I disapprove of your refusal to get the COVID vaccine, but I will defend to the death your right to refuse it. Specifically, your death. I will defend to your death your right to die.

But you have to meet me halfway. Because if you’re going to decline the vaccine, you can’t then be a sniveling crybaby who runs to the emergency room when your infection gets out of hand. No. Stand tall and proud — or, more realistically, lie shivering in a fetal position — and demonstrate the courage of your conviction by riding out the illness at home.

You’ll be OK. After all, I survived COVID before there was a vaccine, and you’re probably also in your thirties and in the best shape of your life. So you’re good.

But, if your luck does run out, have some dignity; don’t be posting TikToks or Snaps or Tweets imploring others not to make your same mistake. I’ve seen hundreds of those videos, and, frankly, the production quality is lacking. That said, if you feel irrepressibly compelled to film yourself gasping for air as you mournfully lament rejecting the vaccine, please at least do it over a sick techno beat.

Whatever you do, stay bedridden in your apartment, like the American hero you are.

To be clear, I’m not saying the unvaccinated shouldn’t go to the hospital for other afflictions. Like, if you don’t have COVID and you break your arm, by all means book a room at Albany Med. (Assuming, of course, that hospital beds are still available. You’ll want to beat the rush, since your unvaccinated compatriots are 29 times more likely than their vaccinated counterparts to be hospitalized with an avoidable COVID infection.)

What I’m saying is that, if you’re unvaccinated and you get COVID, stay home and shut up. Shutting up will help you avoid wasting the oxygen you’ll so desperately need while struggling to respire.

Let’s review:

Vaccinated? Go to the hospital.

Unvaccinated and COVID-negative? Go to the hospital.

Unvaccinated and infected by COVID? Snuggle up with some saltines and a ginger ale so you can binge-watch Netflix until you either beat the virus or die.

No matter what, don’t call 9-1-1. You’re better than that. Be a man and commit to your decision. You made your bed, now lie in it, as your night sweats drench the sheets and you lose the ability to smell the putrid stench of decay. Your blood oxygen level may plummet, but maintain your resolve; through the haze of fevered dreams, remember that you knew better than presidents Biden, Trump, Obama, Bush, Clinton, and Carter, all of whom implored you to get vaccinated.

Remember that you knew better than 96 percent of accredited medical doctors, to include your own. You knew better than the United States military, insurance companies, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and God.

That’s right, even God is urging you to get jabbed. He hath already smitten five radio broadcasters who previously called the virus a hoax, and now He’s dispatched the Pope to make His point. If that’s still too ambiguous for you, just promise me you’ll tune in when the pestilence and locusts show up.

Let’s pivot from Exodus and jump right into Numbers:

Of the nearly 182,000,000 people in the United States who are fully vaccinated, 3,040 have thereafter contracted COVID and died. That’s a death rate of .0017 percent, or about 1 out of every 60,000 infected people.

Meanwhile, the death rate among unvaccinated Americans who contract the virus is 1.6 percent, i.e., a 1 in 62 chance of dying from COVID. That might explain why unvaccinated people represent 99 percent of all those now dying from the virus. Or it could just be a coincidence.

Look, I don’t blame you if you don’t want to get the vaccine. Because you might never get COVID. And if you do get it, you might not get sick. And if you do get sick, it might not be that bad. And if it is that bad, you might not die. And if you do die, well, dying a preventable and senseless death is your right as an American — something my aging father reminds me each spring when he scales a three-story ladder to clean the gutters. Take that, Soviets.

Besides, if being unvaccinated means your principal threat is to other unvaccinated people, then you’re somewhat of an inadvertent hero, like the suicide bomber who blows up his fellow terrorists when the vest accidentally detonates too early.

Hold on; I can feel you pulling away. To spare my readers the burden of authoring yet another letter to the editor complaining that my columns are too confusing, I’ll just come out and say it:

No, I do not believe unvaccinated Americans are biological terrorists. They may be misinformed, self-deluded, walking petri dishes of mutating microscopic death, but they probably can’t be deemed biological terrorists. You can quote me on that.

Indeed, when it comes to our national discourse, we need to lower the temperature, to be less inflammatory, to take a deep breath, and to stop using clichés better suited for describing COVID symptoms such as high fevers, lung irritation, and labored respiration. Yet that doesn’t mean I can’t still express my irritation about your unscientific stubbornness.

Because gallivanting about unvaccinated is like skydiving without a reserve parachute. Sure, you might not need it, but if your main chute fails and you’ve deliberately chosen not to jump with that extra canopy, must I be upset when gravity does its job? Or can I be annoyed when your mangled carcass splatters all over my new patio?

In a recent interview, 19th-Century fictitious English businessman Ebenezer Scrooge expressed his loathsome distaste for anti-vaxxers. “If they would rather die,” he said, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

His words were harsh; I, for one, don’t agree with them. Yet he has a point. Because as long as there exists a critical mass of the unvaccinated, COVID-19 will continue mutating into deadly new viral strains that further justify the preposterous requirement that we all wear masks.

And that’s why, intellectually, Mr. Scrooge can’t be faulted for hoping people either get vaccinated or expeditiously succumb to their infections, since those are the only two means by which we’ll finally ditch these horrendous face-coverings.

It should be noted that Mr. Scrooge really hates wearing a mask. No, like, he despises it. Like, he can’t breathe when he wears it, and it’s really hot and itchy, and it muffles him when he talks and he can’t hear what people are saying and he always forgets his mask in my car and he thinks the whole thing is stupid and he fantasizes about violence every time the flight attendant reminds him that his nose has to be covered. (It’s Ebenezer Scrooge, guys; you know him as well as I do.)

Again, I’m not telling you to get the vaccine; I acknowledge that you’ve yet to finish “doing your own research” on YouTube, Craigslist, and the Alex Jones podcast. Moreover, just because your cell phone already tracks your every move doesn’t mean that lizard people aren’t trying to inject microchips into your bloodstream. And I’ll admit it: “lizard people” is an area wherein my own research is lacking.

But just do me a solid and, if you contract COVID after refusing to get vaccinated, stay out of the hospital. Because on Sept. 27, when New York’s mandate that all healthcare workers be vaccinated goes into effect and thousands of unvaccinated nurses lose their jobs, the demands on the 81 percent of state hospital workers who actually are doing their part to end the pandemic will be enormous.

Nurses are already being forced to work 24-hour shifts across New York at substantial personal risk. And it’ll be hard to thank them for their service when a ventilator tube is pummeling its way down your trachea. So stay home, where at least you won’t have to wear a mask.

Jesse Sommer is a lifelong resident of Albany County.

He welcomes your comments at

.

Curse you, Mark King.

Curse you and your Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy.

Curse you for safeguarding so many of New Scotland’s rural and agrarian traditions, and for ensuring that our Town lives up to its moniker as the “Jewel of Albany County.”

Curse you, Alan Kowlowitz and Dennis Sullivan, for so diligently preserving New Scotland’s rich historical legacy, and you too, Melissa Hale-Spencer, for so faithfully recording in these pages the life and times of every New Scot.

And, while we’re at it, curse all you municipal officials whose comprehensive plans and commercial districts and zoning schemas have conspired to make our hometown something worth fighting for.

A pox on these pillars of the New Scottish identity for having secured a cultural inheritance that’s now incumbent on all of us to preserve and pass on to the generations yet to come. No one asked these relentless busybodies to make our community so special, nor to foist onto our shoulders the solemn burden of defending a way of life against the pressures of modernization and economic exploitation.

So curse you, I say. Thanks to you people, there are countless shows on Netflix I’ll never get to watch, since remaining vigilant in the face of never-ending efforts to pave over our fields and forests is so time-consuming. You guys are jerks.

But what’s done is done. And now that these graying local boomers have gone and opened Pandora’s nostalgic toybox, I guess the first order of business is to figure out what questions should inform our vote in the upcoming town board elections on Nov. 2.

After all, the arrival of the 2020 United States Census data compels serious contemplation. Among other eyebrow-raising data points was the revelation that New York City now accounts for 44 percent of our state’s entire population, after having registered a completely unanticipated increase of 629,000 people since 2010. Well, good for y’all; stay there. There’s nothing to see up here.

