Awe: The Pyramids of Pharaoh Sneferu induce wonder as they stand in splendid isolation above the desert sands

The pyramids on the Giza plateau west of Cairo are almost certainly the prime attraction for visitors to Egypt and they may draw thousands a day during the height of tourist season.

Relics of Egypt’s Old Kingdom rising starkly out of the desert, they overwhelm the visitor with their gigantic profiles. Though the 4,600-year-old Great Pyramid of Pharaoh Khufu is the most famous and towers nearly 450 feet, its neighbors belonging respectively to Pharaohs Khafre and Menkaure are stunning in their own ways. That of Khufu’s son Khafre is only a few feet lower than the Great Pyramid and, while Menkaure’s pyramid is only half the size of the other two, it projects its own grandeur.

These structures are massive, built of millions of limestone blocks weighing many tons and inspiring numerous theories — some remarkably daft — as to how they were constructed.

Perhaps the most outlandish is that they were built under the direction of alien beings who, having solved the challenge of faster-than-light travel, crossed many vast stretches of space for the purpose of showing less technically accomplished people how to pile up rocks. Might they not more profitably have taught them about electricity, computers, and advanced medicine?

Then there are those who insist that the three Giza pyramids are for some esoteric purpose lined up in a row like the stars in the belt of the constellation Orion — blithely ignoring the fact that any three objects in a row are arranged like the stars in the belt of Orion.

Nonetheless, there remain many questions as to how the ancient Egyptians raised the blocks in the pyramids to such great heights; how they managed to organize, feed, and house the required workforce; and what the impulse was to raise such monuments so that their kings might enjoy eternal life with their gods.

The fact remains, however, that there are many, many more pyramids on the west bank of the Nile River — they may number as many as 100 — some older than the Giza pyramids, some nearly as large, some eroded to heaps of rubble resembling natural rocky outcrops in the desert. They vividly show the evolution, the flourishing, and the final dissolution of the technology that raised them.

And contrary to popular depictions — Cecil B. DeMille notwithstanding — these structures were not built by slave labor. The graves of the men who raised them have been found and their remains are those of workers who not only enjoyed healthy diets but were given the best medical treatment available for injuries.

They frequently left behind graffiti on the blocks with which they were building indicating that they worked in teams that were in competition with one another, perhaps vying for extra portions of beer or time off.

But for all of their grandeur, it must be admitted that seeing the Giza pyramids at the height of tourist season as I did recently when they are surrounded by enormous noisy crowds posing for photos, bargaining with souvenir sellers or camel drivers for rides, or lining up in chattering groups for the chance to enter the pyramids’ eerie interiors can induce a negative reaction. Tourist brochures that show the pyramids seeming to be in isolation in the desert with nary a soul in sight are wildly misleading.

Pharaoh Sneferu’s pyramids

But a couple of dozen miles south of Giza on a lonely stretch of the great limestone plateau called Dashur rise the pyramids of Pharaoh Sneferu — well, two of them anyway — and they illustrate a remarkable chapter in the history of pyramid construction.

Sneferu was the father of Khufu and his building activities not only seem to have inspired his son to outdo him, they created a construction force that accomplished astonishing —sometimes bewildering — things and made possible the wonders of the gigantic pyramids of Giza.

But the story of Sneferu’s pyramids begins about 20 miles from Dashur on a site with a spectacular view of the Nile River where Sneferu ordered the construction of what is now known as the Pyramid of Meydum (or Meidum). Googling the name and clicking “images” reveals a structure that looks like a tower rising above the desert — all that remains of Pharaoh Sneferu’s initial bid for immortality.

And that was precisely the function of pyramids — they are what archaeologists term “resurrection machines”: Pyramids were intended to carry the deceased pharaoh to the realm of the Sun-god Ra. For generations before Sneferu, pharaohs built what are called today “step pyramids,” looking like huge staircases reaching toward the sky.

