Local mills ground grains into flour or meal to feed farm families and their animals

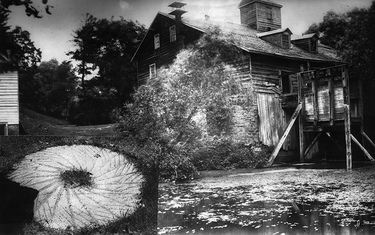

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

This photograph of Batterman’s Mill seems to be taken from the rear. In the lower left is an insert photo of a mill grindstone that could have actually been used in that mill. Note the groves in the mill stone, which would have required annual dressing to keep them functioning properly. This would have been one of two, one on top of the other to do the grinding.

At frequent intervals along Guilderland’s main roads, gas stations appear — not striking architecture but they serve a useful, necessary purpose for those who continue to drive cars with combustion engines. The same could be said of 19th-century grist mills, not particularly impressive, but necessary in their day to serve Guilderland’s large farm population if families, animals, and fowl were to be fed for the year ahead.

In 1845, for the first time, New York State conducted a state census, not only of population, but agricultural statistics as well as business information. At that time, Guilderland had two grist mills.

One was the Globe Mill on the Normanskill at Frenchs Hollow and the other was Batterman’s Mill on the Hungerkill in Guilderland where the stream was crossed by the Western Turnpike. Both mills operated by water power. Decades later, in the 19th Century, they were joined by a third mill in Altamont powered by steam.

In about the year 1800, coinciding with the opening of the Great Western Turnpike, George Batterman leased sizable acreage from the Van Rensselaer interests. He dammed the east and west branches of the Hungerkill where they joined together to create a large mill pond on the north side of the turnpike.

A sluice to carry the water ran under the turnpike to power the large mill opposite on the south side of the road. His mill combined the functions of a grist mill, plaster mill, and satinet factory to manufacture a cloth combining wool and cotton thread.

The mill was finally taken down in 1899 and its last year of operation isn’t known. Today, the level of Route 20 has been raised many feet higher than it was in the early 1800s and the sizable mill pond is now silted in, making it difficult to imagine the original mill site.

During the last years of the 18th Century, the rushing waters of the Normanskill at Frenchs Hollow were dammed and water was sent through a pipe into the mill to turn the water wheel, reputed to be 24 feet high although it’s possible that this early mill wasn’t as large as the mill had become in its later years.

The dimension of the mill wheel was cited in a 1932 article appearing in the Knickerbocker News, perhaps using as the source someone who could still remember the old mill in operation. This was also a dual-purpose mill with woolen cloth produced during the off season when there were no grains to mill.

At some point during the 19th Century, Elijah Spawn took over the mill and operated it with his son until the end of that century when he leased it out. On the 1854 Gould Map of Albany County showing Guilderland in detail, the site is marked Globe Mill, but a few years later, on the 1866 Beers Map, it is marked E. Spawn.

In 1896, Spawn leased the mill to Wesley Fuller, and it is not clear when the mill last operated. The property itself remained in Spawn hands until 1915 when the Watervliet Reservoir was being established.

The 1854 Gould Map also shows Normanvale Mills on the Hungerkill near where it flows into the Normanskill. Although the New York State 1845 Census mentions that only two grist mills operated in town, it’s possible these were just saw mills at this location also. The 1866 Beers Map shows only a saw mill here.

Few details of mill operation in Guilderland in the early decades of the 19th Century are known but, as Guilderland was a rural farming community, and of necessity families had to be self-sufficient in that era, the grist mills must have been very busy at harvest time, grinding grains into flour or meal to feed farm families and to produce feed for their animals and fowl.

Late 1800s

The later years of the 19th Century are more thoroughly documented. Once The Enterprise began publishing in 1884, it became possible to get some closer glimpses of Guilderland’s mill operation.

In Altamont, Adam Sand began operating a steam-powered grist mill, probably in the 1870s or early 1880s with his sons. In 1885, they announced they were ready to resume business after having completed repairs on their steam mill.

The next year, they let readers of The Enterprise know that they had acquired a corn sheller that would remove corn from the cob at no charge. Tragically, Adam Sand was killed in 1890 by an exploding mill stone.

A year later, his sons expanded their mill and then, in 1895, they erected a new building at Park Street and Fairview Avenue. A year later, the mill was sold to John H. Ottman who ran the mill until his death in 1905 when Miles Hayes took over, running the mill until it burned in 1928.

By the late 1800s, large-scale wheat-growing and milling had moved to the Midwest, but the local mills continued to have much business grinding rye, oats, corn, and buckwheat grown on the town’s farms until the early 20th Century.

“The grist mill of E. Spawn & Son is running day and night in order to grind the pancake timber,” that being buckwheat. “The crop is reported huge, flour selling at $2.25,” wrote the Enterprise Fullers columnist in October 1884.

A few years later, Spawn’s mill was doing a “lively business running day and night.” The same was said of Sands & Sons Mill, running day and night several different Octobers, which seemed to be the mills’ busiest time, both mills producing “pancake timber,” the local term for buckwheat flour.

Buckwheat was a very important local crop and breakfast staple of that day, and by the late 19th Century, the single most important output of the two mills. Buckwheat, a crop brought in by the Dutch in the 1600s, was easy to grow, a prolific producer even in poor soil, and very nutritious. It was widely grown in this area.

Economics

Mill owners earned their profits from either being paid in cash or in a percentage of the grain being milled, which they then resold. Spawn advertised that his standard horse feed was available for sale at several local general stores such as P. Petinger’s in Guilderland Center and Van Allen & Quackenbush in Fullers.

At the same time, he offered to pay for buckwheat and flour ground at his mill temporarily and advertised they would do custom feed grinding “for either cash or toll.”

Mills required maintenance to continue. It was noted at various times that both Spawn’s mill and Sands/Ottman mill were doing maintenance on their mills and would close down for a few weeks in the off season.

Mill stones required someone to “dress” them by having the grooves recut to allow the grain to be ground properly. It was noted at the death of John Batterman, the last Batterman owner of the family mill, that his mill hadn’t been brought up to date with the changes in milling, leading to a premature end to its operation.

John Batterman, owner of the Batterman’s mill for several decades, had been a very prosperous businessman, running his mill and operating a feed store in Albany, even serving as a trustee of Albany City Savings Institution.

By the 1890s, he had fallen on such hard times that his mill was sold at foreclosure for $5,500 in 1892. A year later, he was arrested after being caught red handed in Foundry owner Jay Newberry’s barn pilfering oats. He ended his days in the Albany Home for Aged Men, dying in 1902.

The author of the Enterprise’s “Guilderland” column sadly marked the 1899 demolition with a nostalgic final farewell: “Adieu, Thou was once so great and powerful and that hath prepared the staff of life for untold thousands. Thou hast outlived thy usefulness…”

This final goodbye could have been applied to each of our town’s grist mills as they closed down. In the years ahead, with the rapid development of electric vehicles, our town’s gas stations may eventually go the route of those long-ago grist mills.