‘What we can’t understand we call nonsense’

For Jimmy Kimmel

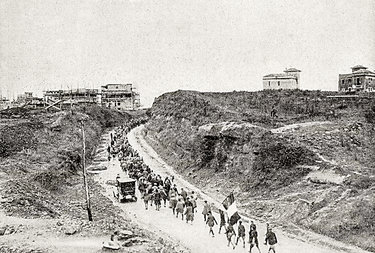

On Oct. 28, 1922, more than 30,000 black-shirted paramilitary fascists — the Italian word is squadristi — under the leadership of Benito Mussolini marched into Rome to take control of the capital of the Italian nation.

Historians refer to the insurrection as “The March on Rome,” which seems to have been a harbinger of the mob attacking the Capitol of the United States on Jan. 6, 2021.

Two days after the take-over, the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III — with the support of the social elites of the nation, the corporate world, and the military — ceded power to Mussolini. On Halloween, the dictator formed a government that soon became the one-man-rule of il duce.

In her profile of Signore Dux, in “Fascist Spectacle: The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini’s Italy,” cultural sociologist Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi says the dictator saw himself as “God’s elect;” a “savior;” a homo unus — the one and only who could help Rome be great again.

Was that not a harbinger as well of what was broadcast across the United States in 2016 when the country’s current president said he was going to save America because “I alone can fix it;” and in November of the following year, when the cult personality of homo unus was solidified, added: “I’m the only one that matters.”

After taking control of the capital — Italy’s legislators having folded like a house of cards — Mussolini turned to his propaganda tsar, the “philosopher of fascism,” Giovanni Gentile — officially the Minister of Public Education — and ordered him to soak every Italian kid in every school in the nation with the hose of fascist doctrine.

He wanted under his control every Italian kid when he turned 6 until he reached 16, because he knew, by then their veins were plump with totalitarian Newspeak.

Gentile’s treatise “Manifesto degli Intellettuali del Fascismo” “The Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals,” served as a blueprint for the political and ideological underpinnings of Italian fascism. The idea was to get control of the big minds, the smart guys, and have them work on the hoi polloi below.

The work is a justificatory rationalization for the black-shirted guards of the National Fascist Party (PNF) using violence against those who refuse to submit to psychological debasement.

In a section called “Fascism and the State,” Gentile reminds the reader that a “victorious Nation was now on the path to recovering its financial and moral integrity” and by “recovering” he meant MRGA “Make Rome Great Again.”

In no time, the curricula in schools were ablaze with fascist lingo. British writer Anthony Rhodes, in “Propaganda: the art of persuasion, World War II” (Wellfleet Press, 1987) says, “very soon, at least 20 percent of the curriculum in the elementary schools had been revised in this sense, teaching the adolescent from very early days his duties as a Fascist citizen.”

When the school-day started, the kids joined in on the “Giovinezza,” the national anthem of the Italian National Fascist Party, the PNF, Partito Nazionale Fascista.

Its refrain is:

Youth, youth,

Spring of beauty,

In Fascism is the salvation

Of our freedom.

At the university level, students were “urged” to join Gruppi Universitari Fascista, if they hoped to get somewhere in life. ¿Entiende?

As the totalitarian disease spread across the nation, the citizenry were forced to retreat to their minds for emotional support—as Orwell says people did in “Nineteen Eighty-Four”—and as many Americans in the United States are doing today for psychological relief.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a movie is worth a million and no director has put more millions on the big screen addressing the insanity of fascism than Federico Fellini.

He hits its coercive socialization in the face in “Amarcord,” his big-screen portrayal of him growing up in Rimini, a small town on the Adriatic coast.

Amarcord is dialect from the Romagna region where Rimini is located and means “I Remember.”

Thus, every frame of the memoir-driven jewel has the maestro shooting off Roman-candle images of every kind of person you can imagine living in a small town in 1930s Italy.

Fellini told potential viewers to keep their eyes peeled for the part when a fascist government official, a federale, comes to town and rouses the locals to march like soldiers in double-time-step and sing songs honoring the very power enslaving them; he said the scene is “the central, irreplaceable, indispensable episode” of the movie.

The artistic genius of “Amarcord” was duly acknowledged by the film world by being awarded the 1973 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. It’s on the top-10 list of untold thousands — cineastes and otherwise — and close to the top of mine.

Though the film is filled with humor and an irony that reaches the heart, there’s sadness in seeing Rimini’s pedagogues, the Latin, Theology, and Science teacher at the local school — practitioners of the old-time rote method of learning, unaware of the lives of the young men before them — donning black shirts and pants and goose-stepping boots to show the federale how much they loved kissing the emperor’s ass.

For more than a decade I’ve told members of my memoir-writing group at the Voorheesville Public Library to view “Amarcord” and use it as a rod to measure how well they extricate truth from the past and put it down on paper with clarity. So far, all I’ve heard is crickets.

Mussolini encouraged acts of intimidation, ordered beatings and the breaking of bones, even murders. Anyone who blinked the wrong way, they said, was subject to the manganello (the billy club) and castor oil.

Castor oil? As “Amarcord” progresses, the black shirts drag a local into headquarters for questioning — an older family-man, a brick-layer-cum-foreman — and accuse him of having thoughts contrary to the regime.

To force the sorry soul to come clean — no pun intended in any way — they force castor oil down his throat, a personally-denigrating torture Mussolini’s black-shirted employees used to embarrass infidels by causing them to lose control of bodily functions.

Remember: Castor oil is a powerful laxative.

Thus our oil-soaked brick-layer-cum-foreman didn’t get past the front door before messing his pants and suffering the humiliation the fascists sought to achieve.

It was the [crazy] Italian poet Gabriele D'Annunzio who introduced the regime to castor oil, as well as to the fascist salute, and black shirts, and balcony speeches, and other forms of drama made to force the ethically insecure to cave. Some say D'Annunzio was Mussolini’s John the Baptist.

Fellini said understanding fascism was no big thing: it derives from “a provincial spirit, a lack of knowledge of real problems and the rejection of people, whether out of laziness, prejudice, greed or ignorance, to give their lives a deeper meaning.”

He said “Fascism and adolescence … [were] permanent historical phases of our lives. Adolescence is of our individual lives; Fascism is of the national life: [the desire] to remain, in short, eternal children.” Pueri aeterni.

No matter what level one has reached in knowing the basics of history, no one has not heard of the saying: When we fail to pay attention to the evil our forebears did, we pay double because we repeat the same evil by becoming it incarnate.

The Oregon-based American novelist Chuck Palahniuk has rued, “If you watch close, history does nothing but repeat itself. What we call chaos is just patterns we haven't recognized. What we call random is just patterns we can’t decipher. What we can’t understand we call nonsense. What we can’t read we call gibberish. There is no free will.”

To translate such dystopian talk, I turn to our beloved national treasure, Mr. Pete Seeger — blacklisted for espousing beliefs under another regime — in his 1955 American classic “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”

In the somber tone of a Greek chorus he inquires:

When will you ever learn?

When will you ever learn?