Guilderland’s name as well was some of its churches and buildings is rooted in its now nearly forgotten Dutch heritage

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

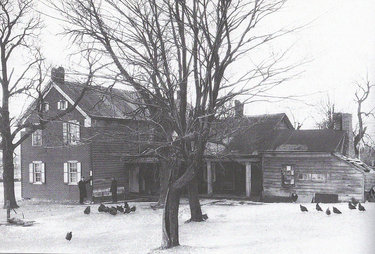

This photo of the rear of the Freeman House was taken as part of the 1930s Historic American Buildings Survey. The original Dutch door remains on the front and the house has been carefully preserved. Once a Dutch barn stood nearby, but it burned in the early 20th Century.

Contemporary Guilderland’s familiar landscape is for the most part suburban developments, strip malls, shopping centers, paved roads and parking lots, and apartment complexes. From our vantage point in time, it’s almost impossible to visualize our hometown 200 or 250 years ago, covered in virgin forest or pine bush, broken here and there by streams and swamps.

Once part of New Netherland, the colony established along the Hudson in the early 1600s by the Dutch West India Company, the area was taken over by the English in 1664 and renamed New York.

Evert Bancker of Albany, reputed to be the town’s earliest settler traveled up the Normanskill by canoe, establishing a farm in the area near today’s Tawasentha Park. Followed by other Dutch settlers and a few Germans, farms began to be scattered about in what is now Guilderland. All were tenants on the West Manor of Rensselaerwyck, expected to pay an annual rent in crops to the Van Rensselaer family.

While it is difficult to picture Guilderland’s physical surroundings in the 18th Century, the people themselves are so distant from us as to challenge our imagination. Looking back to this period, what can we reconstruct of the lives of these early settlers?

Worship

Dutch and German were their first languages and their early church records were in those languages. Dutch settlers, members of the Dutch Reformed religion, and German settlers, adherents of the Lutheran religion, were each visited sporadically by circuit-riding ministers. The Dutch Reformed Church had its formal beginnings in 1767 when the first church building was erected, but even earlier there had been a log meeting house used. Services were in Dutch until 1788 and their written records were kept in Dutch until 1796.

St. James Lutheran Church officially began as St. Jacobus in 1787 by the town’s German settlers with the erection of a small church building. Within a few years, the name was anglicized to St. James. Previously, when the minister came to our area, he held services in local homes. Pastor Sommer noted (the original in German) in August 1762, “I preached below the Helleberg in Michael Friederichs’s house and administered the Lord’s Supper.”

The earliest written records from St. James were in German as well. An indenture written for Patroon Stephen Van Rensselaer with the Minister and Deacons of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of the Helleberg mentions Low Dutch and German language services.

Houses

Although some of the early settlers here were German, they originated in that part of Germany that is adjacent to the Netherlands, and shared much material culture. Few of their early homes survive in Guilderland, unlike some other areas in the Hudson Valley, but fortunately a few photographs survive showing the Dutch influence on one early farmhouse.

Built of locally made brick and laid in the traditional Dutch style, a house photographed in the 1930s has been covered with stucco, but a later picture shows the stucco removed and the bricks clearly showing. Possibly built around 1700, it is the oldest house in Guilderland. But, since the 1930s photograph, owners did extensive remodeling, changing the character of the house.

Another early Dutch house was the Wemple house, taken down when Watervliet Reservoir flooded its location.

The oldest frame house in town is the Freeman House in Guilderland Center, reputed to have been built in 1734. In a 1966 interview, Mrs. Robert Davis, who with her husband were then owners of the house, mentioned the original Dutch door and that they had uncovered Delft tiles in the fireplace when they uncovered it. The Dutch typically had jambless fireplaces, having no mantel or sides, decorated with Dutch tiles.

A 1930s photo showed that the house still had its front stoop, another characteristic of Dutch houses.

The gambrel roofs on two of them reflect English influence, however. It’s possible there are other old houses in Guilderland that have some evidence of Dutch influence, but it has often been obliterated by later additions or remodeling.

Barns

Beginning with Evert Bancker, farmers needed barns to store crops and keep their animals. Early farmhouses were small, but nearby there would have been a large Dutch barn, the predominant barn style in our area as late as the 1820s.

These barns had a framework of beams that was a series of H’s supporting the roof. No nails were used, only wooden pegs. At the gable ends were wide doors to allow wagons to enter and exit. Small doors on each side of the front corners let animals in and out.

The side walls were low and the barn had a boxy shape. At the gable peak were holes called martin holes to allow swallows to fly in and out.

In the interior, a wide center aisle ran the length of the Dutch barn, a space where wagons could be unloaded and grain could be threshed using a flail or with horses dragging a length of wood over the wheat in a circular direction. On each side of the center aisle was a space for equipment storage or to house livestock. By laying saplings across the beams, farmers could lay sheaves of grain or hay for storage.

These barns were extremely well built using the virgin timber available at that time and, if maintained, have lasted until the present day, including several in the town of Guilderland.

