New Mexico’s ‘tent rocks’— a geologic wonderland

A point I have always tried to make with my students or participants in one of my field trips is that geologists have a name for absolutely every natural process involving the rocky sphere that is Planet Earth. And one of the wonderful things that has happened in recent decades is that scientists have sent robot probes to examine the surfaces of other planets, as well as asteroids and comets, and have found not only that many of the same processes occur on worlds as alien as the Moon, Venus, and Mars, but have discovered exciting evidence of other geologic phenomena unknown on Earth and waiting to be explained.

Over the past few days, the Internet has been sizzling with reactions to a rock photographed by the Curiosity Rover that has a passing resemblance to a thighbone. Given the fact that not one of the robots sent there has yet found persuasive evidence that anything as large as a microbe ever lived on Mars, the curiously shaped rock is unlikely to be anything but that: a curiously shaped rock.

But the various chat rooms that dwell on such things are buzzing with charges that NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration) is once again concealing evidence of macrobiotic life on Mars and those who disagree are denounced in vitriolic (and often hilariously ungrammatical) language.

Yet the fact is that the natural processes which change the shape of Earth’s surface are sometimes capable of producing very curious results: hence, the chess-piece shapes of the rocky towers of Bryce Canyon, the elegantly sculptured mesas and buttes of Monument Valley, and the granite profile of New Hampshire’s Old Man of the Mountains that collapsed ignominiously some years ago into a heap of rubble due to frost-wedging.

A few weeks back, on emerging from a trip with some students through one of the caves near the village of Clarksville, I noticed some odd, miniscule features on a pile of muddy debris at the cave’s entrance. The debris was glacial drift, deposited on the Clarksville area by one of the streams pouring off the melting Ice Age glaciers thousands of years ago: hundreds of penny-sized and smaller pebbles in a matrix of packed clay.

But many of the pebbles stood atop a small, thin column of that clay, forming tiny structures geologists call by the French term “damoiselles”— which loosely translates as “little maidens.” Evidently, to the French-speaking geologists who coined the name, the pebbles resembled broad bonnets perched atop the slender structures below.

This happens when rain water or melting snow cascades down an exposure of soft sediment, washing away anything that is not protected by the tiny pebbles; their weight has slightly compressed and hardened the materials on which they sit.

In many places in the world, these structures appear on a much larger scale. Chimney Bluffs State Park on Lake Ontario features enormous examples, which are often given the name “hoodoos” when they form such massive structures. A somewhat smaller display of hoodoos appears on the mysteriously named “Ghost Fire Bend” of the Normanskill, though these are currently not accessible by car with the closing of Grant Hill Road due to road work.

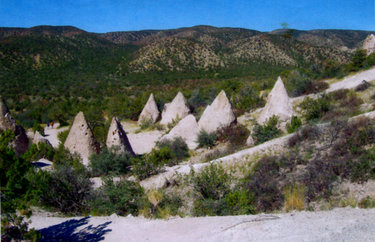

In June of this year, while on a hiking trip to New Mexico, I had the opportunity to visit Tent Rocks State Park on the reservation of the Cochiti Pueblo, southwest of Santa Fe. The preserve was originally given the Keresan language name Kasha-Katuwe, which is usually translated as “rocks that resemble teepees.”

Here, between 6 million and 7 million years ago, the land was buried under the debris from an incredibly violent volcanic eruption that formed the Jemez Caldera, a giant bowl-shaped depression to the north. Layers of the soft, spongy-looking rock known as pumice, compacted rock fragments called tuff, and volcanic ash buried the region in layers hundreds of feet thick.

The weight of all of that air-borne sediment compacted the strata into a crumbly matrix rock that weathers easily due to the wildly varying seasonal temperatures and is poorly resistant to erosion by the occasional rainfall or melting snow. But mixed in with the smaller rock fragments are boulders, some the size of an automobile, and these had the effect of compressing and compacting the sediments that lay beneath them. Thus the sediments were protected from the raging, highly erosive waters that flow during those occasional periods in arid climates when sudden torrential rains fall.

The results are the hoodoos of Kasha-Katuwe, and they are marvels to behold.

Those found near the parking area for the preserve’s trailheads gave Tent Rocks its name. There are a dozen or more of them, ranging in height from a couple of yards to 20 or 30 feet, but these represent the last stage in the erosion cycle of the hoodoos. They have lost their protective boulder caps and, in respect to geologic time, they are not long for this world.

Though this part of the Southwest is currently experiencing a severe decade-long drought, every drop of rain that does fall is washing them down to ground level, the eventual fate of all hoodoos.

To get a better idea of nature’s inventive sculpting talents, one must hike up one of the two major trails that head into the park. They are easy for the experienced hiker, though the lack of shade and the unforgiving summer sun make it mandatory to carry a couple of quarts of water. In addition, signs warn of poisonous snakes lurking in the underbrush — sufficient cause for those inclined to bushwhack to stay on trail.

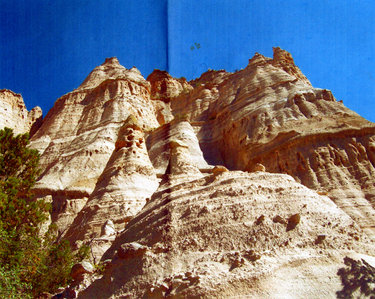

A textbook example of the formation of the hoodoos lies on the edge of the eroding mesa around which the trail meanders. Rising some 20 feet from the middle of a dry wash, the structure is crowned by a large boulder of pumice.

Farther along the trail, the hoodoos become larger and more varied in shape and one particularly steep slope offers a view of their entire life cycle: some eroded down to mere stubs, some proudly displaying their protective caps, and others just beginning to emerge from the eroding cliffs.

They derive their weird shapes from the varying hardness of the rock strata from that they form. A slot canyon cut into the rock by raging waters offers a shady respite from the heat and climaxes in a hair-raisingly steep and exposed series of switchbacks leading to a jaw-dropping view out over the canyon to Sandia Mountain above Albuquerque.

The American Southwest — particularly in New Mexico and Arizona — features some spectacular geology due to its diverse rock types; its wildly varying elevations; and its climate, which tends to be arid but is subject to sudden intense flooding.

Terms such as “weathering,” “erosion,” “resistance,” “strata,” “frost wedging,” and other prosaic expressions may seem lifeless on the page of the textbook. But, in an environment such as Tent Rocks State Park, these dry words describe nature’s endlessly varied talent to create wonders in the rock from which Earth is made.