Carlin, a disappointed idealist turned cynic, poured salt on America’s wounds

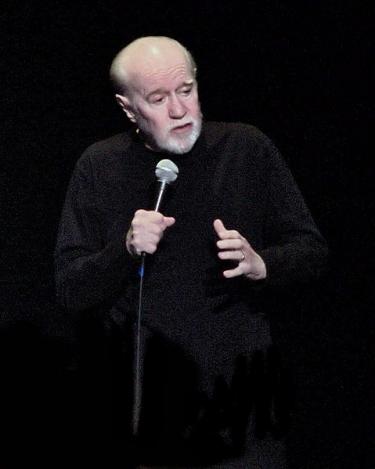

George Carlin is the greatest comedian of all time. Some “best of” lists put Pryor first and Carlin next but others say Carlin is a league all his own.

Jon Stewart may have solved the problem in 1997 when he introduced Carlin during the comic’s 10th HBO special “George Carlin: 40 Years of Comedy” as one of the “holy trinity” of comedy: Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, and George Carlin.

Carlin traced his roots to Bruce and, before Bruce, to Mort Sahl, a lineage of social critics who, through the millennia, called Aristophanes, the “Father of Comedy,” the seed of their comedic work. It was a bloodline that did not suffer Borscht Belt mother-in-law, two-guys-walk-into-a-bar, and lost-airline-luggage jokes.

While Carlin started out with a suit-and-tie Vegas act, when the Sixties rolled around, a beard appeared and his hair fell to his shoulders. He painted iconic characters like Al Sleet, the “Hippy Dippy Weatherman.” Fans recall with delight Al’s: “Tonight’s forecast: Dark. Continued dark tonight, turning to partly light in the morning.”

It seems from the beginning Carlin was piqued by people’s disabuse of language through mystifications, masked contradictions, and linguistic absurdities. While he could garner a laugh from his oxymoronic “jumbo shrimp” and “military intelligence” bits, his true interest lay in sustaining an attack on those who devalued the gift of language by using it to obfuscate reality.

In a classic bit on euphemisms he said: “I don’t like words that hide the truth. I don’t like words that conceal reality. I don’t like euphemisms, or euphemistic language. And American English is loaded with euphemisms. ’Cause Americans have a lot of trouble dealing with reality. Americans have trouble facing the truth, so they invent the kind of a soft language to protect themselves from it, and it gets worse with every generation.”

Those familiar with comedy know Carlin was arrested at Summerfest in Milwaukee in July 1972 for saying the “Seven Words you Can Never Say on Television.”

It was a bit he introduced on his best-selling album “Class Clown” two months earlier. “There are 400,000 words in the English language,” he began, “but only seven of them that you can’t say on television. What a ratio that is! 399,993 to 7. They must really be bad.”

You can see why Carlin remained an “outside dog,” as Mort Sahl would say. In the preface to his 2004 “When Will Jesus Bring the Chops?” Carlin revealed: “I’m an outsider by choice, but not truly. It’s the unpleasantness of the system that keeps me out. I’d rather be in, in a good system. That’s where my discontent comes from: being forced to choose to stay outside.”

In each of his 14 HBO specials, the first aired in ’77, he hammered away minute by minute at the shaky myths the human community creates and submits to thereby limiting its chances for achieving well-being. He spoke about the “American Okie Doke” with its pithy equivocations: “all men are equal;” “justice is blind;” “the press is free;” “your vote counts;” “the police are on your side;” “the good guys win.”

He also went after the duplicities of religion, spoliative parenting, the hubris of prayer, demeaning education, illness-producing health, the glorification of the military, and a pandering self-help movement. He made his fans laugh but he pounded out his points with such vehemence that anyone who went to see him live had to take a day or two off to let the mental dust settle.

In many respects, Carlin was a Socratic prizefighter faulting the Athens of his day, the hoi polloi, for submitting to the demands of the powerful and for settling for a robopathic existence energized by consuming the packaged goods the market sells as indispensable for survival. He blurted that the gods of nature were on their way to strip this planet of sentience.

One group he especially liked to buzz were helicopter parents, the familial wardens who hover over their kids to insure they grow up to be disciplinized, docilized consumers of packaged realities.

Thus for kids he said, “The simple act of playing has been taken away ... and put on mommy’s schedule in the form of ‘play dates.’ Something that should be spontaneous and free is now being rigidly planned. When does a kid ever get to sit in the yard with a stick anymore?” And maybe dig a hole with it. He said that.

The stick is a metaphor for the imagination of course, kids not being given time to think and muse, and sometimes peer at the sky on a summer day to wonder how it all came to be.

Carlin well understood his professional development. Playing off a paradigm of Arthur Koestler on creativity, he acknowledged that he started out as a jester, comedy’s bottom-rung.

But, he added, when he began to follow ideas to their logical conclusion, he turned into a jester-philosopher; his routines changed. He said after that, because of his love for language, he reached the pinnacle of comedic art: the philosopher-poet.

The unending flow of his HBO specials forced the philosopher-poet to become a writer; he said they made him a writer-performer. And, if someone failed to acknowledge the writing as central, he’d set the record straight straightaway.

And it became clear that, the more America sold out her dream of equality and justice, the darker Carlin’s comedy got, very dark, in fact fading to black in his final HBO Special “It’s Bad for Ya.” He said the human race could blow itself up for all he cared; the planet would survive.

Over time, Carlin’s fancy for drugs forced him (in 2004) to go somewhere to get unhooked. On the road nearly every week of his adult life, he struggled with being a good husband and father. In “Conversations with Carlin: An In-Depth Discussion with George Carlin about Life, Sex, Death, Drugs, Comedy, Words, and so much more”, published in 2013, Larry Getlen presents a man who speaks about every aspect of his life with disarming honesty.

Carlin made million-seller comedy albums, he hosted the first “Saturday Night Live,” he wrote funny books, and in 2008 was posthumously awarded the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, I believe for being a great American.

Next month, that great American will be dead 10 years; I hope he’s doing well. Let us know if you run into him. The sad thing is: No one’s picked up the mantle of philosopher-poet.

The Australian-born but Americanized comic Jim Jefferies comes closest. Popular wits like Louis C. K., Amy Schumer, and Kevin Hart and a host of similars remain as distant from Carlin’s soul as Myron Cohen was 70 years ago. Even Chris Rock misses the boat.

As Carlin poured salt on America’s wounds he was the first to admit “Scratch any cynic and you will find a disappointed idealist.” And if he had had, like the comic legend Bob Hope, a theme song, it would have been “America the Beautiful” and Carlin would have pointed to the line “God mend thine every flaw” and say that was not God’s job but his.