Near the barn would have been a hay barrack, a structure with five upright poles and a roof that could be raised and lowered depending on the amount of hay to be stored and kept dry. This storage method was typical in the Netherlands and was copied over here, often being mentioned in descriptions by travelers.

Swedish naturalist Peter Kalm traveled through the Albany area in 1748, mentioning that everywhere he could see that type of “haystacks with moveable roofs.”

Farming

Mixed farming was the rule, with wheat the predominant crop needed to pay rent to Van Rensselaer for the farm. In addition to wheat, farmers raised garden produce, herbs, fruit, corn, oats, “pease,” and barley.

Kalm noted that around Albany local farmers could produce from 12 to 20 bushels of wheat from sowing one bushel. Every farm had livestock: horses, cows, sheep, chickens, geese, and pigs.

Dutch farms had definite differences from the English type of farm in New England. Grain and hay were cut by swinging a sith or scythe with a short handle in one hand and, holding a mathook in the other, supporting the crop upright to make it easy to cut. The farmer did not have to bend as low as he would have with an English-style sickle and, as a result, could harvest an acre in a day, two or three times as much as he could have with an English sickle.

Dutch wagons were also unique, having rear wheels larger than the front wheels. The front board was larger than the rear and spindles ran along the sides.

Dutch plows were also different from English plows, having a pyramidal plowshare, one handle and two wheels. Another observer visiting the Albany area in 1769 wrote that farmers “used wheeled plows mostly with 3 horses abreast & plow and harrow sometimes on a full trot, a boy sitting on one horse.”

Is there any evidence that this material culture was typical of Guilderland’s early farmers? In 1813, when George Severson, the proprietor of the Wayside Tavern on the “Schohary” Road (located where the Stewart’s Shop in Altamont’s is located today) and a farmer of the land surrounding his tavern died, an extensive inventory was taken of all his possessions and farm equipment.

A lumber wagon worth $40 and a pleasure wagon valued at $30 are listed, though there is no way of knowing whether either of them was a Dutch-style wagon. There is listed, however, one wheeled plow worth $10. Ten sythes are listed for $5 and three sythesnaths for $1.50, these being handles for the sythes, as well as two small hooks valued at 25 cents.

Also included was a skipple measure, this being a Dutch measure used instead of an English bushel. Since he also had half-bushel and peck measures, perhaps the skipple measure was no longer used by 1813.

Also listed were horses, sheep, cows, hogs, fowls, and geese along with two bee hives. Severson raised a variety of crops with amounts of wheat, oats, pease, flax, barley, hay on hand, and must have had an apple orchard since a “cyder” press was among his possessions.

Enslaved people

Dutch settlers had no qualms about owning enslaved people. Slaves had been brought into the Colony of New Netherland by the mid-1600s and the custom of slave ownership spread throughout the colony, continuing after the English takeover in 1664.

Sadly, in the midst of George Severson’s inventory of his possessions were two enslaved women who were sold at auction for $191. In 1810, the census showed that there were 66 slaves in Guilderland while in 1820 the number had dropped slightly to 47.

Certainly not every Guilderland family owned one or more slaves, but the 1810 and 1820 census records recorded which families did, how many and their ages. Finally, in 1827, New York State emancipated slaves within the state.

Fading Dutch culture

Gradually, by 1800, the Dutch culture had slowly faded, but it’s still possible to find bits of our Dutch heritage with place names such as Bozenkill, Normanskill, and Hungerkill, which still continue to be used. However, at some point, the Schwartzkill was anglicized to Black Creek.

When the town government was formed in 1803, it was given the name of Guilderland after Gelderland, the Dutch province that was the original home of the Van Rensselaer family. Old families anglicized their names: Oxburgers became Ogsburys, Friederichs became Fredericks, and Crans or Cranse or Crounce became Crounse.

The Helderberg Reformed and Altamont Reformed churches are direct heirs of the original Dutch Reformed Church while St. John’s Lutheran Church originated in St. James Lutheran Church.

A few of our town’s Dutch barns have survived to the present day, though sadly all too many have disappeared due to neglect or fire. When a 1947 wildfire that threatened the hamlet of Guilderland Center destroyed the orchards of Edward Griffith, wiping out his livelihood, he talked sadly about his great loss — his barn, which he said was historically valuable, dating from the 1700s, constructed of hand-hewn timbers with wooden pegs and its original doors.

Other Dutch barns have been removed to be re-erected elsewhere. The 200-year-old Ogsbury barn from just outside of Guilderland Center was taken apart in 1982 and moved to the Philipsburg Manor historic site in Westchester County to replace another Dutch barn that burned.

Fortunately, the Dutch Barn Society has been working since 1985 to record existing Dutch barns and to encourage their preservation in the areas of Dutch-German settlement.

While some residents in our town can claim to have had Dutch or German ancestors from among our town’s earliest settlers, sadly most modern-day residents are unaware of the town’s Dutch beginnings or even that the name Guilderland comes from a Dutch province.