A Prohibition tale of deception, wealth, explosion, and death

— Orange County Archives

Sheriff’s deputies dump illegal alcohol during a raid in Orange County California in 1932 while a trio of dour women watch. Prohibition in the United States began in 1920 when the 18th Amendment went into effect and was repealed in 1933 with the ratification of the 21st Amendment.

Feb. 1, 1927 found Robert and Joseph Battaglia in business as Battaglia Bros. Poultry Farm in a secluded spot on the portion of West Lydius Street between Carman Road and Church Road, in what is now the Fort Hunter area of Guilderland, raising chickens on acreage owned by a New York City in-law.

Approached that day by three men, one introducing himself as John Mitchell of Albany, and accompanied by a John Smith and a third man never identified, Robert Battaglia was offered a deal. Mitchell proposed to lease the farm’s unused 40-by-60-foot barn situated behind the chicken coops along with a small area of land around it, agreeing to pay a rental of $30 monthly.

The three men claimed to need a location where they would be “experimenting” to produce their product, which was to be “sauerkraut” (quotes in the original news story).

In the weeks ahead, under the cover of darkness, trucks drove in and out, with the doings in the barn cloaked in secrecy. Off limits to the Battaglias, the barn, where the doors were always barred, saw much activity.

John Mitchell and associates were actually creating an illegal, but very professional, high capacity still at great expense. Several huge copper vats, each capable of holding several hundred gallons of alcohol were carried in, in pieces, to be reassembled inside. A huge steam boiler was set up as part of the operation.

In the midst of the nation’s futile attempt at Prohibition, gangsters were producing huge quantities of illegal alcohol in stills frequently situated in isolated rural areas. The Battaglia farm was the perfect site off a rarely traveled dirt country road, yet easily accessible to Albany via Carman Road to Route 20 or to Schenectady via Church Road/Helderberg Avenue.

The gangsters of that era were ruthless (think Legs Diamond or Dutch Schultz and their hit men), and the men involved in setting up this still were definitely professional criminals. The Battaglias were probably well aware of what was unfolding on their farm, but wouldn’t have seen, heard, or known anything if they wanted to remain healthy.

Under the Volstead Act, the nation’s Prohibition statute passed by Congress in 1919, property could be confiscated if illegal alcohol was being made or sold there. Perhaps it was this knowledge that may have motivated Robert Battaglia to demand that John Mitchell buy the barn and four acres surrounding it.

After getting permission from his New York City relatives to sell the property, on Feb. 16 Mitchell paid Battaglia $500 down and agreed to a $2,500 mortgage held by Battaglia. Schenectady Attorney Hannibal Pardi handled the legal details. Mitchell then “disappeared.”

Explosion

Around noon on March 10, Joseph Battaglia was tossing feed to a flock of clucking hens. He later claimed that, due to the sounds of the chickens, he was barely aware of an explosion out back by the barn or the sounds of men calling out in excruciating pain. He claimed it was some time before he realized something was amiss.

Several yards behind the hen house, the explosion in the barn was shortly followed by a second blast and a fiery inferno. After the first blast, a man came staggering out of the barn, his clothes afire. As he threw himself into snow remaining on the ground, another man rushed to his aid, only to be knocked down, his clothes in flames from the second blast. A third man also suffered burns but not so extensively.

The two critically burned men were placed in a Chevrolet touring car, sped to Ellis Hospital, and dropped off at the dispensary door with no explanation to hospital staff. The driver hurried away before he could be questioned.

The third victim was supposedly driven to Kingston for treatment, but it was also possible he was taken to a Schenectady doctor on State Street. Accounts differed.

Conscious in spite of their terrible injuries, the two men, when questioned, refused to identify themselves, giving conflicting accounts of how they acquired such severe burns. When it became obvious that one was about to die, the coroner was called in an attempt to get information. Finally, the dying man admitted to being John Smith, rooming at 405 Union Street in Schenectady.

With difficulty, the undersheriff and accompanying newsmen found the location of the blast. Parked by the charred ruins was the dead man’s Chevrolet touring car.

Identities revealed

Tracing the license plate revealed John Smith was actually a bootlegger named Carmen Tuosto from Rome, New York, out on $5,000 bail after having been indicted by a federal grand jury in Rome in January. An experienced still operator, Tuosto ran a still near Rome worth $100,000, capable of producing $15,000 worth of liquor weekly.

Tuosto’s family refused to give authorities any additional information, only requesting that his body be shipped back for burial.

