Redux: TJA Energy proposes 4.25 megawatt solar facility in Berne

BERNE — After tabling a project in 2020 because of a then-recently adopted local solar law, TJA Energy is back in Berne with a proposal for a 4.25 megawatt solar facility at 57 Canaday Hill Road.

This time, the company benefits from a solar law that the GOP-backed town board adopted in 2022, that overrode the earlier law, passed in 2019 when Democrats still had control of the board.

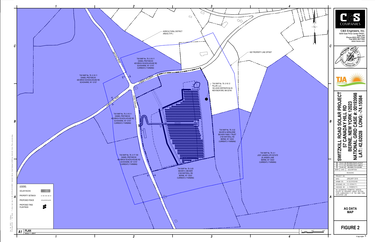

While that earlier law had restricted projects to 10 acres, the current law upped that threshold to 30 acres. TJA’s proposal says the area of disturbed land would be a little more than 20 acres on a roughly 46-acre property owned by an LLC that shares an address with the developer and is managed by a man named Antonio Alves.

However, the solar panels themselves would only cover around 4.6 acres, according to the company’s application documents, which can be found on Berne’s homepage.

The property is in a Residence, Agriculture, and Forestry zone.

While the solar law’s size requirements are not a problem for TJA, the company is seeking a variance on the setback requirements, since the project would be 16 feet from the property of Jay Becker, while the law requires at least a 200-foot setback.

A letter written by Becker included with the application documents states that he and his family have “no objection to the proposed location” following a discussion with TJA’s president, Michael Frateschi, where they reached an agreement that the Beckers could lease the remaining area of the property for farming for the life of the solar project, which is expected to be at least 30 years.

According to the agricultural data statement in the application, the property has prime soil.

Through its attorney, E. Hyde Clark, TJA argued in a letter to the zoning board of appeals that the variance should be allowed because the project meets the public utility variance standard established by the New York State Court of Appeals, the state’s top court, which holds that “compelling reasons” allow “a company that provides an ‘essential service’” to only demonstrate those specific reasons to receive a variance.

Clark claims that solar energy projects are necessary because they generate electricity and align with state and federal climate goals. The compelling reasons are, according to Clark, that there’s no alternative site available for this project — due to the various requirements a property has to meet, including proximity to utility lines — and that meeting the setback requirements at the current site would have a greater environmental impact.

A visual analysis included in the application suggests that the project, at a maximum of 12 feet off the ground, would be largely invisible from most vantage points, with exceptions along Switzkill and Sickle Hill roads, and a separate analysis claims there’d be no glare.

The environmental assessment says that construction would be over a period of eight months, which, according to an acoustic analysis, would be the noisiest the property gets, after which the noise level at the nearest property line would be 47.3 decibels — a bit louder than a suburban area at night, and quieter than a household refrigerator, according to a Yale University chart.

Up close, the property’s converters and transformer would reach a noise level of 76.7 decibels, according to the analysis. That’s slightly louder than a vacuum, per Yale’s chart.

The application also includes a 476-page stormwater pollution prevention plan.

Long road ahead

Solar facility proposals are almost always controversial in the Hilltowns, where many residents are concerned about preserving rural character. In Berne, there’s the added fuel of long-standing political tensions.

Then-town board member Joel Willsey, a Democrat who had voted in favor of the 2019 solar law, framed the board’s replacement of that law in a 2021 letter to the Enterprise editor as one of several “symptoms” of an administration fighting against the preferences of residents as captured in the town’s comprehensive plan.

Earlier in 2021, he had written a letter to his colleagues on the board arguing against the law. In 2020, the planning board advised the town against adopting the law as it was then drafted, with lower setback requirements than are in the current law.

The planning board had also argued that year that the town board was denying the planning board its obligation to review laws that impact land use, leading to a bitter spat between town attorney Javid Afzali and Larry Zimmerman, then a member of the planning board.

In accordance with Berne’s solar law, the project’s fate will be determined by the zoning board, which is headed by Tom Spargo, the county’s Conservative Party chairman and a former state Supreme Court justice who was disbarred after a conviction on bribery charges.

Frateschi told The Enterprise this week that the facility is smaller than what TJA was going to propose in the past, in terms of both overall footprint and the area taken up by panels, and that TJA “also incorporated a few more agricultural elements including sheep grazing and bee apiaries.”

The 2020 iteration of the project was expected to generate enough electricity to power 1,000 homes, Frateschi had said at the time, calling it a “community solar farm.”

Frateschi could not immediately be reached by The Enterprise to answer whether this project is the same as the project the company was getting ready to propose in 2020, but he told The Enterprise that year that the 2020 iteration of the project would generate enough electricity to power 1,000 homes, calling it a “community solar farm.”

Except in certain instances, homeowners don’t get electricity from specific facilities nearby; rather, the electricity is gathered by utility companies, and customers subscribe to a renewable energy service, such as Nexamp, which generates credits for those customers. This is available to customers regardless of their proximity to a facility.

In 2020, the project would have been overseen by the town’s planning board — which then, too, was headed by Spargo after the board had appointed him in what turned out to be an illegal maneuver.

He was first appointed as chairman of the zoning board in January of 2022, a few months before the town board adopted the updated solar law.

Spargo could not be reached as an Enterprise email to his town address was repeatedly kicked back with the message that “the recipient's email provider rejected it.”

Frateschi told The Enterprise this week that the company was “not directly communicating with the Town” as it updated the solar law “but followed the process as they wrote a new bylaw.”

Dawn Jordan, a former town board member who had voted in favor of the 2019 solar law, told The Enterprise that the current law does not reflect the will of the residents.

“At the public hearing for the updates to the 2019 solar law, every single person attending who spoke, spoke against it. This included at least one Westerlo town official, based on the negative experiences they had with their facility. Everyone’s words went unheeded.”

That Westerlo official, Supervisor Matt Kryzak, has spoken with The Enterprise before about how the negative impacts of solar outweighed the money the town brought in through payment-in-lieu-of-taxes, or PILOT, agreements.

“Progress for the sake of progress doesn’t get you anywhere,” Kryzak said in 2022. “I think we found out firsthand that we thought we were doing all of these wonderful things, but when everything was said and done, the budget needle didn’t move that much.

“The townspeople aren’t very happy about it. The most scenic parts of town have been turned into an industrial complex. So there’s a balance, and each town needs to find out, depending on the residents’ opinions, what their financial needs are.”

Jordan also highlighted this week that the town will receive less money from the developer at the outset than it would have under the 2019 law.

She said the 2019 law had a “fee structure based on the size of the facility that would offset the legal and zoning office work that will be required by the town for the installation of the facility, plus an annual fee that would benefit the town taxpayers for the life of the facility.”

The current law charges a $1,000 application fee, “plus $100 per disturbed acres for the first 10 acres, then $250 per disturbed acre for acres 11 through 20, then $500 per disturbed acres 21 through 30 shall be required as an initial application,” according to the law itself.

“This,” Jordan said, “is a much less transparent calculation – what exactly is included in ‘acreage disturbed?’ And the residents have no way of verifying the accuracy. I don’t know what the acreage calculation will work out to, but under the 2019 law the town would have received an initial special use permit fee of $42,500 for a 4.25mW facility, and an annual fee of $34,000 for the life of the facility in addition to a PILOT agreement or tax fee.

“Given the jump in property taxes this year and very likely next year, and the fact that we won’t be receiving the annual state rebate we’ve been getting lately when a town keeps their tax increase below 2%, it seems like the taxpayers would have appreciated the 2019 law’s fees.”