Yet the encroaching horde isn’t relegated to downstate. To our north in Saratoga County, towns like Malta, Halfmoon, and Ballston have registered population increases anywhere from 16 to 21 percent in just the last 10 years. Meanwhile, Albany County grew by over 3 percent this past decade, a rate which itself was outpaced by New Scotland’s growth of more than 5 percent (to a total of 9,096 residents). As The Enterprise reported last week, “no other municipality in Albany County saw a bigger jump in its population rate than New Scotland.”

I welcome this influx of an additional 448 inhabitants. In expanding the tax base, patronizing the local business community, and augmenting our neighborhood’s creative energies, these new New Scots have injected vibrancy into a hometown they can now rightly claim as their own. There’s a whole slew of commercial opportunities and quality-of-life upgrades that our new neighbors make possible; their presence powerfully argues for New Scotland’s open-armed reception of those who would follow in their wake.

But it’s also true that what draws people to New Scotland is precisely what could be lost if population expansion continues unrestrained. And in the short-term, as new trappings of luxury enterprise arise to cater to this larger civic community, New Scotland’s appeal will further surge.

So to my mind, there’s only one compound question that matters for our town board candidates — from it, all other inquiries derive. *Ahem*:

Should there be a practical limit on New Scotland’s total population and, if so, what should it be?

Is it the current 10,000 residents? Should it be 20,000? 50,000? Or should New Scotland’s population growth be entirely unconstrained, its hamlets buried beneath an onslaught of cul-de-sacs and memorialized merely as the branding of massive new residential complexes, sporting names like “Clarksville Commons,” “Unionville Apartments,” “Tarrytown Meadows,” and “Feura Bushes"?

A question derivative to the one about population is whether the town board candidates are prepared to utilize the authorities at their disposal to strategically influence our municipality’s size, relying on a mix of development restrictions, zoning regulations, and a campaign to incentivize conservation easements.

To those who would argue that the right of property alienation should be unfettered, unimpeded, and unlimited, I’ll just say this: I hear you, I acknowledge the merits of your perspective, I unconditionally reject it, I extend you my sympathies for having chosen to purchase property in New Scotland when Bethlehem clearly would’ve been a better fit, and I’ll spare us both further lip service, since our positions are deeply-held and philosophically irreconcilable. And I really do need to get back to Netflix.

To those who would argue that logistical hurdles or the town’s natural peculiarities — e.g., lack of municipal water — will inherently prevent significant population growth, I say: “Hold my beer.” Where there’s money to be made, there will always be communities and ecosystems to destroy. Let’s not forget how close we came to the installation of Stewart’s Shops petroleum tanks in the Vly Creek floodplain across the street from an elementary school.

What’s therefore required is the continuation of a proactive and deliberate regulatory regime that channels expansion, construction, and new arrivals in a manner consistent with what makes New Scotland so, well, New Scottish.

Worried that New Scotland Town Supervisor Doug LaGrange wouldn’t give me the exact pull-quote I needed for this column, I elected not to call him for comment. Instead, readers, let’s together conjure a reality wherein, last week — I don’t know, say, on Monday — Supervisor LaGrange courageously strode to the flagpole outside Town Hall and delivered a rousing address wherein he declared, “The town of New Scotland is closed for further development.” Everybody take a second; have we all joined in that shared experience? OK, let’s proceed.

Last Monday, New Scotland Town Supervisor Doug LaGrange courageously strode to the flagpole outside Town Hall to declare that New Scotland was closed for further development. It was a truly audacious pronouncement. I, for one, was shocked.

This so-called “LaGrange Doctrine” has already become a cornerstone of New Scottish domestic policy, antagonizing would-be developers and the capitals of Europe alike. Supervisor LaGrange reportedly remains unperturbed in the face of criticism. “I am a servant loyal not only to my neighbors’ interests,” LaGrange told me by phone, “but also to the interests of those who came before us and those who will one day take our place.”

(Um, yeah, so I forgot about that part. We now also all have to jointly experience a reality wherein I called up Supervisor LaGrange and he said, “I am a servant loyal not only to my neighbors’ interests, but also to the interests of those who came before us and those who will one day take our place.” Which more-or-less sounds like something he’d say, right? Take a second. Got it? Keep reading.)

I readily acknowledge the deeply deleterious impact of restrictions on New Scotland’s residential growth, to wit, housing scarcity. Already, home values in New Scotland are skyrocketing; limits to development will only accelerate this trend. Absent tactical intervention, New Scotland risks someday becoming an elite enclave of smug granola-crunching capitalists and effete self-congratulatory professionals who import the fruits of the very family farms that can no longer afford to operate in town.

But in that case, maybe the solution is to build “up” and not “out.” Maybe the essential question isn’t one of limiting New Scotland’s population, but rather one of fortifying our undeveloped acreage.

After all, I’d love to live on a revitalized east side of Voorheesville’s South Main Street, wherein residents of adjacent four-story multi-unit apartment buildings, row houses, or condos live above first floors inhabited by dry cleaners, hardware shops, convenience stores, and existing staples like Star + Splendor, Purity Hair Design, and Gio Culinary Studio. A neighborhood in the vein of Albany’s Center Square would still afford access to a Blue Ribbon school district without the attendant lateral sprawl that too often devours what would’ve otherwise been picturesque upstate towns.

So perhaps the LaGrange Doctrine requires a bit of reinterpretation. I mean, who does that blowhard think he is, anyway? (OK, I’ll fix it: Now pretend I rang Supervisor LaGrange and he clarified that what he meant to convey is that New Scotland is closed to any further development that results in the destruction or clearing of existing open space, wetlands, and forests. Everybody good? Sheesh, constructing “alternate facts” is way harder than it looks on cable news.)

This reconstituted LaGrange Doctrine should now assist New Scotland’s town, planning, and zoning boards evaluate the application to construct six two-story buildings about a quarter-mile down from Town Hall on New Scotland Road. Yes, the proposed 72 units of affordable housing might offer New Scotland more of the socioeconomic diversity it increasingly lacks, but does it incorporate a due commitment to open space? Irrespective of how this particular matter is resolved, town officials must reconcile ambiguities in the applicable hamlet zoning law with an eye towards the preservation of New Scotland’s bucolic sensibilities. Because once gone, they’re gone for good.

Illustratively, there’s still time to express your thoughts on what to do with the historic Bender Melon Farm, which was saved for posterity by the Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy in 2020. (Visit https://arcg.is/aOHDK to learn more.) And I have no doubt that veterans of the “Big Box Wars” greeted news of the Bender Melon Farm’s acquisition with assured self-satisfaction, having thus firmly consolidated the gains of their 2008 uprising. Yet their achievement has counterintuitively created a back-country paradise that’s now even more inviting to those who would capitalize on New Scotland’s character at its very expense.

So what’ll it be, candidates? In 2050, will New Scotland look like Delmar? Like Clifton Park? Or will it look like New Scotland? And if the latter, what is your plan to shepherd the woodland hometown of today to the one of mid-century?

There’s a reason that New Scotland has long been known as the “jewel of Albany County.” On November 2, 2021, vote for the candidates who will unreservedly pledge to ensure that our jewel shines as brightly tomorrow as it does today — thanks very much to the efforts of those cursed aging boomers who seem to fundamentally misapprehend the concept of retirement.

Editor’s note: Jesse Sommer’s father serves on the New Scotland Zoning Board of Appeals.

Just over 20 years ago, a little past 7 p.m. on June 22, 2001 — after Brendan had concluded his salutatorian speech — I delivered a commencement address as the Class of 2001’s “student speaker” at my Voorheesville high school graduation. I presumed its text lost to history until I came across a wrinkled copy while cleaning out my parents’ attic the summer before last.

And here in the Altamont Enterprise’s “Keepsake Graduation Edition,” I’m letting this artifact from the twilight of my adolescence see the light of day once more. Because while I wouldn’t expect the Class of 2021 to heed whatever advice I might dispense now, maybe insights from back when I was cool will have some value.