But perhaps inspired by shafts of sunlight breaking through clouds and forming wedge shapes on the horizon, Sneferu commanded his architects and engineers to try something new.

After what must have involved years of planning and construction, something went wildly wrong. Whether the ground beneath the pyramid was too soft to bear its weight or there was some major engineering error as the structure grew in mass, a catastrophic collapse occurred and much of the pyramid was reduced to a pile of rubble on which its interior structure sits today.

Interestingly, the intended burial chamber and the passages leading to it survived the collapse. But Pharaoh Sneferu was not about to start his journey to the afterlife in this monumental failure so he ordered his engineers and work teams to start a new pyramid, this one in the site called Dashur.

No one knows how much time and treasure was lost in the building of the Meidum pyramid — the ancient Egyptians did not keep records of such endeavors — but Sneferu’s subjects dutifully regrouped and went to work. One does not question the will of a god-king.

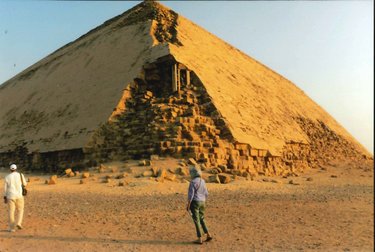

The result of their efforts stands today above the bleak sands of Dashur — the strange construction known as “the Bent Pyramid”-- (Figure 1) 600 feet on a side and towering 330 feet above the Sahara, the enormous structure is visible from many miles away.

But its odd shape demonstrates that Sneferu’s engineers had not yet fully learned from their failure at Meidum. As the pyramid grew in elevation, cracks began to appear in its base threatening collapse.

The slope of the pyramid was evidently too steep and had exceeded the angle of repose, meaning that the whole thing could collapse as had the pyramid of Meidum. To solve the problem, they changed the angle of the sides, thereby reducing its final weight and resulting in the “bent” profile the pyramid exhibits today, though the separation of some of the lower sections of the structure show the effects of the steep angle.

The interior of the pyramid was also completed — a complex series of tunnels and rooms leading to an impressive burial chamber with a corbelled ceiling. The fact that these are intact after over 4,600 years shows that Sneferu could indeed have agreed to be interred there.

But incredibly the pharaoh appears to have said something like, “Very nice but not what I ordered up. Let’s try again.”

It is at this point that two relevant facts should be mentioned. The first is that there is a small step pyramid on a site called Seila near Egypt’s fertile Fayum area, which also apparently was built at Sneferu’s command though its interior was evidently never intended for a burial.

The other fact is that, for generations after his reign, the pharaoh was referred to as “Good King Sneferu” and had the reputation of kindness and generosity toward his subjects. What these folks thought about all that labor and national treasure going into the building of Pyramid Number Four is unrecorded.

Known today as “the Red Pyramid,” the giant structure rises about a mile to the north of the Bent Pyramid and it is a masterpiece. Third in size to the Giza pyramids of Khufu and Khafre, it gets its name from the presence of oxidized iron in the limestone blocks from which it was constructed, a coloring that time has intensified.

Its somewhat flattened appearance demonstrates that Sneferu’s engineers had learned from their past errors and gave the pyramid a more stable profile, enduring through the millennia without obvious signs of erosion. Neither Sneferu’s son Khufu nor any subsequent pharaohs in Egypt’s Old Kingdom attempted a pyramid with sides as steep as those of the Bent Pyramid.

Today these monuments induce wonder as they stand in splendid isolation above the desert sands. They are seldom visited. The day my companions and I went to Dashur, there were just three other people at the Bent Pyramid. At the Red Pyramid, there were none.

Yet here rise two of the master works from Egypt’s past proclaiming the ingenuity of their builders and perhaps the ego of their pharaoh. Lacking the sometimes carnival atmosphere that accompanies the Giza pyramids, they silently evoke the mystery and stimulate the contemplation for which they surely were intended.