel that was converted into a 200-bed assisted-living facility, where 40 percent of the units are available for income-restricted residents who meet the medical-needs requirements;

— Westmere Village Senior Living Facility, on Riitano Lane, which is two three-story buildings with 36 units each;

— West Old State Road Senior Living Facility located on the road of the same name, which currently has three, four-unit buildings with a new proposal submitted for another three, four-unit buildings;

— 3407 Carman Road Senior Living Facility, a proposal designated after its location, which just recently obtained site-plan approval for a 12-unit senior living facility; and

— Hamilton Parc, on Route 155, which just opened its first 140 units last year out of the 256 that were approved and, as mentioned, accommodates the “active adult” demographic.

Kovalchik also said that there are 53 taxable accessory-dwelling units in the town; ADUs are relatively small housing units built on the same property as a traditional home, and are often used to house older residents.

The rural town of Westerlo has been working to make ADUs easier to build in the town as a fallback given the lack of local senior housing there, something that Kovalchik said he applauds.

“Allowing ADUs is just one of many measures local governments can take to address housing affordability,” he said.

He went on to recommend that Guilderland follow suit by allowing ADUs to be built as detached units, as well as getting rid of the requirement that they only be inhabited by relatives of the property owner, which Kovalchik said could address housing affordability for younger people as well by increasing the number of rental units in the town.

Challenges

With regard to large-scale senior housing, and housing in general, Kovalchik said there are several obstacles in place.

“The land use review process and State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) requirements in New York State is a highly regulated area,” he said. “If a lead agency makes a mistake during the SEQRA review process, does not conduct a hard look at the proposed development, and is challenged via an Article 78, the land use approval and/or SEQRA negative declaration adopted by the lead agency could be overturned by the NYS Supreme Court.”

He also said there were a number of local examples of state requirements being too costly for developers, tanking their proposals.

Kovalchik pointed to the Foundry Square Planned Unit Development — a proposal for two, four-story buildings that contain a total of 260 apartments — as a project that would be required to spend up to $1.5 million on intersection improvements, with no support from the state’s Department of Transportation.

“A previous missed opportunity to construct multi-family housing, due to financially burdensome offsite improvements, include the previously proposed Winding Brook Commons PUD at Western Avenue/Winding Brook Drive, which proposed 200 multi-family units and 20,000 square feet of commercial space,” he said.

“As an involved agency in the PUD review the NYSDOT provided multiple review comments associated with the proposed development,” Kovalchik said of the state’s Department of Transportation. “The NYSDOT required significant improvements to the Winding Brook Drive/Route 20 intersection and the installation of an approximate 2,000-foot median extending from this intersection to the east as a means to improve vehicular safety and better control the flow of vehicles in this corridor,” he said.

“The developer found that NYSDOT required roadway improvements were not financially viable for the project and did not proceed with obtaining PUD approval,” he concluded.

Kovalchik suggested that the state be more involved in the funding of housing projects so that these obstacles are more surmountable.

He cited the previously proposed Pine Bush Senior Living Community, which got town board approval in 2017, but twice failed to obtain a state low-income housing grant, despite a report that demonstrated a clear need in the area.

The project would have included a 56-unit assisted-living facility, a 40-unit memory-care facility, and, after an amendment, an 86-unit independent-living facility for mixed-income seniors.

An independent report had “concluded there has been ongoing new market rate development in Guilderland and no new affordable housing of any kind added in the market in recent years,” Kovalchik said. “There is clear demand in the area based on the low capture rate and the high number of income-qualified households not living in affordable tax credit housing that would support the project.”

Ultimately, the approval for the project expired, as it had been reliant on state funding.

“Another example is in 2019 the Beacon Meadows Special Use Permit was approved by the Zoning Board of Appeals for a 65-unit development consisting of 52 age restricted units (55+), 5 units for foster, adoptive or kinship care families and 8 units for young adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities,” Kovalchik said.

Like the Pine Bush project, the developers were twice denied state funding and the town’s approval has expired.

There is also, of course, community pushback.

Hamilton Parc was extremely controversial due to the relatively high cost of the apartments, which residents have argued are above market rates.

“In my opinion, when you factor in the value of the services and amenities offered onsite as part of the rent the monthly rates are competitive and reasonable when compared to other rents in the area,” Kovalchik said, giving the pool, sauna, gym, movie theater, library, and golf simulator as examples.

Opposition was strong enough that an Article 78 was filed against the town for improper review, though the judge ultimately found that the town’s zoning board of appeals had done its due diligence and “conducted a hard look of the application and its potential impacts, and mitigated impacts to the maximum extent practicable,” Kovalchik said.

Solutions

Kovalchik said he’s hopeful that the town’s new designation as a “pro-housing community” will make it easier for applicants to get state funding for affordable housing.

“Many of the steps the Town Board endeavored to take when adopting the Pro-Housing Communities Pledge included adopting policies that affirmatively further fair housing, incorporating regional housing needs into planning decisions, increasing development capacity for residential uses and enacting policies that encourage a broad range of housing development, including multifamily housing, affordable housing, accessible housing, accessory dwelling units and supportive housing,” he said.

“I’m also hopeful that an outcome of the current Comprehensive Plan Update will include updates to the Town Code that further these housing initiatives,” he said.

Ultimately, he said that the senior housing problem should be solved with an “all-of-the above” approach, that uses a mix of large- and smaller-scale facilities offering a diversity of services and amenities for different kinds of groups.

“Continuing to provide this diversity of senior housing options for the senior community is appropriate,” Kovalchik said. “There has also been a diverse range of independent living and assisted living facilities constructed in Town. The Mill Hill development is a good example of a community that offers senior townhouse style and apartment options and assisted living all within the same development, and the ability to age in place within the same development.”