Or maybe not. Back then, I had urged my fellow graduates to live each day like it was their last; now I wish I’d begged them to live each day like they’re about to be 40. Life hits different when you reach your late thirties, and it turns out that aging entails going to sleep each night healthy and sober only to wake up each morning inexplicably injured and progressively more hungover.

Yet if “be kind to your knees and liver” is insufficiently inspiring, then the speech I gave before any of you 2021 graduates were even alive is probably a better fit. At the very least, what follows might equip you to extrapolate a bit — to discern a snapshot of future selves that have been similarly ground through the gears of time.

A few preliminary admin notes, as facets of my two-decade-old remarks warrant disclaimer:

First, certain sentiments in my address suggest either that the censors were asleep at the switch, or that our diplomas had already been distributed. Take my nuggets of wisdom with a grain of salt. You wouldn’t heed life advice from the attention-seeking miscreant who sat behind you in math class, and that guy is a lot like the 18-year-old who wrote this speech. Periodt, no cap.

Second, rather than indict the cringey privilege that my speech radiates as a function of its pre-social media ignorance of other people and places, celebrate how unwittingly insulated from life’s most dire struggles my classmates and I were within our cocoon of woods and wildlife, friends and family, and a caring community.

Yes, I’ve met fascinating people and learned so much since my moment at that podium, but there’s also a lot about the world beyond New Scotland that I’ll never unsee, try as I might. So graduates, before you set off to greener pastures, organize your photos and journals to more efficiently look back at what you may yet come to realize was the unparalleled blessing of a youth in New Scotland.

Finally, my speech betrays signs of a creeping chronophobia that now cements every facet of my personality. But consider how justified was that anxiety about time’s passage. My speech was delivered in a world just after Columbine but just before September 11th, in a world after Challenger but before Columbia, after AOL but before Google, after pagers but before any device denoted with a lowercase “i.” All those dates and devices materialized before your Class of 2021 identity came into being, as so much trivial grist for your U.S. History homework assignments.

But it was all real to me, once. And so, too, will you Gen Zetas conceive, experience, devise, and reinvent a reality that exists between now and your own address to the Class of 2041. The reality you inhabit now will someday seem only distantly familiar — an ephemeral moment in time memorialized only on dusty old wrinkled papers in your parents’ attic.

Assuming, of course, that paper is even still a thing. Without further ado:

****

One of the tragedies of life is that time doesn’t stop. It’s hard to believe that once, a long time ago, I stood shoulder to shoulder with the very people now behind me, a kazoo in my mouth, eyes staring intently at Mrs. Fiddler, as I joined the newly designated Class of 2001 in singing “Mairzy Doats” and “Zip Up Your Zipper” at our kindergarten graduation.

Back then, I must not have realized that one day I would be leaving the people with whom over that past year I had become friends, and with whom over the next decade I would share my greatest childhood experiences. Back then, learning Mr. M’s theme song was the most important thing to me. Sometimes, I wish it still were.

I can’t remember why I wanted to grow up so fast. The world didn’t look so bleak when I was younger. I watch the news, I listen to my parents talk, I discuss current events with my teachers, and I realize that this is not the world I want to be a part of. I don’t understand school shootings, price wars, political correctness, economic concerns, or the AIDS virus. I never want to understand these things. I’d do high school all over again, exactly the same, if it meant I could be carefree and without the responsibility of making serious decisions just one more time.

Here we are, the Class of 2001, graduating again, before the very people who watched us take our first steps towards the big yellow limousine on that first day of school, and who must now watch us take our first steps towards the real world, and all that lies ahead. My kindergarten graduation was filled with a sense of anticipation, serving as a stepping stone for all that I would learn in the Voorheesville school district. Time passed at breakneck speed, and now, here I am today, at my high school graduation, watching one of the most significant chapters in the book of life come to a close.

Look to the sunrise with anticipation, look to the sunset with a sense of reflection, but don’t look at the midday sun; bright light is damaging to the retina. In other words, between the beginning and the end, think of neither; just enjoy all that the middle of your journey has to offer.

And that is my message today to all the underclassmen who’ve heard over and over that high school will be over before you know it. Although true, I won’t repeat the message, since it did nothing for me when I first heard it. The end will come soon enough, and when it does, you’ll realize that high school was just four years out of a life that may last 20 times as long. On the contrary, I urge you not to heed the ending of high school, for if you live [grades] 9 through 12 anxiously awaiting this final day, you’ll miss the countless beginnings that characterize every second of your life.

High school isn’t just your teachers, your books, your sports teams, your clubs, your family, or your friends. High school is you, at a certain point in time, when the world was still new to you, and every September brought a change in faces and a score of new questions waiting to be answered. Your schoolwork is not the aspect of high school you’ll remember when you’re behind the counter, or building someone’s house, or cramped in your office staring at paperwork. It is that age you will remember, and all the defining moments that went with it. Your first kiss, your senior prank, the independence that came with a driver’s license, the special friends you were with when trying to buy booze illegally for Friday’s party, and the discussions about a world that you had yet to fully understand around the cafeteria lunch table.

Underclassmen, here’s what little insight I can offer with some authority: Voorheesville is a great place to grow up if you know how to take advantage of the benefits. You have a sheltered community surrounding you, and parents who, ideally, will support you as you journey through adolescence. This is your time to make mistakes. This is the time to experience what being a teen is all about, while you still have people to care for you right around the corner if you get in too far over your head. At this age, you’re not only allowed to be stupid and ignorant, it’s expected! You have precious little time to enjoy this age, so I beg of you not to sweat the small stuff, to take the risks today that you might not tomorrow, to go after the things that bring you joy, and to not get hooked on any one source of pleasure since, when you’re young, there’s something new and magical at every turn.

Do the right thing. The right thing may not always be the popular thing, the legal thing, or the accepted thing, but it is the moral thing, the important thing, the thing you’ll smile about at the reunions when the only thing all you old people share is the common bond of prior youth. Please be safe, and relatively smart. Otherwise, you might not make it to that reunion at all. Parents, be understanding, but kids, give your parents a break. While you’re deciding what shirt goes with which shoes, they’re paying the bills and wistfully remembering their own childhood exploits that, let’s face it, are probably twice as “heroic” as yours.

Now, fellow graduates, we’re about to be those nagging, bill-paying parents. I have no idea how I’m going to cope with that. Here’s some advice that at least sounds right.

Every time you think life couldn’t get any better, take a moment to reflect that you’re being watched as you enjoy yourself, by the future you that longs again to be carefree and rebellious in a manner that’s wonderfully innocent and pure. Live for the moments you’ll carry with you into a future you can worry about tomorrow. Have something to look back on when you’re thrust into this odd world. If you have fun in the present, you’ll have fun in the future, reliving the past through memories that bring you joy.

High school was nothing but a quest to find out who we were. Whether we discovered the answer was not as important as the voyage itself. And to the students here today who will walk across this very stage in years to come, don’t ever close your eyes to yourself or all that’s around you. Except when you’re sleeping. Definitely get enough rest. Life passes you by when you can’t stay awake. Savor the fact that, for just a couple more years, 99 percent of the time there won’t be anything so important that we should lose sleep over it.

Today we see black and white. We know everything. We may be dead wrong about our assertions, but at least we’ve taken a stand about something. Along that road of life, we’ll begin to see gray, and understand less and less about the world and the 6 billion people with whom we share it. We must embrace this uncertainty. However, now is a time when the most stressful inquiry about our existence could be answered with a “whatever.” Let’s enjoy that. It’s fleeting.

If you look at the future in any way but as a dream, you’re taking your life for granted. What if there is no tomorrow? Life is a commodity, and every day you wake up, you should say to yourself: “I’ve been given another chance to live life to the fullest, and so I’ll live today as though it were my last day on Earth.” Unlike your parents and teachers, you have your whole life ahead of you. Don’t rush it. You’ll be in their shoes before you know it. Think about how fast high school went. The years will really start flying when we get older, when we don’t progress to the next grade level, when there are no summers off, when every day feels like the day before it.

If you live your life for the future, you’ll never live at all. You’ll only be a teen once, but may the experience you extract from this age be one you enjoy so much that you’d live it all over again. Once and forever: a teen.

