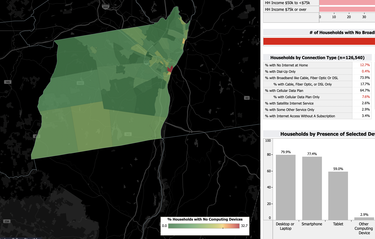

State broadband map shows tech and internet gap on the Hill

ALBANY COUNTY — For the first time, New York State has compiled municipality-level data on internet connectivity and presented it publicly in the form of a map, which confirms in numbers what many have already known through anecdote: the rural Hilltowns are behind both on internet and technology as are parts of the cities of Albany, Cohoes, and Watervliet.

According to the map, which was generated by the New York State Education Department, the New York State Library, Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Community Tech NY, and the John R. Oishei Foundation, approximately 15 percent of the Hilltowns’ 4,264 households are without internet for one reason or another, whether it be lack of an internet subscription or lack of devices that are internet-capable.

About the same proportion of children under the age of 18 are without internet, the majority of whom lack broadband rather than devices.

The map also shows that income is a major predictor of connectivity, as the connection rate for each household-income category above $35,000 per year in annual income is higher than 80 percent while the rate for the $20,000-to-$35,000 category is 69.4 percent, and the rate for the $10,000-to-$20,000 category is 35.3 percent. However, for households with incomes below $10,000 annually, 66.4 percent have broadband.

About 13 percent of households in Albany County overall lack home-internet. Guilderland and New Scotland, both of which are in the Enterprise’s coverage area, each have connection rates of around 90 percent.

Among the Hilltowns, Rensselaerville is in the worst shape, with 9 percent of its total population lacking a computer at home and 16 percent lacking internet connection despite having a computer. Berne is next, with around 9 percent of its population without a computer and 10 percent without internet. In Westerlo, nine percent of residents don’t have a computer while 5 percent have no internet. In Knox, 2 percent of residents have no computer and more than 7 percent have no internet.

The data for this map comes from the United States Census Bureau, making it highly likely that the internet problem in the Hilltowns isn’t adequately captured, since many residents who technically have both a web-device and an internet connection suffer from slow speeds that make it difficult to take advantage of either of those things.

Last year, Westerlo adopted a new comprehensive plan that stated 61 percent of survey respondents either didn’t have internet access at home or were unhappy with their speeds. Berne-Knox-Westerlo Superintendent Timothy Mundell announced in 2020 that 30 percent of Berne-Knox-Westerlo’s student body had inadequate internet.

Westerlo applied (and is still in the running) for a $1.7 million broadband grant through Congressman Paul Tonko’s office, hoping to use that federal money to cover the high cost of installing cables throughout the town, something internet service providers won’t do themselves because the low population density means a poor return on investment.

Because the low population density and the difficult terrain of the Hilltowns mean lower broadband availability, many households rely instead on satellite internet connections. According to the digital equity map, a little more than 14 percent of households use satellite, compared to less than 3 percent of households countywide.

One federal initiative invested $885 million in Elon Musk’s company SpaceX so that it could expand its own satellite internet service across the country, including to the Hilltowns, as part of a larger effort to incentivize internet service providers to close the connectivity gap.

It’s ambitious, money-pumping solutions like that and Westerlo’s grant application that Hudson Valley Wireless General Manager Jason Guzzo told The Enterprise two years ago would be key to solving the internet problem for rural communities.

But, he said, part of the problem securing federal funding is that connectivity is tracked at the census-block level, and census blocks — particularly in rural areas — can be large and irregularly shaped. As long as one household in a block has an internet connection, the whole block is considered served, and those areas are overlooked in favor of ones that are more obviously disconnected.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of the internet in daily residential and work life, and in municipal reach. When local government meetings moved to a digital space, there was much concern in the Hilltowns about looping in residents who aren’t able to connect.

And it’s a self-perpetuating problem, since the only way to properly assess an area’s connectivity rate is to do so through surveys, like the one employed by the Westerlo Comprehensive Plan Committee, which are expensive when they must be conducted through non-digital means. Furthermore, Westerlo’s survey, which had to be filled out by hand and mailed back or dropped off, only had a response rate of 30 percent, representing 455 out of approximately 1,500 households in the town.

Although the state’s digital equity map is likely understating the severity of the internet issue on the Hill, it at least acts as a stepping stone for small towns that otherwise would have enormous difficulty even outlining the problem, let alone beginning to take the big steps necessary to solve it.