After examining the fire scene, Undersheriff Lopen estimated the Guilderland still’s potential capacity would have been 1,750 gallons with each vat holding 250 gallons. The value of the still itself would have been $20,000. Several five-gallon gasoline cans and a large steam engine were visible in the barn’s charred ruins.

The second severely burned man turned out to be Dominick Frederick, a contractor living at 107 Foster Avenue in Schenectady, who told authorities he visited the Battaglia farm several times weekly to buy a couple of dozen eggs.

He just happened to be there when the blast occurred, rushing over to help the unfortunate burn victim writhing in agony in the snow when he, too was set on fire by the second blast. His death at Ellis was reported three days after the blast and fire.

“THIRD MAN IN RUM STILL BLOWUP HELD” read a huge banner headline across the front page of the April 1 edition of the Schenectady Union-Star, while a slightly smaller two-column headline below informed readers, “Say Jack Rocco Owned Big Plant in Guilderland.”

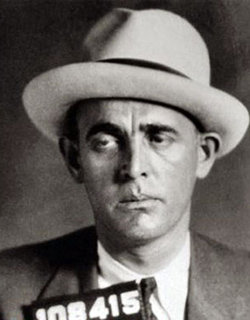

Claiming that authorities were certain John Mitchell was an alias used by Jack Della Rocco, also known as Jack Della, the lengthy article added that Della Rocco had been arrested on a warrant from the Albany District Prohibition Office.

Two days later, he was arraigned before United States Commissioner Charles E. Parker and charged with the manufacture of illicit beverages, a violation of the Volstead Act. Della Rocco was released on $2,500 bail.

Della Rocco, who was less seriously burned in the March 10 still explosion, was rumored to have either been driven to Kingston for treatment or taken to a doctor in Schenectady after the other two were left at Ellis.

Certainly in April, he was in Schenectady under the care of Dr. Fred McDonald, who convinced authorities to delay arresting Della Rocco until his burns healed. Before the explosion, he had been rooming with a family on Ingersoll Avenue in Schenectady.

Only at this time did the identity of the mystery driver who had left the two fatally burned men at Ellis become known. He was Fred Adams, described as a neighbor of the Battaglias. Adams refused to make any further comments.

Courts and coverage

Police and Prohibition officers searched extensively for John Mitchell, finally coming to the conclusion Mitchell and Della Rocco were the same man. Unfortunately any witnesses who could verify the suspicion either were dead or weren’t talking.

Robert Battaglia denied that they were the same man, having begun a legal process to foreclose on Mitchell’s title to the four acres he had purchased in February.

An announcement made by the Albany District Prohibition chief stated the federal grand jury might consider the case of Jack Della Rocco. United States Commissioner Parker conducted a hearing, but reserved his decision.

Even if indicted, Della Rocco’s conviction would seem unlikely with key witnesses unwilling to testify against him. Government officials attempting to enforce the Volstead Act were rarely successful in obtaining guilty verdicts.Silence, evasion, inconsistencies, lies, witness tampering or threats; all of these prevented convictions during Prohibition years.

This Guilderland Prohibition tale was pieced together from the many articles in the Schenectady newspapers, both the Union-Star and the Gazette. Heavy coverage was likely because all three men were living in Schenectady and because in 1927 these papers seemed to be regularly carrying news from the area of western Guilderland including Altamont and Guilderland Center.

Even though the explosion occurred in Albany County, the Albany Times-Union didn’t cover it and the Knickerbocker Press’s coverage was minimal. Nothing about this incident appeared in The Altamont Enterprise.

A postscript to this tale appeared in a Nov. 15, 2015 Schenectady Gazette feature article “The Bootlegger’s Daughter.” Centenarian Agnes Frederick Tripolo, Dominic Frederick’s daughter, shared her memories of her Schenectady childhood in the 1920s.

Her father, born in Italy as Domenico Frederico, later anglicized his name to Dominick Frederick. Agnes remembered that he had a still in Guilderland, bringing home the distilled liquor to be stored in a secure place in the cellar of their Foster Avenue home. He then made deliveries to local taverns operating speakeasies. He drove one of his Studebakers, often taking his daughter or wife along to make it seem like a normal drive.

As she reminisced with reporter Karen Bjornland, Mrs. Tripolo said it wasn’t unusual for the mayor, policemen, and musicians to share a meal at their home. Dominick Frederic prospered until the explosion brought his successful bootlegging operation and his life to an end.

In an email to the Gazette reporter, Dominick Frederick’s grandson Joseph Tripolo offered his opinion: “My take on it all was his death and his operation, a million dollar still, was wanted out of the way by some unsavory types trying to control market share.” And that was very likely the real story.