****

I finished my address with a flourish, throwing two roses into the audience, one in honor of a beloved teacher, the other in honor of an adolescent crush. As I returned to my seat, I remember taking a second to feel my future self looking back at me. Here I am now, doing precisely that.

Yet as I write this, I’m suddenly less interested in what “future me” has to say, and instead listening to that “past me.” Life isn’t as certain as I thought it would be; hearing past me’s passionate insistence that I live for the present and surrender any entitlement to some unpromised future is phenomenal advice that, along the way, I somehow forgot to take.

Ladies and gentlemen of the Class of 2021, take a second to meet the gaze of “2041 you.” Do you recognize what you see? He or she boasts the lingering influence of classmates who will very soon recede into your past, but who were nonetheless instrumental in shaping the 38-year-old you’ll soon become. Yet rather than straining to hear what he or she has to say, maybe now is the time to whisper the innate guidance that, someday, you’ll finally be wise enough to take.

Go forth and find out where you belong. For me, a wild 20-year odyssey is finally taking me back to Albany County. Word to Dorothy: What I set out in search of was right where I left it, back home. Sometimes it be like that. No cap.

Location:

As we prepare to bid June adieu, it’s worth tying together a few historical threads that tangled in this, the first month of summer. That’s the lofty status most of us primarily associate with June, despite the shadowy abstract authority that somehow imbues these particular 30 days with a slew of other significances.

For example, June is Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual Pride Month. More commonly referred to by the shorthand LGBTQIA, this ever-expanding initialism currently clocks in at nearly 27 percent of the entire alphabet.

Or, following President Obama’s 2009 update of the antiquated “Black Music Month” created by President Carter in 1979, June serves as “African-American Music Appreciation Month” — celebrating the legacy of those who “lifted their voices to the heavens through spirituals” amidst the injustice of slavery — while simultaneously offering the perfect backdrop to last week’s institution of Juneteenth as the first new federal holiday in 38 years.

And, coming on the heels of Albany’s deadliest month (there were six shooting homicides in May alone), June is also Gun Violence Awareness Month. Which brings me to an Albany Common Councilman’s call this past January to change Albany’s flag.

Stay with me.

Back in the heady days of a brand spanking new New Year — before the Capitol Siege and an inadvertent Suez blockade, before the spectacles of impeachment and inauguration, before the death of a King (Larry) and a Prince (Phillip), before Kim divorced Kanye and the vaccine finally freed us to expose the bottom third of our faces — Councilman Owusu Anane introduced a resolution to examine whether New York’s capital should continue flying a flag whose original inspiration was adopted by Nazis (who, to put it mildly, ruin everything).

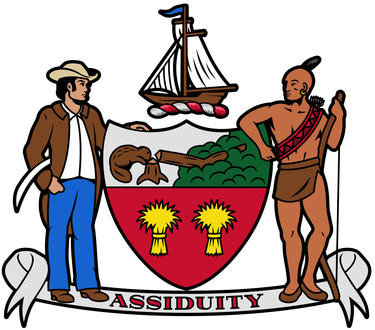

Anane was parroting a cause championed by Adam Aleksic, whose online petition at www.AlbanyFlag.com advocates redesigning Albany’s current city flag, which was first introduced in 1909 as part of Albany’s tricentennial celebration of Henry Hudson’s discovery of the river that — wouldn't you know it — bore his name.

The flag’s design had intended to emulate the so-called “Prince’s Flag” (of Prince William of Orange fame) flown by the Dutch East India Company for which Hudson sailed in 1609. With an eye towards history, Albany adopted the horizontal orange-white-blue tricolor, replacing the Dutch East India Company’s logo with the city’s own coat of arms.

And that might not have been problematic if Albany’s coat of arms — adopted in 1789 — didn’t look as though it’d been designed by a xenophobic third-grader using clip art from Microsoft Windows 95.

“Vexillologists (flag experts) have five rules of good design,” Aleksic wrote in a letter to the Times Union late last year. “A flag should be simple, use no more than three basic colors, contain no lettering or seals, have meaningful symbolism, and be distinctive from other flags.” Albany’s flag fails on all counts.

To his credit, Aleksic accompanied his criticism of Albany’s flag with a proposed design for a new one, and urged Albanites to “make a bold change and choose to promote unity and commonality instead of this unknown, intolerant eyesore.” (To his further credit, he used the word “eyesore,” which now grants me a not-to-be-missed opportunity to declare that Evan Blum should be ashamed of his cynical abuse of the legal process to forestall action on the Central Warehouse.)

Even absent the coat of arms squarely centered on Albany’s flag, the tricolor Prince’s Flag has the awkward distinction of having been: the colors of the slave-trading Dutch East India Company; a backdrop for the Dutch Nazi Party in the 1930s; the base flag design for South Africa’s 20th-Century apartheid era government; and the current pattern of choice for worldwide white supremacists. Whoops. Where’s that cartoon-style “sweaty collar-pull” emoji when you need it?

When you add that coat of arms back in, things get downright uncomfortable. That’s why Aleksic and Anane aren’t alone in their distaste for the centerpiece design of Albany’s seal. Indeed, Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan has already stopped using Albany’s seal on official letters and documents unless legally required to.

What force of law might so compel her? How ’bout the fact that the seal’s coat of arms design is enshrined in § 15-1 of Albany’s city charter, which rather embarrassingly describes the dude on the right as “an American Indian, savage proper.” Gulp; collar-pull.

No wonder Aleksic calls Albany’s flag “a racist, poorly designed symbol that isn’t instilling pride in our residents.” And, while it’s perhaps unreasonable to expect every quarter-millennium-old art project to age flawlessly, it’s also unreasonable to go another 250 years before taking action. I mean, this isn’t the Albany Central Warehouse, am I right? (Ba-ZINGA!)

Whereas tackling the design of Albany’s coat of arms may be more legally daunting, replacing Albany’s flag needn’t be. I already mentioned Aleksic’s draft flag design, which you can see on AlbanyFlag.com. It’s snazzy, simple, and sleek — exactly how’d you describe Albany if you spent three straight hours drinking-with-a-purpose at Fort Orange Brewing down on North Pearl Street.

Why the gratuitously-contrived commercial endorsement? Because Fort Orange Brewing’s namesake antecedent offers inspiration for a new Albany flag that might even be superior to Aleksic’s proposal.

In 1624 — exactly 40 years before it was renamed Fort Albany — Fort Orange emerged in the midst of Mohican territory as New Netherland’s first permanent Dutch settlement. It was named in honor of the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau, from which Prince William of Orange had emerged just a few decades prior to kick-start the Dutch revolt against the Spanish.

And when the English took control of the fort in 1664, they inherited a simple concept for that someday capital city’s future flag — unforgivingly obvious, right there in the name.

Because what if Albany’s flag were just — orange?

“That’s outrageous!” you scream, since change is scary and it’s fun to be loud.

Think about it. The simplicity of solid orange would make our flag uniquely defining; Google reveals no other national, provincial, territorial, state, municipal, or organizational flag composed of a single solid orange.

“Lock him up! Lock him up! Lock him up!” you chant, increasingly confused as to why.

Well, just hold on a second. Think about my proposal in the context of June.

There is one cause, one commemoration, which is inextricably linked with orange: National Gun Violence Awareness, for which orange is the official color.

Among other less imperative distinctions, June is Gun Violence Awareness Month, and it just so happens that right now, “Cap City” is grappling with a second year of unprecedented lethality. Cap City also finds itself in need of a new flag.

Gun deaths in 2021 are already on track to beat the record set last year, during which 129 people were shot — 17 of whom were killed — in one of Albany’s most lethal years on record. (And, in a tangentially eerie report linking my current whereabouts to life back home, the Times Union also reported last week that a handgun used in four Albany shootings from 2017 to 2018 had actually been stolen from Fort Bragg, North Carolina.)

So let’s acknowledge the synergistic trends intersecting at this particular point in time and space. Can the cause of reducing gun violence spur a long overdue replacement of city icons, and vice versa? Can we eliminate the ancient indignities depicted on our guidon while working to spare mothers the devastation of needlessly burying children caught in the crossfire?

