Is an historic blockhouse hidden in plain sight?

GUILDERLAND — Winslow, Maine has long been considered the site of the oldest standing blockhouse in the United States.

A National Historic Landmark, it was part of Fort Halifax, built by English settlers in 1755 to defend the Kennebec River Valley from attack by the French and their Native American allies.

But Mark O’Brien and John McCormick believe that they have found an older blockhouse, built before 1746, still standing in Guilderland.

They found it hiding in plain sight — on town-owned property.

The pair have been friends since boyhood. They frequently played together along the banks of the Blockhouse Creek.

“We frolicked in the woods,” recalled McCormick.

“We built forts,” said O’Brien.

One day, their history teacher at Farnsworth Middle School, John Farley, heard O’Brien say he crossed the Blockhouse Creek on his way to school.

“He asked where the blockhouse is,” recalled O’Brien, a question that has haunted him for half a century.

Both men, each in their mid-sixties, are now retired. This past summer, they decided to answer their history teacher’s question from long ago.

“We’re like the Hardy boys,” said McCormick, referencing the teenage sleuths from 20th Century childhood books who solved mysteries that eluded adults.

O’Brien has spent countless hours researching historic maps, newspapers, and archeological records.

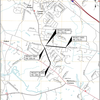

Using both antique maps and a map that O’Brien drew himself of Guilderland in the mid-18th-Century, they took to the woods and their childhood haunts, carefully combing the Blockhouse Creek and its environs.

O’Brien runs a Facebook group, steeped in nostalgia from his Westmere childhood. “Everyone was following along,” he said, as he cataloged their explorations. “I stopped because I didn’t want people with metal detectors to come and destroy archeological evidence.”

One of the things they found was an experimental wheel from the 1800s invented by Joel Benedict Nott to help the mill run more efficiently. O’Brien looked up Nott’s 1852 patent for the “water wheel,” complete with a sketch.

Nott, he learned, was a professor at Union College, the son of Eliphalet Nott, the college’s president. O’Brien, with his tenacity in researching history, followed the many tentacles of Nott’s life, making links to other historical figures.

O’Brien, a poet, is someone who, when he looks over a Guilderland landscape, can tell you the layers of who lived where in what time period.

He says history is in his DNA: His mother was a founding member of the Guilderland Historical Society and his father read the manuscript for James Crowley’s “The Old Albany County and the American Revolution” before it was published.

McCormick, who had a career managing refrigeration and air-conditioning for the University at Albany, is someone who can look at Nott’s invention, and explain how it works. He is also someone who, in their summer explorations, walked across a log crossing the stream holding a pole to balance himself like a circus tightrope walker; O’Brien took a picture to prove it.

This week, on a cold rainy morning, the pair reenacted their discovery for The Enterprise.

They stood on Mill Hill at the top of what the Schenectady Patent calls the “Normans kil road.”

Native people used this route, O’Brien explains, to portage from the Mohawk River to the Normanskill.

He displays on his cell phone an 1851 map that shows the road. To the uninformed viewer, the path through the woods looks like just a cut for utility lines.

The Mill Hill property in the mid-18th Century was part of the Van Rensselaer patroonship, leased by the Veeder family

O’Brien had found several historic references to a blockhouse in the area. The seminal one was a “Extract of a Letter from Albany, dated May 24, 1746,” and published that year in the Boston Evening-Post on June 9.

The unsigned letter was written in the midst of the third of the four French and Indian Wars. Often called King George’s War, it raged from 1744 to 1748.

The 1746 letter from Albany begins, “We are in such continual alarms, that I have not had no time to write you sooner, and could rejoice could I now write on a better subject, but all around us is nothing but desolation, fire, murder, and captivity.”

The letter goes on to describe local skirmishes including this one, in what is now the town of Guilderland:

“We hear from Norman’s Creek, about 8 Miles to the Westward of the City of Albany, that fourteen men all armed, went with a Wagon to fetch some Corn from one of the Farms they had deserted, in order to bring it to the House where several Families had removed to for their Safety, were met by a Party of Indians who killed and took twelve of them Prisoner, the other two made their Escape and are got to the City; one of them is wounded in the Shoulder: we have not yet Heard the Names of those unfortunate People; tho’ as we know what Families lived there, we may guess who they are. The Affair is told with such circumstances, as makes us believe the news to be too true.”

In “A History of the Schenectady Patent in Dutch and English Times,” O’Brien had read, “It was improbable that any man with a military eye would locate a blockhouse back from the steep bluff bank of mill creek — it would be placed on the crest so that the guns of the blockhouse could fully command the whole slope.”

Mill Hill was on a bluff above the Normanskill but it was missing a road. That’s when O’Brien started looking at old maps.

That day last summer, as he and McCormick emerged from their exploration along the old Normans kil Road, they saw what is colloquially called the Ballet Barn straight ahead. Jane DeRook, O’Brien’s doctor when he was a boy, had founded the Guilderland Ballet, which had held classes in the town-owned barn.

As a young man, O’Brien had attended church at Mill Hill. It was the home to the Mill Hill fathers, an order that started in Mill Hill in London, O’Brien said, adding that, in that era, the barn was used as a dormitory.

As McCormick and O’Brien, after exploring Veeder’s Mill and its dam, walked back up the old road, they thought the blockhouse must have stood where the barn is now.

As they walked around the building, lamenting its neglect, they saw a section on the back side that was exposed when an attached water pump shed was removed.

That was their eureka moment.

Fieldstone was packed between the studs, a defense against musket balls or stone-tipped arrows, they surmised.

O’Brien crept into a hole under the foundation. There he saw a wooden coopered barrel filled with cement to form a pier to support the structure, similar to today’s sonotube.

McCormick had learned that the kind of saw used in the mid-1700s was a sash-blade, which made up-and-down marks at half-inch intervals. Those distinctive saw marks were on the beams supporting the barn.

O’Brien, through copious research, has since pieced together what he believes happened on that day in 1746. He is writing about it in a book he hopes to publish on the history of the blockhouse.

“On a mild early morning in May 1746,” begins his chapter on the raid at the Veeder family blockhouse, “a band of French and Nepissing Indians from the province of Ontario led by Chief Ontassago left on a raiding mission.

“It was the height of King George’s War in the colonies. The French and Indian forces out of Fort Saint Frédéric on Lake Champlain had been waging a successful campaign of terror against the English colonists in New York from this location since the beginning of the war.”

O’Brien believes that the Nepissing camped on what is now the front lawn of the Normans Vale House, built in 1780, and foraged raw Normanskill chert at the fording place, now used as a rifle range, to create new spear and arrow points.

“Upon breaking camp in the morning,” O’Brien writes, “the band of Nepissing Indians headed out towards the Normanskill and the Veeder Homestead ….”

“This has been bottled up inside me for months,” said O’Brien, telling The Enterprise he is glad the word will be out.

“It’s been here all along, right in front of everybody,” he said of the barn that may contain the original historic blockhouse.

“Mr. Farley, we found it,” he said.

I remember Mr. Farley but pre the middle school being built!