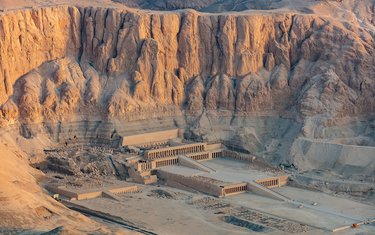

Awe: A temple for the woman who would be pharaoh

— Photo by Diego Delso, delso.photo, license CC-BY-SA

Known in ancient times as “Djeser Djeseru” — “the holy of holies” — the great temple of Pharaoh Hatshepsut is the work of Senenmut, her architect and consort.

It appears in the desert like a shimmering mirage — appropriately, as temperatures here can rise to 125 degrees Fahrenheit. At the base of the mountains west of the Egyptian city of Luxor in an embayment called Deir el-Bahari sits the temple known in ancient days as Djeser Djeseru — “the holy of holies.”

It was constructed at the command of a royal woman named Hatshepsut under the direction of Senenmut, her architect, and is like no other building in Egypt. With its polished limestone pillars reflecting the blazing sun punctuated by dark spaces that draw the eye inwards to the temple’s dark recesses, its design seems to mirror the cliffs above it with their vertical faults and fractures and the shadowy spaces within them.

Though it is three and a half millennia old, it appears modern. Its design and setting evoke awe and its history contains some of the greatest mysteries that have come down from ancient Egypt.

Near the beginning of Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty, around 1500 B.C., the country was ruled by a pharaoh named Thutmose II. The word “pharaoh” comes from the Egyptian word “pero” meaning “great house,” and was applied to the kings much as we use today the expression “the White House” to refer to the president.

Thutmose II was married to the royal woman Hatshepsut who may have been his half-sister. (Such relationships were not uncommon among Egyptian royalty.) By her, he had two daughters but no sons and, when he died at an early age, the next in line was his nephew, Thutmose III, a small child who required a regent.

Usurpation

Hatshepsut was only too eager to fulfill the role and soon their images appeared side by side on monuments with inscriptions describing young Thutmose as pharaoh but stating that Hatshepsut “settled the affairs of Egypt.” In the words of Egyptologist Barbara Mertz, that statement must be one of history’s most tactful descriptions of usurpation.

Ancient Egyptian does not have a word for “queen,” as almost all of the rulers during the country’s 3,000-year history were male. The word sometimes translated as “queen” is the Egyptian expression “king’s great wife,” used to describe the pharaoh’s foremost spouse — pharaohs had many!

But before long Hatshepsut dropped her pretense of being the power behind young Thutmose and on monumental walls and in statuary had herself portrayed in the male garb of pharaohs, even to displaying the false beard they wore in ceremonies; on occasion, carvers even confusedly used the words “he” and “she” referring to her in the same inscription.

But since the language lacked a word for “queen,” she is often awkwardly described as “the (female) pharaoh.” Meanwhile, as young Thutmose grew older, he was being denied the throne that should have been his.

Hatshepsut proved herself a capable ruler, quelling rebellions in far parts of the country’s empire, sending trade expeditions to the exotic land of Punt on the east African coast, and building monuments and obelisks.

But one of the first mysteries that emerge is the question of how she persuaded other Egyptian royalty and the common people of the country to accept her role as pharaoh. One would think that such a stunning intrusion into the usual line of succession would have been earthshaking but from all evidence the years of her usurpation of the throne were peaceful and prosperous with time and resources available to build Djeser Djeseru.

Senenmut

How and when Senenmut came into the picture is another mystery. From the little that is known of his person it can be deduced that he was not of noble lineage. None of the few references to him that remain indicate nobility but since he was apparently a commoner one has to wonder from whence came his great talent as an architect and engineer.

He first appears as a tutor for Hatshepsut’s two daughters and, as he was obviously a frequent visitor to the royal quarters, one can imagine that he might have attempted to ingratiate himself with the widowed Hatshepsut — a “man on the make” in the words of Barbara Mertz.

In any case, the relationship that seems to have formed between the two — an aristocratic woman and a commoner — suggests a novel of D.H. Lawrence. The evidence for this pairing being more than Platonic first appeared when the interior of Djeser Djeseru was excavated.

In the dark recesses of the temple in areas apparently infrequently visited in ancient days were found inscriptions reading “Senenmut, the royal architect.” Such a bold intrusion into a temple intended to glorify a sitting pharaoh and dedicated to the goddess Hathor, patron of women, and Osiris, god of the dead, would no doubt have scandalized both the elite and common people of Egypt.

In rock quarries near the great temple have been found obscene graffiti depicting Hatshepsut and Senenmut in compromising positions.

Moreover, as Hatshepsut had workmen prepare a magnificent tomb for her in the Valley of the Kings — another intrusion into traditional male territory — she also had prepared for Senenmut an elegant resting place in the cliffs bordering Djeser Djeseru.

The tomb still exists in spite of the eventual fate of Hatshepsut and her consort. Its walls are covered in hieroglyphic prayers for the dead and its ceiling is painted with astronomical star charts and constellations, the meanings of which Egyptologists are still trying to decipher.

But this fact coupled with Senenmut’s talents as an architect and teacher suggest a true Renaissance man — an Egyptian Leonardo da Vinci.

Egypt’s Bonaparte

Two decades into her reign, Hatshepsut disappears from history. Whether she died or was overthrown by her young nephew Thutmose is unknown but he finally ascended the throne and became one of Egypt’s most powerful rulers, conquering new territories and earning a reputation today among scholars as Egypt’s Napoleon Bonaparte.

What we do know is that 20 years into his reign he began a campaign to obliterate his aunt’s presence from Egypt’s often propagandistic history and Hatshepsut was removed from the list of kings, making young Thutmose appear to be the direct successor to Thutmose II.

Her name was erased from many of her monuments — even in Djeser Djeseru. Lofty obelisks proclaiming her greatness were covered in plaster or surrounded by casings that hid references to her.

Colossal statues of her carved from hard Aswan granite were smashed to pieces and buried in the rubble in the slopes surrounding her great temple.

Most ominously, two almost identical beautifully carved granite sarcophagi intended for the mummies of Hatshepsut and Senenmut were also reduced to fragments — evidence of fury directed beyond the grave.

And yet another mystery arises: If young Thutmose was filled with such hatred directed at Hatshepsut and Senenmut, why did he wait 20 years to unleash his wrath?

Of course, Thutmose III eventually went to his elaborate tomb in the Valley of the Kings and his name is likely known only to the Egyptologists who labor in the dusty deserts of Egypt, retrieving the remnants of that ancient civilization’s wonders.

But most every visitor to Egypt today visits the Valley of the Kings and Djeser Djeseru. Mention Hatshepsut or Senenmut and one of the guides who haunt the temple will rush forward to regale you with stories of the two, some of them — needless to say — salacious.

But the ancients had a saying: “To speak the name of the dead is to make them live again.”

In the awe induced by the splendor of Djeser Djeseru, the woman who would be pharaoh and her architect lover do indeed walk the Earth again.