National Gun Violence Awareness Month does not mean that June is open season for mass confiscation of personally owned firearms. And celebration of LGBTQIA communities or African-American music doesn’t mean that June is officially the month where we set out in search of state symbols to skewer.

But, like, come on; the seal of Albany features a Dutch farmer, a Mohican warrior, a beaver, and a boat. Can’t these concepts almost be better represented by the color orange, which harkens back to those courageous New World adventurers — instilled with the revolutionary spirit of William of Orange — who constructed a foothold in the heartland of the proud Mohican confederacy?

And, like, do we need a tricolor flag, when a solid orange one would symbolically align Albany’s identity with our life-or-death struggle to eradicate the horrendous gun violence plaguing streets in the heart of state government?

These are the questions. And sometimes the answers are right in front of you. Other times they’re on the label of the locally-branded beer you’ve been drinking, which you notice for the first time only after your third hour at a bar on June’s summer solstice. But regardless of how you arrive at those answers, orange you glad I didn’t say “Central Warehouse?”

Captain Jesse Sommer is an active duty Army paratrooper and lifelong resident of Albany County. He welcomes your thoughts at jesse@altamontenterprise.com.

The news yesterday spread faster than the fires that twice engulfed Albany’s Eyesore in the last 11 years: Albany County has listed the Central Warehouse for auction.

Within an hour of the Times Union’s bombshell report that the county had seized the initiative to auction off the Central Warehouse, News 10 had picked up the story. The Albany Business Review wasn’t far behind.

By 9 p.m., reactions on social media had exploded, which, as a description, conveniently segues into yet another plea for this wretched structure’s detonation.

“They never contacted me,” building owner Evan Blum told a reporter for the Albany Business Review, vowing to fight the county’s planned auction. “I don’t even know how they have the right to do it. You would think there would be a process to do that.”

As it turns out, there is a process “to do that,” and Mr. Blum would’ve known the county had the right “to do it” had he been an Altamont Enterprise subscriber. Because this past January, the Enterprise followed up on my inaugural call to demolish the Big Ugly Eyesore by urging Albany County to enforce the half-million-dollar tax lien.

Citing applicable provisions of New York’s Real Property Tax Law, the Enterprise meticulously detailed Mr. Blum’s reprehensible inaction throughout the four years since he’d purchased the building, and demanded that local officials do something.

That is the real story here.

Albany County’s dramatic maneuver to auction the building (check the listing available on its website) is the first salvo of what will be an arduous process. Yet it already reflects the efficacy of community mobilization through the auspices of local media. In affording a forum within which to advocate for action, the Enterprise’s continuous Central Warehouse coverage helped raise awareness and mobilize a response.

But it couldn’t have done it alone. In a seeming “high five” from the opinion pages on opposite sides of Albany’s weekly vs. daily print media divide, last month I penned a letter to the Times Union editor commending the “apparent turnabout by one of Albany’s most visible commentators,” who had a month prior finally acknowledged the wisdom of knocking down the “ongoing safety problem.” In this case, the nexus between government action and a hometown’s media echo chamber is hard to refute.

That’s because local newspapers are uniquely suited to identify long-standing controversies and involve the public in their resolution. They focus attention and, thereby, resources to improve communities. Citizen involvement matters; the Enterprise and her sister publications continue to channel it. Sure enough, local officials listened, considered, researched, and finally took action.

And that’s the other facet to this story. It’s easy to forget that our municipal officers are themselves members of our community, selected to advance the constituent interests they reflect. Their jobs are thankless, contentious, and — once the campaigns are over — unglamorous.

So it’s important to recognize our elected, appointed, and otherwise dedicated public servants for jobs well done. Indeed: in this and so many other ways, the McCoy and Sheehan administrations are a credit to our county and city interests.

Except that now it’s time for more whining, because that’s the sound “pursuit of happiness” makes.

“I got no due process,” Mr. Blum told the Albany Business Review, conveniently forgetting the three-day trial in Albany City Court earlier this year wherein Judge Helena Heath fined him $78,800 for a slew of code violations. Resorting to a novel tactic he’d most recently used to address his overdue tax bill, Mr. Blum — drumroll please — didn’t pay the fine.

“I’m not the bad guy,” Mr. Blum declared to the Times Union, sounding very much like the bad guy. He warned that, if the county sold the building, the new owner would be “some slob who doesn’t do much for the city,” in what neutral observers are describing as the most self-unaware pronouncement of 2021.

But if Mr. Blum’s latest proposal — to wit, that the building’s massive blank exteriors be adorned with a “continually changing ‘mural show’” — sounds delusional, it pales in comparison to our local government’s bated-breath expectation of a knight-in-shining-billions.

Because right on schedule, Albany County spokeswoman Mary Rozak announced that Albany hadn’t “given up hope” for “a person who will be the right fit, who has a plan that will put the building back on the tax rolls.” Meanwhile, over at City Hall, Chief of Staff David Galin heralded Mayor Kathy Sheehan’s confidence that “the private sector will step up and make a compelling proposal for the site.”

An aside: One of the limitations to the written word is that it doesn’t satisfactorily convey furiously desperate shrieking. So readers will just have to use their imagination when I reiterate that DEMOLITION. IS. THE. ONLY. FEASIBLE. OPTION.

Deep breath. Calm. Let’s take a beat; walk with me here.

History repeats itself

Thanks to gracious research assistance by Carl Johnson, longtime publisher of Hoxsie — an online magazine that celebrates Capital District history — I was able to ascertain that the Central Warehouse was constructed by a company known as the Central Railway Terminal & Cold Storage Co. Inc. (An advertisement in the Knickerbocker Press on May 4, 1927 announces the offer of securitized equity in the building.)

But just shy of seven years ago, a gentleman by the name of Eugene B. O’Brien advanced a slightly different origin story in a comment to an article about the Central Warehouse on the once beloved but now defunct “All Over Albany” blog.

“I believe the Central Warehouse may originally have been built by what was, in 1916, the Albany Terminal Warehouse Company,” he wrote. “My great-grandfather, John F. O’Brien, who was also a New York Secretary of State in the early years of the last century, was its President. By 1930, the organization’s name had changed slightly, to the Albany Terminal and Security Warehouse Co. My grandfather, John L. O’Brien, Sr., who died in 1980, was its President.”

I was unable to corroborate the Albany Terminal Warehouse Company’s authorship of the Eyesore. But John F. O’Brien was indeed once New York’s secretary of state, and an advertisement published on a dusty old page of this very newspaper on Jan. 31, 1969 identifies John L. O’Brien as the president of the Central Warehouse Corporation, which New York State records reflect as having an initial Department of State filing date of July 23, 1935 and a dissolution effective Sept. 29, 1993.

Regardless of how these marginally conflicting accounts ultimately reconcile, the reason this history is important — the reason I remain so obsessively insistent on consolidating the Central Warehouse’s record in easily recallable columns — is that resolutely documenting the Central Warehouse’s trajectory is the most effective way of illustrating how hopeless is the promise for its supposed modern-day potential.

Yes, there was once a use for that building, ladies and gentlemen, just as there was once a use for the telegraph, kerosene lamps, and phones produced prior to 2013.

But that’s all behind us now. Each time we try to envision or reinvent a use for this disintegrating structure, we confront the Eyesore’s history — and specifically, the one that incessantly keeps repeating itself. Just look at what Matt Baumgartner, Albany’s most defining Gen X serial entrepreneur, wrote on his Times Union blog back in June 2009:

“[R]ecently I have heard that some big development company bought [the Central Warehouse] and is planning on turning it into apartments or condos or whatever, with storefronts at the bottom. Every night before I go to bed, I ... pray to Jerry Jennings that this rumor is true. Wouldn’t that be FANTASTIC for Albany?! To have beautiful, modern, riverfront, sustainable condos in that building?”

Different mayor, same pipe dream.

Please: Re-read my past columns about the warehouse. I’ve documented each and every one of the failed endeavors that have successively burdened us with false hopes that delay the inevitable.

Just for sport, here’s another entry in the sordid tumble of developers thwarted by the Big Ugly’s uncompromising intransigence: After Trustco Bank acquired the Central Warehouse at a foreclosure auction in 1996, it sold the building to Frank Crisafulli, a retired owner of a food-distribution company, for $1 and approximately $120,000 in back taxes.

Add that to the other ten transactions I’ve previously detailed. Fellow Albanites, for the sake of whatever sanity has yet to slip through our fingers, I’m throwing down the gauntlet. I dare you to make something of this sinister slab of concrete.

Promise me

For readers accessing this column online — here:

Take both sets of blueprints to the building I’ve collected!

Take the architect’s original building designs!

Take Albany County’s complete summary of the building’s recent transactions, property description, contaminant profile, and tax maps!

The only thing I plead with you not to take — you intrepid pie-in-the-sky property developer heaven-sent to answer Matt Baumgartner’s prayers from over 10 years ago — is time.

Look, you win: I’ll do it, guys. I’ll take the plunge. I’ll cross my fingers and join everyone for a 60th instance of believing something practical, meaningful, wonderful can be done with an edifice that has blighted Albany’s backdrop since before the grandparents of those county and city spokespeople were born.

I’ll give you six more years of faith that we can finally rehabilitate the historical relic that now threatens to mutilate the views of our new skyway park. But in return, you give me your word:

THIS. IS. THE. LAST. TIME.

If we still haven’t found a developer to manifest our hopes and dreams by May of 2027 — 100 years after the Knickerbocker Press announced the arrival of that brand new Central Warehouse — let’s jointly commit to dropping the Big Ugly Eyesore like the bad habit it’s become.

That means lining up the C-4 now, folks. Because the next smooth-talking out-of-towner is right around the corner, peddling lofty promises and fuzzy math, ready to do nothing with that building but give me something to kvetch about.

Captain Jesse Sommer is an active duty Army paratrooper and lifelong resident of Albany County. He welcomes your thoughts at [email protected].

I was 11 when my uncle died, unexpectedly, in 1993 at the age of 42 — just a few years older than I am now. I don’t remember much about him, sadly, aside from a couple scattered memories of his zany brilliance.

But I vividly recall the funeral, and how my dad — whom I’d never before seen cry — gripped the lectern as he recounted the countless times that, growing up, his older brother deliberately made him laugh so hard at the dinner table that milk would come out his nose. It was now just another of their many childhood anecdotes that would never again be shared with its co-author.

If I ever appreciated that “Uncle Scott” was my father’s brother, I did so only abstractly; there was no reason to perceive an identity prior to and independent of his primary role in my life. Yet before he was my uncle — and far more importantly — he was my father’s only sibling. And though Dad was already a husband and father of four back in 1993, I imagine the meaning of “family” wasn’t quite the same for him after Scott took off.

I’ve never talked to Dad about his big brother’s passing, and I don’t intend to. That would force me to confront a central anxiety which, thus far, I’ve managed to suppress — even as it simmers beneath the reason I write this column in advance of a holiday you might not be tracking.

Saturday, April 10, is National Siblings Day. The commemoration was conceived in the United States by Claudia Evart to honor the memory of siblings she lost in separate tragic accidents — one of which ripped her 19-year-old big sister, Lisette, from her life when she was 17, and another of which then stole her 36-year-old big brother, Alan, 14 years later, in 1986.

Without warning, Ms. Evart was suddenly rendered an only child, just as my dad would be seven years later. She responded to that crushing heartbreak by dedicating her life to the establishment of a national day to honor siblings.

I empathize with the ferocity of her mission. After all, but for the untimely catastrophes that tear siblings away from people like Ms. Evart and my dad, the bond between brothers and sisters will likely define the longest relationship a person has in his or her lifetime.

So, curious as to the status of her work, last week I fired off a Hail Mary barrage of messages via LinkedIn, Facebook, and email. We finally connected only when Ms. Evart returned the voicemail I left after finding her phone number through the phone book, thereby marking the very last time in human history that anyone will ever again resort to such antiquated lunacy.

And in yet another illustration of how this column practically writes itself, Ms. Evart informed me during our call that she was once a fellow Albanite, having lived right down the road from where you’re reading this column as a student at the State University of New York at Albany. Because of course she was. (That revelation dropped my jaw, and forthwith justifies Albany’s designation as “Sibling City.”)

In discussing the commemorative day she’d pioneered, Ms. Evart was laser-focused on her unfinished task: securing a Presidential Proclamation from the Biden Administration that would once and for all enshrine formal observation of a National Siblings Day.

It’s the only mountain left to climb. Because since 1995 — and through the auspices of the not-for-profit Siblings Day Foundation she founded to advance her cause — Ms. Evart’s tireless efforts have resulted in the official observance of Siblings Day by 49 of 50 states (California is the lone holdout), as well as celebratory “Presidential Messages” by presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama.

Unofficially, the day is already societally entrenched. From Facebook newsfeeds to the far-flung corners of Oprah Winfrey’s media empire — to say nothing of “Big GreetingCard,” that most notorious of America’s industrial cabals — April 10 boasts exclusive currency as the day our nation honors siblings.

I asked Ms. Evart what Enterprise readers could do to further the objective she’s been advancing for more than a quarter century. She said that, while the most obvious form of support is tax-deductible donations through www.SiblingsDay.org or SDF’s just-launched GoFundMe initiative, equally helpful are the “it-only-takes-a-minute” public pressure and awareness campaigns that supporters can execute from the comfort of their web browsers and mobile apps.

“Lobby the White House through Twitter,” Ms. Evart instructed, directing me to SDF’s twitter handle and encouraging users to tweet the official “@WhiteHouse” account with pleas for federal recognition of National Siblings Day. “Connect with SDF on Facebook and Instagram, so we can demonstrate this movement’s support.”

She also agreed that asking local, state, and congressional representatives to join her in calling on the Biden Administration to declare April 10 as “National Siblings Day” would significantly enhance the organization’s prospects for success.

“This is a contentious time,” she told me. “Formalizing a day that honors unconditional love [among siblings] and which already exists in practice nationwide would be really meaningful right now. Nearly 80 percent of Americans have at least one sibling — it’s a fundamentally bipartisan issue!”

Ms. Evart’s quest so resonates with me because a federally-recognized day to honor siblings would annually commemorate the most important people in my life. I’m the oldest of four, blessed to have three baby sisters who followed my arrival in rapid succession.

The derivative benefit of my mother’s renowned obsession with babies’ chubby cheekies (four sets in five years) was a brood so close in age that, throughout early adulthood, my sisters and I could roll up to Lark Street’s bars as a motley and self-contained clique.

Years before that, in 2001 — when the four of us were jointly confined for eight hours a day in Voorheesville’s Junior-Senior High School — my weekly responsibilities included flagrantly violating my hall pass to distract Robin and Brenna from the doors of their classrooms, only to then goof off with Caitlin in the percussion section of concert band.

Granted, I spent most of my teen years completely ignoring my siblings, because they were annoying and stupid and dumb and annoying. So adolescence didn’t afford me much perspective to appreciate the development of their identities in live-time. But, in retrospect, I was right there alongside them as they grew into the wonderful women I know today.

From the same parents, we each became our own independent people, while sharing so many threads and eccentricities in common. Even now, our every conversation advances the ongoing inside joke that, in the whole universe, only the four of us know.

While I can’t lay claim to ever making milk involuntarily burst from my siblings’ noses, I’m sure Uncle Scott would’ve nonetheless been proud to watch the nightly sabotage of my parents’ attempts at a civil dinner as I perfected the performance art of making my sisters laugh.

Though the military granted me a title, the honorific of which I’m most proud is “brother.” And in that role, it’s been endlessly rewarding to watch my fellow parental progeny forge their own paths from infant to individual.

Over the last half-decade, I’ve even been promoted to the rank of “Uncle Jiss,” solemnly serving as the same mischievous influence my sisters recall from childhood to my adoring nephews and nieces, whom I’ll forever regard as just free-floating pieces of the siblings I so cherish.

I wonder: How did Ms. Evart convert her pain into inspiration? How did Dad so bravely embrace the unexpected burden of keeping alive the boyhood memories his brother once helped him shoulder? And how will I know true happiness or weather life’s losses without having all my siblings there beside me?

Am I allowed to ask God — softly, subserviently, without making any sudden movements — that my sisters and I be permitted to experience together the many joys and tragedies yet lying in wait?

A tangible example: Long after we’ve said our final goodbyes to our parents, the best of them will still be reflected in my siblings, who radiate my mother’s compassion and my father’s wit. And since it’s in retelling the legends of mum and dad over whiskey that my parents will live on, can I respectfully request that God not take my sisters from me until the bitter end?

The answer, I know, is no. Ms. Evart and my father are testament to life’s sole lesson: Nothing is promised, except that it’ll all be taken away someday.

For Ms. Evart, a National Siblings Day will only ever serve as a memorial — a realization driven home when, at the end of our call, she said: “Be sure to give your sisters a big hug the next time you see them.”

How’s that for sobering? Yes, I have the enviable luxury of hugging my sisters.

So, rather than fear their hypothetical loss, I suppose I should instead count the blessing that, this coming Saturday, I’ll be wishing them “happy Siblings Day” in the group text thread that crackles with life all day every day, while taking a moment to thank God for having already given me so much time with the coolest humans on Earth.

I hereby dedicate this column to the siblings in our midst who’ve lost their own brothers and sisters, be it to death, addiction, mental illness, irreconcilable disagreement, or whatever else obscures that most sacred of bonds.

I honor the self-reliant bravery of those who never had siblings, and who thus met the world each day without the affirming (and often humbling) influence of a person who always had your back while simultaneously pronouncing that tormenting you was their exclusive purview.

I commend my dad for reassembling the shattered pieces of his heart, though one has been missing for nearly 30 years. And I thank my sisters for this anecdote:

I was once at a bar in North Carolina, my confidence flowing as freely as the bourbon which fueled it. I don’t remember exactly what I said through my Casanova haze to the enchanting woman I’d just approached, but the pronounced roll of her eyes suggests it was inordinately witty and brilliant.

“You must have sisters,” she said after a pause, smiling.

“I do have sisters,” I replied, bemused by the non-sequitur. “How’d you know that?”

“Because all boys who hit on women in bars are insufferable,” she said, placing a charitably condescending hand on my cheek. “But at least the ones with sisters know how to do it respectfully.”

It remains, to this day, the nicest compliment I’ve ever received. Although the enchanting woman evidently lacked an appreciation for witty and brilliant overtures, our encounter nonetheless left me beaming. Because even when sauced, somehow I still proudly exuded my sisters’ influence.

And maybe that’s the answer. Maybe that’s how Claudia Evart persevered, how my Dad managed to navigate his anguish, how I might survive if one of my sisters didn’t. Maybe siblings remain indivisible parts of us, no matter what coast they’re on, whether on the phone or in our dreams, with us in this life or the next.

Maybe that’s how Ms. Evart found the strength to bring her noble advocacy to the doorsteps of yet another presidential administration, or how Dad figured out how to laugh even when the other party to his life’s most hallowed inside jokes was laid to rest in a synagogue cemetery.

Maybe a sibling’s resilience comes from having endured so many squabbles, practical jokes, and efforts to defraud them of their trick-or-treat hauls. Maybe siblings live on so as to ensure that a piece of their departed brothers and sisters do as well.

Whatever the answer, I’m just relieved that I haven’t had to figure it out yet — that, for me, National Siblings Day is a celebration of those still here. I’m sorry the same can’t be said for my dad, to whom I’m just so grateful for his role in creating my sisters.

They’re the greatest gift my parents ever gave me.

Captain Jesse Sommer is an active duty Army paratrooper and lifelong resident of Albany County. He welcomes your thoughts at jesse@altamontenterprise.com.

The Emperor has no clothes. But does it matter that he’s naked in public?

As the $1.9 trillion federal stimulus bears down on us, forgive me for saying aloud what you’ve suspected all along. Deep down, you’ve always known that America was never going to repay its $28,000,000,000,000 national debt. Like, when push came to shove, you knew that’d be impossible. And why question yet another stimulus check when there’s such a vital need?

But for those who’ve never considered the breathtaking fraud of our global financial system — or, for those who have considered it and now fear it’s all about to come crashing down — let me explain what’s really going on. Fortunately, your anxiety is misplaced; by the time our national debt becomes something to worry about, you’re going to have a lot more to worry about.

Conjure in your mind that mid-1700s colonial society wherein a farmer seeks to buy a pair of wool socks from the local tailor. The farmer barters for the wool socks with a block of his cheese, and the tailor — who really likes cheese — agrees to the trade. But, there’s a caveat (because there’s always a caveat with tailors, am I right?)

“It takes me more time to make socks than it takes you to make cheese,” the tailor says, pretentiously. “And because it’s more of a hassle for me to obtain wool, spin it to yarn, and expertly weave it into a pair of socks than it is for you to just let some milk curdle, then” — and here the tailor makes his move — “if you want this pair of wool socks, you’ll have to give me two blocks of your cheese.”

“But I haven’t got a second block of cheese,” the farmer protests.

“Oh,” the Tailor replies. “Then you can’t have my socks.”

“But it’s cold outside,” the farmer wails.

“Tell you what,” the tailor responds, mercifully. “I’ll give you this pair of wool socks now in exchange for a single block of cheese, but — you owe me that second block of cheese within a month.”

The farmer gleefully agrees to his debt-financed part of the deal, walking off with both a pair of wool socks and an obligation to deliver unto the tailor a second block of cheese. Meanwhile, the tailor gets a block of cheese plus an “IOU” good for a second one within 30 days. Transaction complete.

What I’ve just described is the type of transaction that’s defined most of historical commerce (or, so goes the ubiquitous myth). In societies where a money system evolved, those little coins or paper instruments served merely to make more efficient the process of trade. A standardized “worth” to money enabled a transaction’s participants to easily assign a value to goods and services that eliminated the imprecision of on-the-spot bartering.

So adapting the prior farmer/tailor example, instead of having to equalize the transaction via a promise of later payment, the “inherent” value of the products can be instantaneously reflected in the medium of exchange: The farmer buys a pair of socks from the tailor for $10, and then — separately — sells him a block of cheese for $5. Two transactions, complete.

But now let’s presume that the farmer has neither cash nor a second block of cheese, yet still really needs those socks.

“That’s OK,” the tailor says. “Take the $10 socks now, give me your $5 block of cheese, and pay me the remaining $5 later. But for the luxury of paying me later, I’m going to charge you an extra $1 per month until you fully pay me.” The farmer happily obtains his socks, plus a debt — with interest.

That’s how the modern economy works. Soon enough — after a few such transactions — the farmer owes the tailor $28 trillion.

Now: Let’s examine America’s present-day $28 trillion global debt, because just as the farmer can’t possibly repay his debt, neither can America. And that compels the question of whether the tailor should have expected to be repaid in the first place.

The tailor likes cheese. Like, a lot. And although he wanted to be paid more than the farmer could give him at the time of the transaction, he was nonetheless willing to part with his handcrafted socks for less than their stated value. Sure, he bargained to be paid more later, he expected to be paid more later, yet he still nonetheless agreed to part with his socks in that moment for the price that the farmer could then pay.

At any time during their several subsequent exchanges, the tailor could have stopped trading pairs of wool socks for blocks of cheese — but his cheese habit compelled him to keep parting with his socks in exchange for whatever cheese the farmer could offer (plus that increasingly suspect promise to pay the balance later).

So: Was a pair of wool socks truly worth two blocks of cheese, given that the tailor was so consistently willing to part with them — in practice, in that moment — for only one block of cheese?

Unsurprisingly, the farmer eventually comes back and says, “Sorry T, turns out I’m destitute, and thus can’t give you all those second blocks of cheese I previously promised you.”

Whatever. The fact remains that, while the tailor had anticipated receiving the cheese he was rightfully owed, his belly had still been filled with that which had made parting with his socks worth it to him at the time.

Sure, had the tailor known he ultimately wouldn’t be paid the full amount of the debt, maybe he wouldn’t have sold the farmer his wool socks — but that would’ve meant forfeiting access to any cheese at all. And the tailor could not have abided such deprivation.

The reason I’m beating this wearied horse to death is to explain the significance of every single American’s $85,000 share of the national debt — a per-person obligation more than twice the United States median per capita annual income. (Incidentally, that $85K figure factors in all 330 million Americans, be they infants or your lazy deadbeat cousin who has no intention of working a single day his entire life. The share of the national debt for every adult taxpayer? A cool $909,000. Yup.)

Everybody knows America’s debt won’t be repaid, yet nobody seems to care. And the kicker is that it doesn’t matter anyway.

That’s because the myriad transactions that accounted for our present obligation to repay a preposterous number of zeroes were incorrectly valued in the first place. That $28 trillion debt is the outstanding legacy of countless exchanges that already happened.

Two parties to a deal were sufficiently satisfied with their bargain to finalize negotiations and go on their merry ways. Yes, one of those parties foolishly believed she would eventually receive the unpaid balance, in addition to interest payments in the interim. But as the balance sheet shows, that expectation was wrong.

One day the tailor says to the farmer, “If you don’t pay me the blocks of cheese you owe me, I’ll not sell you any more wool socks.”

The farmer — looking sheepish but nonetheless secure in the true dynamic undergirding their negotiations — merely shrugs, and says softly: “But if you don’t give me more socks, my feet will be too cold to make you any cheese at all.”

Thus, the essential truth: Though the tailor is owed several trillion blocks of cheese, he’d rather have one more block than no more. The terms of the transaction were wrong from the jump.

The tailor had valued his time, labor, and the cost of raw materials to arrive at a price-per-sock-pair that was twice the cost of a block of cheese, but had overlooked one simple criterion that he hadn’t priced into his socks: to wit, that he really, really likes cheese.

So let’s finally kill off this horse (which, to keep things simple, belongs to an unrelated farmer).

America is the farmer, and the global financial system is the tailor too afraid to permit our fiscal default. Why? Because the worldwide financial system likes our cheese. It needs our cheese.

And though cheese is horrendously unhealthy in the quantities that the world consumes, we just can’t stop. That $28 trillion debt symbolizes the American empire. It’s the price tag of enforcing the integrity of a unified international market, a.k.a., “the cheese.”

Until the world’s creditors — be they China, international financial institutions, Social Security recipients, or domestic mutual fund managers pile-driving money into allegedly safe U.S. Treasury-backed securities — wean themselves from our cheese, America will continue to expand its debt load. And a debt that won’t be repaid is just a meaningless string of zeros on a spreadsheet.

By the time the world declares that American cheese no longer has any value, the entire construct of money will be meaningless anyway — as portended by a recent article in “The Onion” entitled “U.S. Economy Grinds To Halt As Nation Realizes Money Just A Symbolic, Mutually Shared Illusion.”

So the next time you encounter someone shrieking about a $28 trillion national debt, voice some relaxed skepticism; explain that our debt doesn’t represent what the U.S. owes its creditors so much as it represents the intangible value of outsourcing to America the responsibility for shouldering an integrated global financial system — backed by the all-mighty American dollar.

(True: Reality does significantly depart from our hypothetical. Because when America stops by to inform the tailor that it can’t deliver all the cheese it owes but regardless still wants more wool socks, it brings along its nuclear arsenal and historical willingness to invade sovereign nations for the sport of it. But for the sake of this column, just shut up already.)

So Uncle Sam might as well keep borrowing money with fevered abandon — shorthand for “print more money,” which I presume entails some dude at the Treasury Department adjusting an Excel document with an extra “0” — while the Nations of Earth remain “involuntarily willing” to let us get away with it. At the end of the day, the real value of our debt is ZERO.

If the world community deigns to change the prevailing status quo — and actually takes responsibility for the excesses of war, environmental devastation, and wholesale socioeconomic inequality — then it need not demand that America repay its debts. Rather, the world (and all of us) must become less reliant on American cheese.

After all, the global economy wouldn’t tolerate America’s debts if it weren’t existentially dependent on the economic activity spurred by manufacturing socks in exchange for cheese.

Until then, Americans should probably keep one eye fixated on a future after the world wakes up — when our 401Ks are suddenly meaningless and issuing stimulus checks in a crisis is mathematically infeasible. Because last month, the Congressional Budget Office projected that America’s federal debt in 2021 would exceed the size of the entire U.S. economy (i.e., the gross domestic product — a measure of the country’s total goods and services). And someday, it’s at least plausible that two plus two will once again equal four.

I’m not saying that the global financial system will collapse but, if it doesn’t, then I guess we’re well on our way to finding out what number comes after “trillion.”

In the meantime, let’s just all keep pretending that money has value. Because although the emperor may be mostly naked, those sure are some snazzy wool socks.

Captain Jesse Sommer is an active duty Army paratrooper and lifelong resident of Albany County. He welcomes your thoughts at jesse@altamontenterprise.com.

The back-to-back traumas of 2021’s first month disabused any hope that the surreal horrors of last year would be neatly exiled to the safer confines of history. Less unique aberration than a preview of what lies ahead in our slog through millennia’s third decade, even 2020 would’ve been hard-pressed to predict the new year’s Capitol siege or a second presidential impeachment.

Our national politics are completely dysfunctional, the democratic system through which they’ve long been expressed has frayed beyond total disrepair, the stock market has been exposed as a precarious fraud for the 38 millionth time, and America has jumped the shark. This is the new normal. This is who we are. And I was apparently too engrossed by yet another paralyzing TikTok binge to notice the moment we rampaged past the point of no return.

Welcome to February. If tomorrow I’m accosted by a sentient killer robot newly escaped from some corporate R&D lab, my only question of it will be: “What took you so long?” Here’s my rundown of what January introduced:

— Do you even 25th Amendment, Bro?

Despite your willingness to wax eloquent on the 25th Amendment, we both know neither of us has actually read it. Gimme a sec — OK; just skimmed it. Turns out only its fourth section is germane to recent events, and there’s a gaping ambiguity in it: if the 25th Amendment were ever invoked, who would be commander-in-chief of the armed forces?

The provision details how the vice president would “assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President,” how the president then would “resume the powers and duties of his office,” and back-and-forth. But who’s in control of the military during this procedural chaos? Don’t presume it’s so straightforward.

Is it still the president, or does the vice president’s written declaration of the boss’s unsuitability somehow magically inject him/her into the chain of command as “acting” commander-in-chief, too? During such a tense period, which of these two can issue the lawful orders that the Defense Department is beholden to execute, and might carrying them out subject servicemembers to Nuremberg-style liability?

The relevance of this inquiry is accentuated by jaw-dropping public dicta in The Washington Post on Jan. 3, 2021, by the 10 living former defense secretaries who reminded uniformed personnel that their sacred oath of service is to the Constitution, not to an individual. The necessity of that unprecedented maneuver should horrify you.

— Despite architectural advancements, divided houses still cannot stand

I derive a perverse sense of pride from the fact that the gravest threat facing America is, well, Americans. Unable to dominate us militaristically, economically, culturally, or anything-ly, our most pernicious adversaries finally identified the weapon with which they could destroy us: ourselves.

Using made-in-America social media platforms and integrated network technologies, Russia spent half a decade sewing irreparable discord into the fabric of our national identity via fake news and incendiary partisan rhetoric while concurrently hacking its way into the deepest corners of our business and government sectors.

And we mindlessly swallowed the bait hook-line-and-sinker, retreating into ideological camps demarcated by pink pussy beanies on one side and red MAGA caps on the other. The enemy — gleefully incredulous as we sharpen our knives against each other — now whispers, “Divide and conquer” while we chant “U-S-A! U-S-A!” and crank out an unyielding torrent of progressively idiotic memes.

Are you equally as appalled by the self-assuredness of a citizen populace whose approach to developing opinions is constrained by whatever information fits in 140 characters? Yes, I’m talking about you.

And I’m talking about me — because I haven’t read a book cover-to-cover since 2006, yet I spend hours a week scrolling through news feeds before publishing a monthly column wherein I convince myself that I know what I’m talking about.

— Facial recognition and our digital pocket spies